This story is republished with permission as part of the Climate Desk collaboration.

A lot of Champagne was popped on the night of Dec. 12, when diplomats from almost every country on Earth finalized the text of the historic global agreement to combat climate change. In the Paris Agreement, countries committed to hold global temperature increases to “well below” 2 degrees Celsius (3.6 degrees Fahrenheit) above preindustrial levels, an ambitious target considering that the world is already more than halfway to that limit. The deal also laid out a system for wealthier nations to help poorer ones pay for adapting to unavoidable climate impacts.

But finalizing the agreement was only one step on the long road to actually achieving its aims. The next step is happening Friday, on Earth Day, as heads of state and other top officials from more than 150 countries will gather at the United Nations headquarters in New York City to put their signatures on the deal. Secretary of State John Kerry, who was a driving force in Paris, will sign the document on behalf of the United States.

Signing the document is mostly a symbolic step, indicating a country’s intent to formally “join” the agreement at some later stage. In order to “join” the agreement, national governments have to show the U.N. the piece of domestic paperwork—a law, executive order, or some other legal document—in which the government consents to be bound by the terms of the agreement. Some small countries, including some island states that are among the most vulnerable to climate impacts, are expected to offer up those documents at the same time they sign. Other countries will take longer. The agreement doesn’t take legal effect until it is formally joined by both 55 individual countries and by enough countries to cover 55 percent of global greenhouse gas emissions (a threshold that essentially mandates the participation of the U.S. and China).

The World Resources Institute made a pretty cool widget for experimenting with various ways to reach those thresholds. You can play around with different options to see what it would take. Once countries start signing the agreement, the widget will automatically update accordingly:

President Barack Obama and Chinese President Xi Jinping have promised to join the agreement this year. Obama is expected to join using an executive agreement, which will allow him to avoid sending the deal to Congress. (Executive agreements account for the vast majority of U.S. foreign commitments.) He’s able to do this because the U.S. says it can fulfill its Paris promises without any changes to domestic laws; instead, the Obama administration is holding up its end of the bargain by imposing new Environmental Protection Agency regulations on emissions from power plants.

Unlike a treaty, an executive agreement does not require ratification by the Senate. It’s not bulletproof; a future president could unilaterally abandon the deal. But for Obama, there’s a clear incentive for pushing to reach those 55 countries/55 percent thresholds as quickly as possible: Once the agreement goes into force, it requires a four-year waiting period before a country can withdraw. In other words, in the event that either Ted Cruz or Donald Trump—both vociferous climate change deniers—succeeds Obama in the White House, he wouldn’t be able to back out of the agreement until his [shudder] second term.

The odds are against the agreement taking force before Obama leaves office, because adoption by the European Union—which in the Paris Agreement acts as a singular unit—requires domestic actions by all of its 28 member states, which could take some extra time. Still, if the next president bails, he or she will have to pay a heavy diplomatic price for it, cautioned Elliot Diringer, executive vice president of the Center for Climate and Energy Solutions.

“Walking away from the agreement would instantly turn the U.S. from a leader to a defector,” he said, “and would almost certainly trigger a diplomatic backlash that would hamper our other priorities.”

The upshot is that the U.S. will likely join soon after Friday’s signing ceremony. A slew of other nations will follow, and the Paris Agreement will become binding international law sometime before 2018, when it calls for a global check-in on emission reductions.

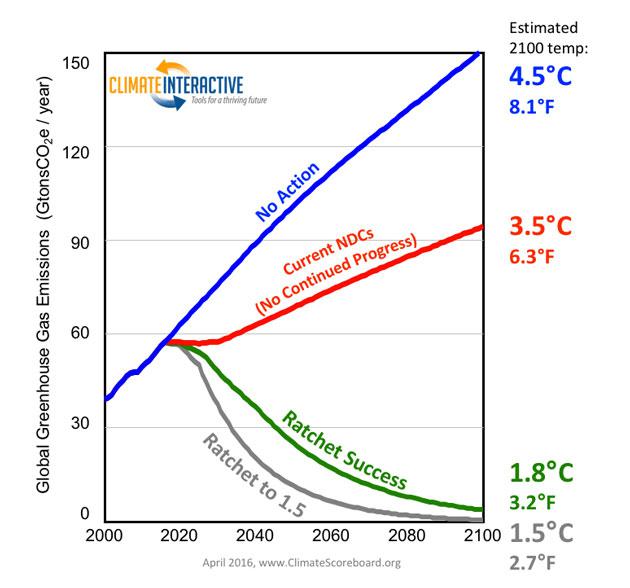

Of course, none of this puts the world any closer to averting devastating climate change than we were back in December. As they stand today, the country-level plans (nationally determined contributions, or NDCs, in U.N. jargon) enshrined in the agreement fall woefully short of the “well below” 2 degrees Celsius target. The chart below, from a recent analysis by MIT and Climate Interactive, shows a variety of possible future scenarios. The blue line is what would happen without the Paris Agreement—a world where the impacts of climate change would be truly horrific, and many major cities would become uninhabitable. The red line shows what will happen if countries stick to their current commitments. The green line is what a successful outcome of the Paris Agreement would look like (and, to be clear, even that level of warming will come with severe consequences):

Climate Interactive/MIT Sloan

As you can see, by 2025 or so countries need to be doing far more than they have committed to thus far. The Paris Agreement states that in 2020, at the next major international climate conference, countries must roll out new plans that go well beyond their current ones. So we’re very much not out of the woods yet. But we’re moving in the right direction, at least.

Since the first Earth Day in 1970, the holiday has generally declined into little more than a “news” hook for corporate communications people to harass reporters about eco-friendly guns and cheeseburgers and other dumb stuff. So it’s kind of nice to see the day being used for something of actual historical significance.