British actor Christian Bale plays Moses in Ridley Scott’s new film Exodus: Gods and Kings, which opens next Friday. Aussie Joel Edgerton (Ramses II) and Idahoan Aaron Paul (Joshua) also star. In response to criticism of the mostly white cast, media mogul Rupert Murdoch tweeted: “Since when are Egyptians not white? All I know are.” What was the skin color of ancient Egyptians?

Not white. There is not yet enough evidence to make a definitive judgment about the pigmentation of the pharaohs or Moses, who himself was likely an Egyptian. Mummies are too desiccated to reveal skin tone, and the tiny amount of genetic evidence they have yielded so far adds nothing to the question. As the Explainer wrote back in 2011, small differences in bone structure don’t reliably indicate the race of a recently deceased person, let alone a 3,000-year-old corpse. We are mostly limited to the subjective statements of Egyptians and the outsiders who depicted them, which suggest that majority of people of pharaonic Egypt were neither white nor black, by modern standards.

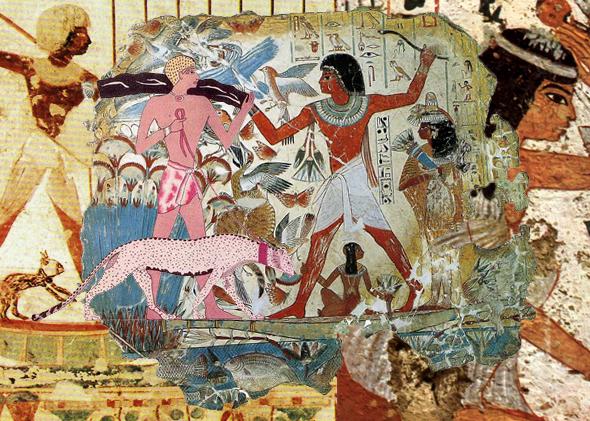

Herodotus, for example, referred to the Egyptians as melanchroes. That term is sometimes translated as “black-skinned,” but Herodotus typically used a different word to describe people from further south in Africa, suggesting that “dark-skinned” is more appropriate. He also compared Egyptian skin to that of the people of Colchis, in the Southern Caucasus. The Egyptians typically painted representations of themselves with light brown skin, somewhere between the fair-skinned people of the Levant and the darker Nubian people to the south. These paintings, however, may not be entirely reliable, because Egyptian artists didn’t always faithfully attempt to recreate reality. They sometimes alternated skin tones of people in a row to create contrast. Men were depicted with darker skin than women to represent gender roles—men worked in the fields while women stayed in the home—even when the subjects were royalty who did not engage in manual labor.

Were Egyptians white?

Photo illustration by Ellie Skrzat. Photos by Eberhard Dziobek, Unknown, Marcus Cyron/British Museum, and Maler der Grabkammer der Bildhauer Nebamun und Ipuki/The Yorck Project. All photos via Wikimedia Commons.

Ancient Egypt was a racially diverse place, because the Nile River drew people from all over the region. Egyptian writings do not suggest that the people of that era had a preoccupation with skin color. Those who obeyed the king, spoke the language, and worshipped the proper gods were considered Egyptian. Outsiders were allowed to marry Egyptians. Even the aristocracy was racially integrated. Princesses from the Levant joined the Egyptian nobility. Maiherpri, a dark-skinned Nubian who lived shortly before the reign of Ramses II, was also part of the Egyptian royal court and was buried in the Valley of the Kings.

The skin color of ancient Egyptians is a long-running modern debate, both among scholars and in the lay community, even if the ancient Egyptians themselves didn’t much care about it. The last major flare-up came in 2005, when National Geographic launched a traveling exhibition featuring a reconstruction of the face of the boy-king Tutankhamun. A pair of earlier representations had suggested darker skin, and the lighter National Geographic version annoyed some observers. The Franklin Institute in Philadelphia convened a conference at which scholars slammed the depiction as too white. (One participant even compared the bust to a young Barbra Streisand.)* Nearly a decade later, though, the light-brown depiction of King Tut remains as good a guess as any.

Explainer thanks Emily Teeter of the University of Chicago.

*Correction, Dec. 3, 2014: This article originally misspelled Barbra Streisand’s first name.