So you’ve started smoking. Congratulations! That means you’ve started beginning to think about maybe at least cutting back on your smoking a little, nicotine being a drug that ushers you along from blithe casual use to self-loathing zealotry with fantastic speed.

So you’re starting to think about quitting. Again, congratulations are in order. You’ve come to the right place. The Troy Patterson Stop Smoking Plan is foolproof, within limits.

Some, no doubt, will find it rather too specifically targeted.

For one thing, it is best suited to the light smoker—the sort of person conquering the urge to light up a mere four or five a day or, OK, maybe a couple more when stressed out by a particular concern, such as worrying about how you need to quit.

Further, the plan is designed for the smoker who has accumulated a lot of experience at quitting—who, as in the unavoidable Mark Twain quip, knows that quitting is the easiest thing in the world because he’s done it a thousand times.

With this invocation of Twain, we come to a third caveat: This how-to guide is written for the reader who actually likes to read. It represents a survey of the history of smoking-cessation literature, texts ranging from the best self-help books (guides to getting inside your own head, really) to the sharpest formulations of novelists and essayists (observations as precise as the click of a Zippo).

The Troy Patterson Stop Smoking Plan is not guaranteed to work for everyone. In fact, looking it over again, I see that it is not guaranteed to work for anyone, except for Troy Patterson. This writer’s plan is foolproof, but the writer is the only certain fool. Here at the beginning, the preamble to Step 1 (of 10), he vows that the period on this story’s last sentence marks a full stop.

Step 1: Using Google and the New York Public Library, skim across the history of anti-tobacconist literature. Such an experience is akin to getting hassled, for 400 years, by a million monkeys banging at a million typewriters that have only four or five keys. The Western world has said nothing new against the vices of tobacco since the days shortly after Walter Raleigh taking up the pipe and Jean Nicot bringing Catherine de Medici a snuffbox as a hostess gift.

The first medical authority to weigh in was King James I—“the proper Phisician of his Politicke-body”—with A Counterblaste to Tobacco, a treatise that set the template. In short, James wrote vehemently that smoking was gross, but he was writing in 1604, so it came out more like groff. In the United States, the prose practice of huffing about puffing blew up in the 1830s. The anti-tobacco voices joined the chorus of the temperance movement, and for the duration of the 19th century we got a lot of tracts and sermons deploring filth, waste, and licentious idleness. And yet the writers—addressing young boys and old bluenoses, not smokers—weren’t even interested in nagging you properly.

American publishers expressed little interest in the future ex-smoker until the turn of the century, when they mixed their printer’s ink with snake oil. An 1893 pamphlet titled King No-To-Bac, His Work in America existed to shill a fad-cure chewing gum, and the medical value of 1900’s Hypnotism in Mental and Moral Culture is conveniently indicated by the last name of its author, John Duncan Quackenbos. In reality, nothing much happened in the denunciation of tobacco between James’ Counterblaste and the Journal of the American Medical Association’s issue of May 27, 1950, which published lung-cancer research confirming the king’s hunch that tobacco “hath a certaine venemous facultie joyned with the heate thereof, which makes it have an Antipathie against nature.”

