“For we might have run, and if we had run we should, I believe, have burst into flames.” So wrote H.G. Wells in “The New Accelerator,” a 1901 short story about a wonderful drug that speeds up its users, transforming them into near-meteors as they encounter the friction of the everyday atmosphere. “Almost certainly we should have burst into flames”! Science fiction treats constantly with time anxiety: Speed someone up and the world slows down. Send astronauts to space and they barely age as decades pass on the planet they left behind, as in Ursula K. LeGuin’s heartbreaking early novella Rocannon’s World, which also features flying giant cats. Or take the film Looper, which articulated a profound modern fear: That no matter what we do, no matter how hard we fight it, we are each of us doomed to become Bruce Willis.

And then there’s plain old everyday psychological time, the real, non-science-fictional stuff passing us by, which we perceive via the throbbing gearwork in our brains. The psychology of that kind of time—not the physics or philosophy of it—is the subject of British science journalist Claudia Hammond’s lively book Time Warped: Unlocking the Mysteries of Time Perception.

It’s a book about mental apparatus. How do we know a moment has passed? Hammond’s best bet is that we use the brain’s dopamine system along with a few other brain components. “We are creating our own perception of time,” she writes, “based on the neuronal activity in our brains with input from the physiological symptoms of our bodies.” The answer is not in our stars but in “the cerebellum, the basal ganglia, the frontal lobe and the anterior insular cortex.”

Ever since Oliver Sacks, pop psychology has trafficked in damaged brains, and in exploring the ways that science understands our perception of time Hammond makes the first half of her book into a catalog of head trauma. There is the man with the injury to the right frontal lobe who lost his ability to accurately estimate the passage of time, the folks in vegetative states who don’t blink in anticipation of an air-puffer (and thus have lost all sense of the future), the people who suffer brain damage and can’t differentiate between decades, and poor Henry Molaison, who, as treatment for his seizures, had a silver straw inserted into his brain and his hippocampus partially sucked out, and consequently, until he died 45 years later in 2008, never made any new memories, living forever in the past. Henry’s story was much like that of another man who slipped off his motorcycle and thus can’t think of the future.

Hammond is good company, that is, but this is a not-unpadded book. There is some blatant narrative foolery that hardly suits the story. The tale of a BASE jumper awkwardly named Chuck Berry is cut off, Da Vinci Code–style, literally in midair. “Now,” writes Hammond, “I’m sure you’re wondering what happened to Chuck Berry, our base-jumping glider pilot who was left suspended in the air, his body falling and time dilating. I’m afraid you won’t find out right away, as there are many other issues to explore.” Are there?

Anyway, Berry survives, the better to explain his perceptions; as he hurtled to earth time appeared to slow down and he made sensible decisions that saved his life. It’s not so much that we speed up in a crisis, exactly, as that the internal human clock that tracks time is variable. Hammond on ganglia is more fun than Hammond pacing out a skydiving story; neither the book or its readers are well-served by the imperatives of modern science writing (“We need stories to make this brain stuff palatable to mouth-breathers!”), the relentless adherence to form (Colon: The Story of Two Dots That Changed Publishing). Time is such an urgent subject, so local to our thoughts, that it needs very little narrative easing. The looming specter of death sells this book just fine.

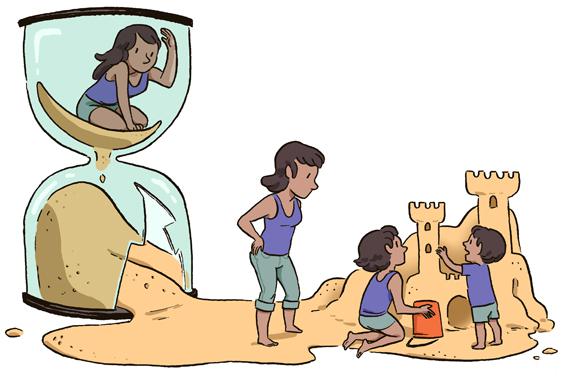

Once Hammond puts down the skull saw (around Chapter 4) things pick up, and she digs into big, ambiguous questions. A chapter on “Why time speeds up as you get older” is the good stuff. She starts with conventional wisdom, i.e. “A year feels faster at the age of 40 because it’s only one fortieth of your life, whereas at the age of eight a year forms a far more significant proportion.” Too simple, she says; as William James once wrote, “the days, the months, and the years [seem shorter]; whether the hours do so is doubtful, and the minutes and seconds to all appearance remain about the same.” It turns out that we form a “preponderance of memories” of life between age 15 and age 25: “first sexual relationships, first jobs, first travel without parents, first experience of living away from home.” This psychological phenomenon has a wonderful name: the Reminiscence Bump.

