“It feels like the slime is after me personally,” says Dr. Erin Gilbert in the reboot of Ghostbusters. The running joke here is that Kristen Wiig’s character is the uptight member of the team, and she’s the one who’s always getting smeared with goo. The slime, though, has little more than a walk-on role in the new movie, the equivalent of the cameos handed out to cast members from the original films. One gets the sense it’s there to please the parents in the crowd.

When the original Ghostbusters came out in 1984, earning $300 million at the box office, green ectoplasm was its breakout star. In the years that followed, slime took over at the multiplex, dominated television, and spilled out into supermarket aisles, toy stores, and arena rock shows. It oozed into the mainstream and remained on top for half a decade. Then, as quickly as it came to us, prime slime time slipped away. Whither all that goo?

The five-year stretch from 1984 to 1989, from Ghostbusters to Ghostbusters 2, was the slimiest in American history. The stuff had been around before—Dr. Seuss once called it oobleck—but only then, in the middle of the 1980s, as the Cold War reached its anxious end, did slime spread far and wide.

The ur-slime was Urschleim: the original mucus, an amoeboid living ooze, dredged up from the bottom of the North Atlantic by the steamship Porcupine in 1868. Biologist Thomas Huxley linked this murky sludge to the “little floating globules of slime,” or “organisms without organs,” that German scientist Ernst Haeckel had first observed, several years before, in the French Riviera. Now he suggested that the slime was a formless protoplasm—the common and primeval source of every living thing, laid out in a slimy, living blanket on the ocean floor. Huxley would later admit that he was wrong about the deep-sea muck, but many 19th-century biologists thought that plasm was the stuff of life. According to this view (widespread before we knew about nucleic acids), the jelly that’s contained inside each cell might encode heredity in the form of jiggly vibrations. Or, as Gilbert and Sullivan would put it in 1885: “I can trace my ancestry back to a protoplasmal primordial atomic globule; consequently my family pride is something inconceivable.”

From there it wasn’t such a leap to guess that protoplasm might, in certain extraordinary moments, coalesce and be projected from the body. Thus the ectoplasm, or exterior slime, that spilled across the table during a psychic spell or séance and eventually showed up in Ghostbusters. At the turn of the 20th century, researchers of great renown studied this alleged goo, in what Arthur Conan Doyle would describe as “a separate science of the future which may well be called Plasmology.”

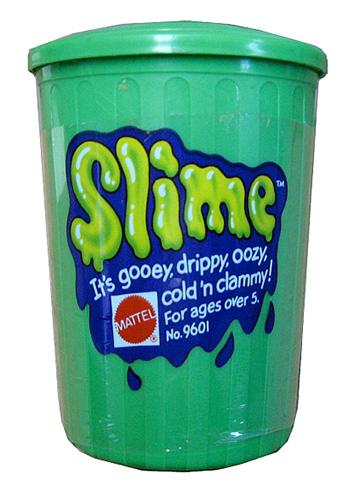

That is to say, the phenomenon of slime, even paranormal slime, would be for many years both serious and scientific. But biology moved on from protoplasmic theory, and slime itself began to seem absurd. By the 1940s, it had gotten Seussian and silly. As Slate staff writer Rebecca Onion explains in her essential essay for the Atlantic, ooze appealed and still appeals to children on account of its being gross: They like the fact that grown-ups find it so disgusting. Indeed, that market would be tapped in 1977, when the Mattel toy company, in search of a product to compete with Play-Doh, came up with a sleeper hit: little, plastic garbage cans of gel called Slime. (Tagline: “Gooey, drippy, oozy, cold ‘n clammy.”)

Screenshot via The Pop Top Shop

“We brought in children to the test facility, to see how they would play with it,” says Octavia Miles, who served as Mattel’s product manager for Slime. Miles, who’s now in her early 80s, worked on many other toys, including Hot Wheels. But she still remembers the first time she saw kids play with Slime in focus groups: “They threw it at each other, they pulled it, they smelled it, they tasted it, they ran it through their hands,” she says. “Oh, the excitement on their faces when they opened up their cans! One little boy emptied the whole can on the floor and started jumping up and down on it.”

Slime hit shelves in April 1977 and turned out to be the year’s best-selling toy, at 11 million units. Jane Pauley played with it on Today. Forty tons of Slime were shipped to stores in England. Copycats tried to steal its market share. (Soon kids could buy even cheaper plastic cans of “Yuk,” which was promoted with the slogan “silly-chilly, ooey-gooey, glows in the dark.”)