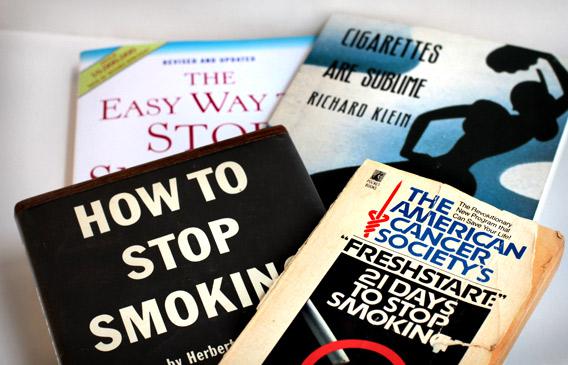

Step 2: Go to Barnes & Noble in search of a copy of The Easy Way To Stop Smoking, which is shelved not in Self-Help but, uncoddlingly, in Addiction. Its author, Allen Carr, ranks as the main man in the smoking-cessation game—posthumously so, having died of lung cancer in 2006 at the age of 72. At this writing, Amazon’s Books > Health, Fitness & Dieting > Recovery > Smoking section lists this 1985 book as its top seller. Other Easy Way editions and spinoffs claim places 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 13, 15, 18, and 20. These include The Easy Way for Women To Stop Smoking, the cover of which reflects the perceived preferences of women in its subtitle (… Without Gaining Weight) and in a numinous lilac design that calls to mind the retail packaging of Vagisil.

Photo by Juliana Jimenez for Slate.

Before building an empire of Easyway clinics, Carr was an accountant. Indeed, the smoking-cessation book is frequently the offering of non-experts. I mean, they are expert at hacking butts, but they tend not to be doctors or anything. In narrative terms, these books represent a subset of confessional literature, with its stories of amazing grace; testimony of profligacy establishes the authority of the voice offering salvation. Carr was a five-pack-a-day man: “I once burnt the back of my hand trying to put a cigarette in my mouth when there was already one there.”

So buy the book at Barnes & Noble and start in on it on the subway home. Perhaps you can skip the introduction. Another feature of this genre—not just a trope but a sine qua non—finds authors likening the tube of a cigarette to the bars of a jail cell. The writers hook the would-be quitters with figurative talk of escape and liberation. Carr maybe overreaches in comparing the thrill of extinguishing his last smoke to the relief of Nelson Mandela upon leaving prison. Maybe.

The first chapter tells you to pay attention. The second tells you not to attempt to quit before you have reached the finale. The fifth says that smoking presents a greater danger to the brain than to the lungs: “The worst aspect … is the warping of the mind. You search for any plausible excuse to go on smoking.” Once you get home, misplace the book for a while.

Duke University Press Books, 1994. Photo by Juliana Jimenez for Slate.

Step 3: Go to the Strand. Buy a book you already own—Richard Klein’s Cigarettes Are Sublime. (Your old copy—a gift from one of the girls next door senior year, the same “friend” who another time gave you a carton of duty-free Dunhill Reds—has been in storage recently because your den has become a nursery.) It was published in 1993 by, very perfectly, the university press at Duke: A school endowed by tobacco fortune sponsored an excellent silk-cut riff on the cultural logic of coffin nails. Its title toys with Kant’s idea of “negative pleasure”: “Cigarettes are bad. That is why they are good—not good, not beautiful, but sublime.”

Klein, a scholar of French by trade, sinuously riffs on Sartre and Baudelaire, on Bizet’s Carmen and Rick’s Café, by way of delivering a cultural critique with a practical purpose: “Writing this book in praise of cigarettes was the strategy I devised for stopping smoking, which I have—definitively; it is therefore both an ode and an elegy to cigarettes.”

Linger for a while over the idea of the elegy. Where a conventional smoking-cessation preacher tells the reader he has nothing to lose but his chains, Klein acknowledges that to quit is to experience a loss, and takes his time mourning a dying idea of fun. Klein never directly identifies the cigarette as a femme fatale, but after watching him explicate many a text in which a man compares his smoke to a mistress and test a number of elegant ideas about desire and mortality, you are left with the idea that he has subdued a seductress with the extravagant bouquet of his book.

Step 4: On a Sunday, step out to do some work over a late lunch for one. Realize that you haven’t had a cigarette today. You don’t really want one, but you don’t not want one, and no one whose disapproval you’d abhor is watching.

Or are they? The mind-warping Carr discusses includes the collateral damage of paranoia. You have gotten semi-surreptitious and ashamed and guilty about your habit, and to minimize the risk of running into anyone you might know from the neighborhood sandbox, you go out of your way, privileging side streets, walking a mile in the wrong direction for a Camel.