“We even remember more scenes from the films we saw and the books we read in our late teens and early twenties,” writes Hammond. One of the reasons time seems to speed up is that we actually have more memories of our youth. Which could explain why every generation freaks out over the one that follows: We’ve already made our memories, and to see these new little memory-factories with their own music, their own films, their own ideas when our own ideas still feel so fresh and fertile—their youth is an insult and it will not stand.

Courtesy of Ian Skelton

I remember feeling particularly old one day when I read a YouTube comment on a Kesha video. It said something like, in typically unpunctuated Tubese: this is garbag these morans don’t know god music whever happens to really music like Alanis. You’re only as old as the music you hate. Or consider the recent manufactured fuss over millennials (they’re lazy! they won’t pay attention! but maybe they’re great!) perpetrated by Time magazine. Just watch this video of Time editor Joel Stein living like a millennial for a day to see what happens when one type of reminiscence bumps into another. Or read Steve Albini complaining about the rap collective Odd Future. Ugly bumpings indeed.

As Hammond points out, many people see time spatially, going from left to right—unless they speak Hebrew or Arabic, which are right-to-left languages. For those people time moves in the opposite direction. And as for speakers of Mandarin, traditionally written top-to-bottom (even though it’s increasingly left-to-right on computer screens)? They are eight times more likely than English speakers to “lay time out vertically, usually pointing up into the air for earlier events and down for later ones.” Also, we think about time in terms of space, but not the other way around; no one says, Hammond points out, that a street is four minutes long.

Extrapolating just a bit, perhaps humans “see” time as a space, see their youths as a place. And when a new generation crops up it threatens the territory of the old one, they move in and colonize that zone of human life known as youth. Begone, Pixies, and make way for Imagine Dragons.

Not that Hammond would speculate like this; she sticks with the science. She isn’t afraid of a little ambiguity, though. The human understanding of time is hardly a solved problem; the Reminiscence Bump, while a real phenomenon, does not fully explain why time seems to speed up as you age. (You need to factor in also that we are making fewer memories every year—the Holiday Paradox, referring to how holidays seem to fly by but loom large in our memories.) Her agent is probably annoyed Hammond didn’t write The Reminiscence Bump: How Your Memories of High School Can Help You Predict the Future, but it’s nice to read a science book that isn’t buttoned up.

A well-researched meditation on how we see the future is the meat of the book; the real purpose of our memories, Hammond points out, may be to help us anticipate the future. Memories serve as our guides to decision-making; more so, the sorts of choices—and thus memories—we make classify us into human categories, whether we choose one marshmallow now or two later.

We know you can’t trust memories, which means, says Hammond, that you can’t trust your predictions of the future. On our way to a picnic we anticipate the picnic, not the traffic. On our way to the doctor we don’t imagine drinking a cold glass of water in a calm waiting room but rather being probed and questioned. “We expect the best of good events,” she writes, “and the worst of the bad. We imagine that if something grave happens to us, we won’t be able to cope, and that if something positive happens it will make us so happy that our lives will be transformed. But in both cases we will still be the same people we are now.”

Which is also why we all suck at scheduling; we set our deadlines months out never expecting to be as busy then as we are today. Everyone believes that they will somehow be better, less burdened, and more free in the future. But “forever yearning for that calm future where everything is perfectly organized sets you up for disappointment.” Which is a comfort of a sort. Because the great question of time is not, of course, “Why do I remember so many songs from 1989?” or “Will Chuck Berry survive his BASE-jumping excursion?” or even “Can dogs remember individual events?” (They can’t, which also means they probably don’t feel regret, which sounds great to me.) There’s one great question of time, one which of course this book cannot answer, but on which it gives a great deal of much-needed perspective: “How much do I have left?”

—

Time Warped: Unlocking the Mysteries of Time Perception by Claudia Hammond. Harper Perennial.

See all the pieces in this month’s Slate Book Review.

Sign up for the Slate Book Review monthly newsletter.