Miles and her team did their best to double down on Slime’s success. In 1978, they put out a new variety with plastic worms inside, but kids never cottoned to the recipe. “I think many people were rather revolted by the worms,” she says. Or maybe Mattel had made a different error: The company switched the goo from green to pink. Sales began to falter.

Branded Slime would disappear, but kiddie ooze stayed popular and made its way onto TV. According to Mathew Klickstein, author of Slimed: An Oral History of Nickelodeon’s Golden Age, the network’s famous slime first appeared on a weird, anarchic show from Canada called You Can’t Do That on Television, in one of its very first episodes from 1979. They hadn’t yet worked out a recipe, so the original sliming entailed a bucket of real-life, moldy food slop, dumped onto a child’s head. (“It made people’s eyes water on set, it smelled so terrible,” Klickstein says.) When kids wrote in to say how much they loved the gag, the show’s producers gave them more and more.

A few years later, Nickelodeon brought You Can’t Do That on Television to the U.S. and green goop became the channel’s major selling point (and the basis for its slime-soaked game show Double Dare). It was “a symbol of the demarcation between grown-ups and kids,” one network executive said. According to Klickstein, the slimings made the kids on Nickelodeon more relatable. “You’re coming home from school and you’ve been shit on all day,” he says, “and then you see kids on TV get shit on, and that connects you to them.”

Meanwhile, another, darker strand of slime culture had started to emerge from the 1970s underground. This was protest slime, counterculture slime, Frank Zappa singing “I’m the Slime.” Green sludge came to represent the effluence of government and industry—toxic waste as literal and figurative pollution. (Zappa: “Have you guessed me yet? I am the slime oozing out from your TV set.”) Environmental activists took on the fight against oppressive slime, leaking from the nation’s power plants and its atomic arsenal.

As an icon of this nuclear threat, the canister of glowing slime grew more salient as the decade reached its end. In 1979, a nuclear reactor melted down in Pennsylvania—less than two weeks after the release of The China Syndrome, a Jane Fonda eco-thriller about the risk of just such an accident. A documentary film about the meltdown described it using “terms that are nearly biblical,” according to a contemporaneous New York Times review, “speaking of dying livestock, scorched trees, mysterious skin rashes and a strange metallic taste everywhere.” (In the wake of the disaster, Mad magazine even changed its famous motto from “What, Me Worry?” to “Yes … Me Worry.”)

Nuclear terror mounted. The anti-nuclear protest movement swelled. In 1982, close to a million people rallied for disarmament in New York City’s Central Park. “It’s not just hippies and crazies anymore,” one activist claimed, “it’s everybody.” The following spring, Ronald Reagan declared the Soviet Union “an evil empire” and warned the peaceniks it would be a grave mistake “to simply call the arms race a giant misunderstanding.” (A few weeks later he announced the creation of the Strategic Defense Initiative, a missile-defense system that seemed sure to provoke a Soviet response.) Then in November, ABC aired The Day After, a terrifying TV movie that depicted nuclear holocaust on U.S. soil, with mushroom clouds and people being vaporized. About 100 million people watched. (Rebecca Onion has another excellent essay on how this film affected kids.)

Protest slime reached its peak in 1984, the annus mirabilis of ooze. In May of that year, Lloyd Kaufman, of the indie-film studio Troma Entertainment, put out an ultra-violent cult classic called The Toxic Avenger, about a nerd who falls into a vat of radioactive green slime and turns into a deformed superhero. The movie starts with a voice-over and a shot of the New York City skyline: “For all this industrial advancement, there is a price to pay: pollution. The unavoidable byproduct of today’s society.” It ends with Toxie, now the champion of the downtrodden and the working class, disemboweling the corrupt mayor of the town. “Officer,” he says, pointing to the mayor’s corpse, “take care of this toxic waste.”

The Toxic Avenger was meant to be a film about the evils of pollution and the “the three elites,” Kaufman told me in an interview: the labor elite, the bureaucratic elite, and the corporate elite. Why green slime in particular? That came from the Eastern philosophy that Kaufman studied as an undergrad at Yale University. “I thought of it in terms of the yin and the yang,” he says. “You know, the oyster gets a piece of sand stuck in its asshole and it’s very painful, but it produces a beautiful pearl. I tend to do things the opposite. … So I said, let’s make green the color of pollution, the color of contamination, the color of corruption.” (He has another, less highfalutin explanation for the color: When it came to bodily fluids, the motion pictures rating board was very strict about the color red. Put in too much blood and you’d be sure to get an X rating.)