Take a sudden turn down a block where it seems the coast is clear. Notice a giveaway box of books in front of a townhouse and pluck a good omen from it—a hardcover copy of 1951’s How To Stop Smoking, the first blockbuster smoking-cessation book. The author is Herbert Brean, a mystery novelist and true-crime writer admired by Hitchcock. This was a guy who knew how to tell a story, and he creates a sort of meta-suspense by opening the book with a money-back guarantee: If the buyer doesn’t stop smoking, he’ll get back his $2.95—which, at the time Brean was writing, would buy a whole carton of fairly decent smokes.

Pocket Books, 1979. Photo by Juliana Jimenez for Slate.

After four chapters of patter, Brean sets out the preliminaries. He asks you—as authors in this genre always do—to make a list of the things you don’t like about smoking and hold onto it for later. (Yours starts: “$, smell, stigma …”) He tells you—anticipating a theme of Carr’s—to abandon the idea of will power, for “any psychologist will tell you there is no such thing.” He wants you for now just to think about quitting: “If you are not smoking right at this very minute, maybe it would be a good idea to take out a cigarette or pipe and light them up. Analyze what you do and what you taste and smell.” And you say, OK, no problem. This is a valuable exercise—the opposite of connoisseurship. The full acridity of the gas starts fumigating your buggy consciousness.

Having warmed you up, Brean then forms some ideas about habits, leaning heavily on the work of William James. His first suggestion is that you launch your new life with maximum momentum by telling everybody what you’re doing: “When you are seriously tempted to smoke, the thought of all the derisive laughter you’ll get for giving in may well carry you over the crisis.” Decide to write an article on the topic for a prominent online magazine.

Step 5: Go to your local independent bookstore. Buy one copy each of two things you already own. The first is the summer 2012 issue of Bookforum; your byline is among those on the cover, and you are vain. The piece inside is about Martin Amis and his novels Lionel Asbo and Money. By coincidence, John Self, the irrepressibly repugnant narrator of the latter, delivers one of fiction’s funnier lines on the habit—“Unless I specifically inform you otherwise, I’m always smoking another cigarette”—but Money is subtitled A Suicide Note, and this Stop-Smoking Plan is very consciously the antithesis of that.

No, the relevant material is in Amis’ later The Information and concerns the doomed Richard Tull and his “bond with cigarettes—this living relationship with death”:

Paradoxically, he no longer wanted to give up smoking: what he wanted to do was take up smoking. Not so much to fill the little gaps between cigarettes with cigarettes (there wouldn’t be time, anyway) or to smoke two cigarettes at once. It was more that he felt the desire to smoke a cigarette even when he was smoking a cigarette. The need was and wasn’t being met.

You connect this bit of The Information with Carr’s explanation of why burning his hand was not quite as stupid as it may seem: “Eventually the cigarette ceases to relieve the withdrawal pangs, and even when you are smoking the cigarette there is still something missing.” This becomes, at a certain point in everyone’s smoking career, a metaphysical truism, such that even he who is not a total fiend will admire a line of Klein’s about how smoking “seems to run desire backward—as if the fulfillment were even more the desire than the desire it fulfills.”

The second second copy of something you buy is the 2001 translation of Italo Svevo’s Zeno’s Conscience, a book also known as Confessions of Zeno. The novel, published in 1923, proceeds as if it were the self-analytic memoir of a serial failed quitter. Extract a minor motto from its dryly funny first chapter: “I believe the taste of a cigarette is more intense when it’s your last. … The last one gains flavor from the feeling of victory over oneself and the hope of an imminent future of strength and health.”

Pocket, 1986. Photo by Juliana Jimenez for Slate.

Step 6: Rummage around your apartment until you turn up your copy of The American Cancer Society’s “Freshstart:” 21 Days To Stop Smoking. It was handed down to you, a dozen years ago, by an old friend with a husk of Marlboro Reds in her voice, and you’ve been through it before, so you get to review the evidence of failure past: the brisk, can-do checkmarks and inquisitive squiggles of your old marginalia.

