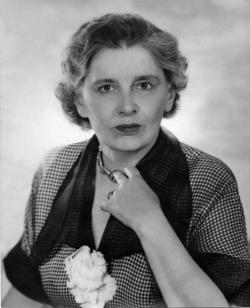

At one time, the novelist, critic, feminist, and troublemaker Rebecca West, whose birthday incidentally is on Friday, was considered one of the greatest writers of the 20th century. In 1947, her picture was on the cover of Time and her dazzling, ferocious prose was admired across the world; but now she is largely overlooked, underread, and out of print. Here, then, are 10 reasons to drop everything and read Rebecca West (and rather than her best known book, Black Lamb and Grey Falcon, I would suggest her stylish, innovative essays).

1) She was an ardent feminist (as she put it, “I myself have never been able to find out precisely what feminism is: I only know that people call me a feminist whenever I express sentiments that differentiate me from a doormat, or a prostitute”) but also a spirited and independent thinker. She was not afraid to attack or mock the suffragist movement when necessary, but she was also one of its most vivid voices. (She once made fun of one of the feminists from the New Freewoman “who was always jumping up and asking us to be kind to illegitimate children, as if we all made a habit of seeking out illegitimate children and insulting them!”)

2) Her fierce feminist inquiries were original and inflammatory; she was not content with slogans and bromides, and went deeper than other politically progressive women of her time, and in fact, our time. She wrote, for instance, a provocative attack on women, herself included, for devoting too much of their energy to love and relationships in the New Republic, denouncing them for “keeping themselves apart from the high purposes of life for an emotion that, schemed and planned for, was no better than the made excitement of drunkenness.” And later in a novel, The Judge, she elaborated the thought: “Since men don’t love us nearly as much as we love them that leaves them much more spare vitality to be wonderful with.”

3) She used her famously fierce wit to deflate male pompousness. In a lively attack on the formidable Great Male Novelist of the day, H.G. Wells, with whom she would later embark on a long affair, the 19-year-old West wrote, “Of course he is the old maid among novelists; even the sex obsession that lay clotted on Ann Veronica and The New Machiavelli like cold white sauce was merely an old maid’s mania.”

4) Though people like to think of the first “nonfiction novel” as Truman Capote’s In Cold Blood, West was doing that kind of innovative nonfiction writing long before. The idea of taking a cultural event, and investigating it with the storytelling eye of the novelist informs both her crime writing and her longer work. (See her brilliant meditation on the public trial of an Englishman who became a radio personality for Nazi propaganda, Lord Haw-Haw, The Meaning of Treason, which first appeared as a series of articles in The New Yorker.)

5) We associate a certain kind of cultural analysis, where the writer takes apart a social event and analyzes it in graceful prose, with the stylish deconstruction of new journalism, with writers like Joan Didion in the ’60s, but Rebecca West’s pieces doing just that were appearing in The New Yorker when the young Joan Didion might have been reading it. Take this passage about the wife of an accused murderer:

The suspicion that many men and some women felt about Mrs. Hume derived not from dissatisfaction at her explanation of her conduct, but from their reactions to her intense femininity. Her face, her body, her bearing, and above all, her soft preoccupied voice made an allusion to something outside the context and they assumed that something to be the truth about the murder. One might as well suspect a tree that blossomed in spring of making signals to another tree. What her whole being was alluding to, definitely, though with dignity, was sex.

6) Her life was not boring. She had H.G. Wells’ love child in her very early 20s, and built her impressive career in the midst of a colorful and dramatic series of romantic entanglements.

7) Her letters. When H.G. Wells died, she wrote to a friend: “Dear H.G., he was devil, he ruined my life, he starved me, he was an inexhaustible source of love and friendship to me for 34 years, we should never have met, I was the one person he cared to see at the end, I feel desolate because he has gone.”

8) What H. G. Wells called “her splendid, disturbed brain.”

9) Several impressive and established women writers found her so threatening that they were extremely catty about her. Take Virginia’s Woolf’s description of the very young journalist: “Rebecca is a cross between a charwoman and gypsy, but as tenacious as a terrier, with flashing eyes, very shabby, rather dirty nails, immense vitality, bad taste, suspicion of intellectuals and great intelligence.”

10) Her sentences. H.G. Wells said once that she wrote like God.