If we were being strictly scientific, we might conclude that nuclear waste should be colored blue. But with due respect to Kaufman’s yin and yang, slime was colored green before The Toxic Avenger. In Modern Problems, a comedy from 1981, Chevy Chase plays a loser who gets doused in radioactive ooze. He turns green and develops magic powers. In an episode of Diff’rent Strokes from 1982, Kimberly washes her hair using water tainted with acid rain. Her hair turns green and she’s embarrassed. The link between toxicity and the color green goes back at least to the 19th century, when a brilliant emerald dye made with arsenic became the rage in fashion and interior design. Then, in the 1910s, the U.S. Radium Corporation started manufacturing glowing-green, radioactive paint. (That stuff was made in Orange, New Jersey—not so far from Toxie’s hometown.)

In any case, I don’t think it’s fair to say that toxic-green pollution, as embodied in the canister of slime, represents the opposite of nature; rather, it’s more like its twisted sister. The color—not forest green but uncanny neon—is much too bright to be organic, yet close enough to a real-life hue to seem perverse.

Slime stood in for weirdness and mutation of the status quo. It gave power to the freaks. In the first issue of the Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles comic book, also from the spring of 1984, a strange canister of glowing ooze spills onto the turtles and transforms them into superheroes like Toxie. This trope mirrored, in its nerdy way, another form of early 1980s slime: punk rock’s subversive, slimeball chic. With their ripped-up clothes and dresses made from trash bags, punks made themselves a community of misfits, wallowing in slime. (Among the era’s punk and hardcore bands: Slime, Biohazard, Toxic Waste.)

In the summer of 1984, with all this as the backdrop, Ghostbusters splattered slime into mainstream culture.

At first glance, the movie seemed to peddle the classic, gooey tale of ectoplasmic underdogs. Like Toxie, the Ghostbusters went up against the jerks in City Hall as they tried to clean up their community. They were the misfit populists, getting slimed by the elites (and an adorable glowing green blob). But taken in the context of the time, amid the growing anti-nuclear movement, the message of Ghostbusters couldn’t be clearer: It’s on the side of Ronald Reagan.

The film’s politics plays out in its slime. The ectoplasm in Ghostbusters does not derive from the government and industry, as it does in The Toxic Avenger. Rather, it marks the footprints of invading ghosts—an imperialist army overseen by an evil, foreign dictator. To battle these intruders, and cleanse the world of slime, the Ghostbusters must deploy their proton packs, or as Peter Venkman (Bill Murray) calls them, their “unlicensed nuclear accelerators.”

Unlicensed, indeed. Who’s the human villain in the film? It’s Walter Peck, an inspector from the Environmental Protection Agency. He’s the one who tries to get the Ghostbusters shut down, telling them they face federal prosecution for “at least half a dozen environmental violations.” While the innovative, small-business-owning, capitalist heroes try to save the world, that damned Peck tries to thwart them with his rules and regulations. Eventually he succeeds in shutting off their power and in so doing releases all the paranormal slime they’d safely stowed away. It nearly destroys New York City.

You don’t need a Ph.D. in oozology to get the lesson here: Faced with an existential threat to human life, nuclear weapons are the answer—and don’t let any wuss environmentalists tell you otherwise (not even if there are a million of them rallying in Central Park). This latter point is spelled out explicitly: The anti-nuclear activists are a bunch of sissies: “Yes, it’s true,” Venkman tells the mayor, gesturing at Peck, “this man has no dick.” (I remember that line from when I first saw Ghostbusters in the theater. It killed.)

In the wake of this emasculation, the mayor sends the Ghostbusters back out to save the city—and agrees to overlook any possible infringements of the Environmental Protection Act. Our heroes then risk disaster by “crossing the steams” of their proton guns as a means of killing the evil Gozer. Their plan works, and their nuclear weapon finds it target. Gozer bursts into a mushroom cloud of goo. Everybody cheers. The end.

And with that, slime became a massive hit.

A few years ago, I looked into the history of quicksand—another goop that splashed into pop culture for a while, then all but disappeared. I learned how movie quicksand came to represent the confusion and uncertainty of the 1960s, a time when the earth seemed to shift beneath our feet. Slime also started out that way, as the expression of a deeply held anxiety. It symbolized the noxious overflow of our Cold War terror—something gross and powerful, at times so scary that it made us laugh.