21 Days, published in 1986 and credited to Dee Burton, Ph.D., lacks the philosophical bent of Bream and Carr, but it’s packed with pragmatic pointers and soothing suggestions. On Quit Day, it says, drink a lot of water (for the fine satisfaction of the bloating) and carry a box of cinnamon sticks (for your lonely pie hole). The most essential instruction the book gives is to draft a one-sentence statement of commitment stating “as strongly and personally as possible what stopping smoking means to you.”

In other words, a mantra. Quitting represents a conversion, and it may well require a variety of religious experience. You should not resist believing this idea even and especially if you are the sort of person who, though embracing the ancillary pleasures of religion (Easter baskets, Seder briskets), looks askance at the enterprise of religious belief. The book says that this sentence “is meant to be a private statement between you and yourself, only,” but since you are writing a piece on the subject, you will, in advance of Quit Day, draft a snappy one and fix a simple echo of it to ripple across the prose, as if it were a note to self on a coded frequency.

Step 7: Have another cigarette while finishing the Carr book, the central advice of which arrives in the 32nd of its 44 chapters: 1) Make the decision to quit. 2) Don’t mope.

Sterling, 2005. Photo by Juliana Jimenez for Slate.

He knows what you’re thinking:

You are probably asking, “Why the need for the rest of the book? Why couldn’t you have said that in the first place?” The answer is that you would at some time have moped about it, and consequently, sooner or later, you would have changed your decision.

But there’s a bit more than that going on. To clarify, we turn to William S. Burroughs, a keen reader of Brean’s How To Stop Smoking. In a 1976 interview, he likened the book’s instructions to think calmly about smoking and write a list of what you don’t like about it to a Buddhist writing technique: “Look at your data, and a solution will present itself.”

Step 8: Run into one of your very few friends who still smokes and go have a beer. When the two of you, safely allied, step into the sultry night for a smoke, tell him how your project is going. He will point you in the direction of a piece in which David Sedaris memorializes his former life as smoker and his mother’s ragged breath. At the end, just abruptly enough, the scene shifts to a lounge at Charles de Gaulle Airport, where Sedaris stubs out his final and his final and then, OK, his ultimate final-final Kool Mild.

You like the way Sedaris describes the decision to quit—the click of the mental switch—by telling a story about a German woman whose command of English was slightly, blissfully unsteady: “I once asked if her neighbor smoked, and she thought for a moment before saying, ‘Karl has … finished with his smoking.’ ” The author scores a hit with the error:

“Finished” made it sound as if he’d been allotted a certain number of cigarettes, three hundred thousand, say, delivered at the time of his birth. If he’d started a year later or smoked more slowly, he might still be at it, but, as it stood, he had worked his way to the last one, and then moved on with his life. This, I thought, was how I would look at it.

Step 9 (optional): Start sharpening your appreciation—Romantic, but not wistful—for whiffs of secondhand smoke caught on the street. Commit to memory three relevant couplets from Charles Lamb’s “Farewell to Tobacco”:

Where, though I, by sour physician,

Am debarr’d the full fruition

Of thy favours, I may catch

Some collateral sweets, and snatch

Sidelong odours, that give life

Like glances from a neighbour’s wife;

Step 10: Search Google Books for a transcript of the awesomest thing in the history of celebrity endorsements—an infomercial Burroughs recorded for the 1975 edition of Bream’s book. The ending will change your life:

When you stop smoking, all habits are called into question. You begin to take a long cool look at everything you think and do. How much of your thinking and doing is predicated on a conviction that you can’t change? You have just proven to yourself that you can. So why stop with cigarettes? You can give up anything or anyone.

Well, that’s your kicker. Now start an essay. Now finish it. File to your editor and celebrate with a cigarette. In anticipation of this moment, you’ve switched to buying swank Nat Sherman MCDs, so rip the filter from one of those and duck out and light up. Watch the pretty wisps of poison disappear beyond the streetlamps. Breathe in. Breathe out. Move on.

—

See all the pieces in this month’s Slate Book Review.

Sign up for the Slate Book Review monthly newsletter.