Jane C. Hu is the author of “What Do Talking Apes Really Tell Us?,” which was published on Slate on Thursday. In the piece, Hu examines the very weird history of researchers trying to teach chimps, bonobos, gorillas, and orangutans to speak and use sign language, as well as the messy decline of ape language research. Hu spent more than two months researching and reporting for this piece. Slate Plus asked her about her experience.

How did you start writing about Koko and Kanzi?

I first learned about ape language research the way many people do—in my college psychology courses. Koko and Kanzi, the two apes in my piece, were easily the most famous—they were mentioned at least once in almost every psychology or linguistics class I took.

As I learned more about the field and went on to grad school, I noticed that many scientists were dismissive of the work, and had concerns about the interpretation of the data from these projects. Some even gossiped about the treatment of the animals, and the eccentricities of the researchers associated with the projects. After years of wondering about what was fact and what was fiction, I decided to do my own research and write this story.

What about apes, exactly, piqued your sense of curiosity and led you to write this story?

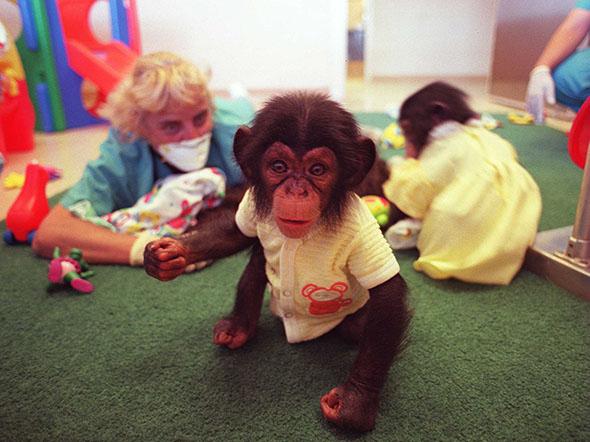

I think ape studies really get at the heart of what makes us human. We often think of ourselves as exceptional, and it’s humbling when you hear about a gorilla who keeps a pet kitten or a bonobo who knows how to make stone tools. But as a psychologist, I knew that there is a lot of disagreement in the field about what these behaviors mean about animals’ intelligence, and how applicable studies of individual captive apes are to wild apes.

How did you begin researching the story? Walk us through your process.

It was all through emails and phone calls; the key players were mostly in California or Iowa, and I was reporting from D.C. at the time. Phone calls with sources got intense, at times; people shared a lot of personal details, which I appreciate because I know they were deeply concerned about their privacy. (One source even emailed Slate to verify that I was actually a Slate writer!) While many of the sources were familiar with each other—the ape language research world is pretty small—I sensed that many had never told their story to an outsider.

The one thing that stuck out to me was the concern and love all of my sources had for the apes. People would get lost in telling me great stories about their interactions with these amazing animals, and often told me that the worst part about inner turmoil in these organizations is that they no longer get to see them every day.

Did the story quickly unfold? Or did you have to do a lot of digging?

Both, actually. Pretty much every time I talked to a new source, they suggested three more people I could talk to, provided information that changed the direction of the story, or illuminated a new fact that required more digging or verification. With all the info I collected, the piece could have easily been twice as long!

I spent about a month researching, and about a month writing and editing. The story seemed straightforward at first, but then there were curveballs that happened while I was writing: For instance, the court order for the ACCI happened while I was writing, as did the Gorilla Foundation’s new press release, and Koko’s dedication to Robin Williams. All of these developments seemed too important to leave out, so with the help of my (fantastic and very patient) editors Laura Helmuth and Julia Turner, I had to rework sections of the piece several times.

In the piece, you write that Dawn Forsythe warned you that sources may be reluctant to talk. “The human world of apes can get pretty nasty,” she said. Was it hard to find sources? Were you concerned that they wouldn’t speak to you?

I was initially concerned I wouldn’t get anyone to go on the record with their comments, but in the end, about three-quarters of the people I contacted got back to me. Sometimes it took them awhile, and in one case, they were not happy to hear from me and I had to talk to their lawyers instead, but it went better than I expected.

To be honest, I was surprised with how much people shared with me, not only about their experiences working at these organizations, but also about their personal lives. I learned about their new careers, their families, their emotions about the state of ape language research. I got the impression people were happy to have moved on, and happy that their experiences were finally being voiced.

What did you most hope to find out from all of your research and reporting?

I really wanted to know whether Koko was actually getting homeopathic treatments. All of my sources had mentioned this, but it just sounded so fantastical—but the Gorilla Foundation confirmed that it’s true.

What did you hope to explore more that you didn’t get to?

I wanted the focus of the piece to be on the apes, so I didn’t talk much about the scientists who raise them. But I find their foster parents deeply fascinating: They’ve devoted their lives to their research, and clearly, they deeply love these animals. Their close bonds with apes are both necessary to the research but also perhaps a hindrance to seeing their behaviors in an objective way. I mention in the piece that pet owners often have convictions about how smart their dog or cat is. Meanwhile, ape language researchers are often criticized for over-interpreting apes’ behaviors. It’s just kind of tragic that this bond that makes the research possible also has the power to complicate their findings.

What interesting challenges did you come across while writing this piece?

There’s a parenthetical in the piece disclosing that, for a brief time, my husband volunteered once a week at the Gorilla Foundation. When I first got the idea to write this piece, I decided I would not ask him for an interview to avoid any conflict of interest. (Luckily, it was easy to keep the topic off-limits, because I was living in D.C. while researching this piece, and he was in San Francisco.)

As I did more research and talked to more sources, I was really amazed at how well he honored his nondisclosure agreement. I’m usually pretty gabby about how my day went, but he did a truly remarkable job of keeping tight lips about his time there. He did, however, tell me on his first day there that he thought Koko liked him.

This conversation has been edited for length and clarity.