At its peak in 1984, slime’s darker meanings melted into marketing. Ghostbusters, with its goofy, reactionary plot, stripped the ooze of its significance. It made radioactive waste into a silly sludge, more Mattel than Zappa, and one that could be rebranded with greater ease as “nontoxic” merchandise for kids. Slime had been for sale before, of course, but now it reached its full potential.

Slime-inspired gross-out toys dominated the marketplace in 1985. Think of Stinkor, the foul-smelling He-Man action figure made with patchouli oil. Or the immensely popular Garbage Pail Kids, a yucky riff on Cabbage Patch, with names like Slimy Sam, Oozy Suzy, Meltin’ Melissa, and Adam Bomb. In the 1987 movie version, the Garbage Pail Kids are born from a trashcan full of green slime.

According to one newspaper story from 1986, even the makers of the Care Bears and Strawberry Shortcake caved in to Generation Slime. The company started manufacturing a series of rubber balls made to look like faces, with “exposed brains, cracked skulls, and dislodged eyeballs.” That same article goes on to quote a child psychologist on the “yuck stage” of development. “Playing with these toys is quite healthy for children,” she said, “because it helps them control their fears.” That’s what slime became: a salve for nuclear worry, nuclear waste refigured as a poop joke.

As kiddie gross-out slime went supernova, a run of mini-budget, melty horror flicks followed in the slime-trail left by The Toxic Avenger. See, for example, the white slime of The Stuff (1985); the dark and sticky slime monster in Kaufman’s follow-up, The Class of Nuke ’Em High (1986); the purple melting hobos in Street Trash (1987); or the mustard-yellow zombie goo of Slime City (1988). This gooey strand of lowbrow cinema didn’t want to impart a lesson. These gross-outs existed purely for the sake of grossing people out.

As the slime trend softened and expanded, a new and countervailing force began to rein it in: glasnost. The Cold War’s final phase meant the end of slime’s ascendance. At the end of 1987, Reagan and Mikhail Gorbachev signed a major treaty to disarm. One year after that, Gorbachev pledged a new phase of “de-ideologized” international relations, where nations could be free of outside interference. By the time Ghostbusters 2 arrived, in June of 1989, the Berlin Wall was only months away from coming down.

Harold Ramis and Dan Aykroyd, the movies’ writers and co-stars, understood that slime had changed and would have to play a different role. “Slime is our metaphor for the human condition,” Ramis ventured to the New York Times when the second film was in production. In the end, they recast the slime as a pink and purple river, a 25,000-gallon reservoir of ooze coursing underneath the city. Before, the ectoplasm signified something alien that must be beaten back; now, it flowed from New Yorkers themselves. “All of the bad feelings, you know, the hate, anger, and the vibes of the city are turning into this sludge,” Winston tells the mayor. “Isn’t it interesting how the slime has taken on sort of a personality of its own,” noted Oprah Winfrey on her show, as she dipped her hand into the stuff.

This time around the Ghostbusters’ nukes would be useless. When they shoot the slime with their proton packs, the beams have no effect. They need something else to erase the glasnost-era slime: the power of positive thinking. Not long before the first film was released, Reagan had warned against the “soothing tones of brotherhood and peace,” that these were just the sneaky tools of the aggressor. Now Ghostbusters 2 reversed that formulation: To fix the world, the movie says, we must rely on comity and good intentions.

In the sequel’s dopey, final scene, the heroes use happy vibes to animate the Statue of Liberty, then maneuver her to punch her freedom-loving fist through the shell of slime. It’s New Year’s Eve. Love and friendship have been restored. The crowd sings “Auld Lang Syne.”

Was that the end of slime? It didn’t go away completely—one still finds oozy, yucky toys on sale and green goop on certain shows for kids. (Kobe Bryant got slimed on Nickelodeon last week.) But I’d submit that 21st-century slime is just a trickle of its former self. The marketers for the Ghostbusters remake will try to sell us slime again: in slime-filled Twinkies, for example, or rebooted ecto-flavored green Hi-C. But slime may simply be too slow and viscous for the modern world. Worries over toxic sludge have given way to fears of greenhouse vapor. The Cold War’s steady drip of dread has condensed into a fog of panic over terrorism. And no one really talks, as Frank Zappa once did, about the ooze that comes out of our TV sets. That sort of slime, the slime of corporate mind control, now seems to hit us from the cloud. In a faster, more connected world, our nervousness has gotten nebulous—and slime seems pretty safe.