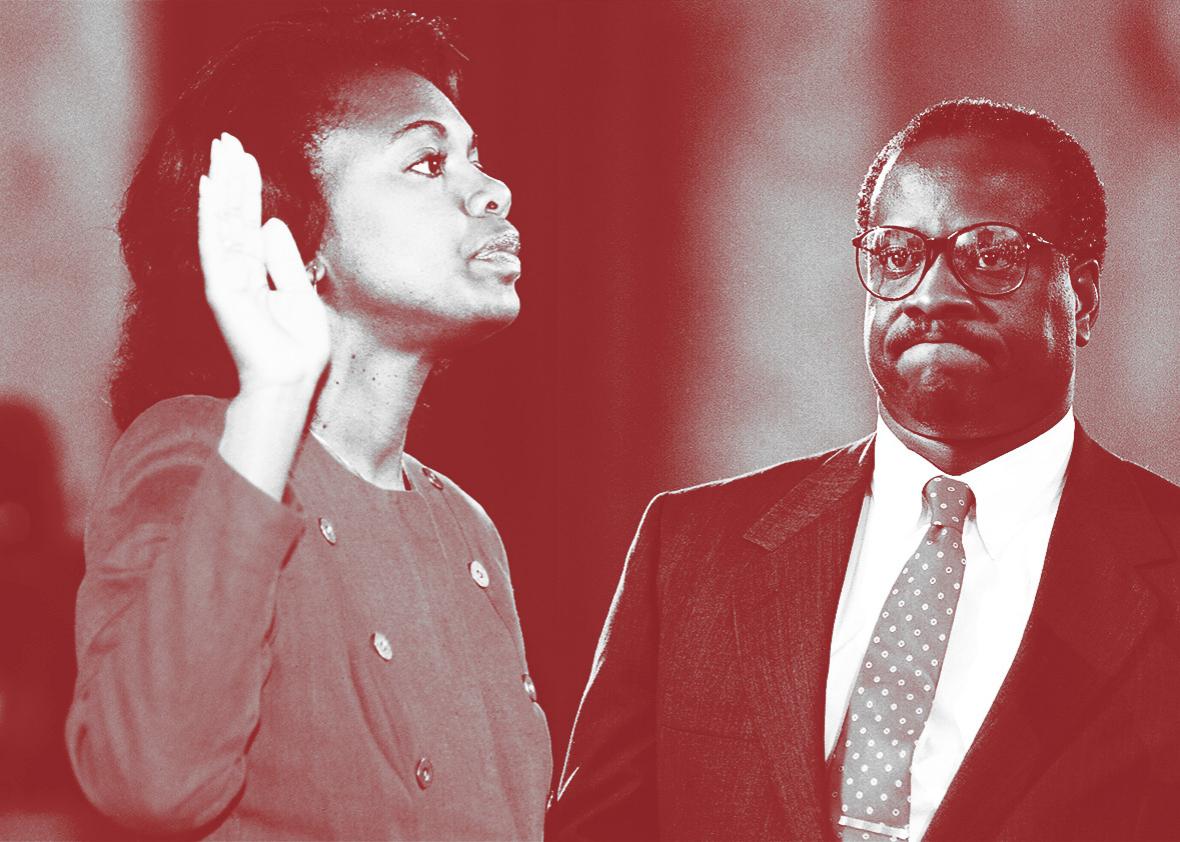

On Saturday, HBO will premiere the film Confirmation, starring Kerry Washington as Anita Hill and Wendell Pierce as then-judge, now–Supreme Court Justice Clarence Thomas. The movie recreates the three days of Supreme Court confirmation hearings that riveted the country in October 1991, launching a national conversation about sexual harassment in the workplace and helping to lead to a watershed year for women in elected office. Twenty-five years later, these hearings still resonate as one of the greatest political, sexual, and racial dramas in modern history. Slate senior legal correspondent Dahlia Lithwick recently spoke with Gillian Thomas, a senior staff attorney with the ACLU Women’s Rights Project and author of Because of Sex, about Confirmation. (The two writers were also college roommates, graduating in 1990.) An edited transcript of their exchange is below.

Gillian: When Anita Hill appeared before the Senate Judiciary Committee, we were just a year and a half out of college. I had heard the term sexual harassment and knew vaguely that it was against the law, but I hadn’t had much experience in the workplace, and I hadn’t started law school yet. I think the closest I had come to seeing harassment in action was Dabney Coleman in 9 to 5. Which, as we all know, has a happy ending—in that it does not have a happy ending for Dabney Coleman—so it hadn’t taught me much about how harassment plays out in real life.

But even by then, I’d experienced enough sexism that I instinctively believed Hill. And I recall my reaction when I read Sen. Arlen Specter’s explanation for why he hadn’t been troubled by the allegations: because Hill didn’t claim that Thomas had ever touched her or “intimidated” her. I was enraged by Specter’s setting the bar that high. It was one of so many examples of the committee’s cavalier attitude toward harassment.

That attitude was especially galling when you consider that the Hill hearings happened five years after the Supreme Court had found sexual harassment to be illegal, in 1986’s Meritor Savings Bank v. Vinson. Contrary to Specter’s suggestion, the court didn’t limit unlawful harassment to physical advances or to threats to fire the victim if she didn’t comply. The conduct only had to be “unwelcome” and sufficiently “severe or pervasive” to “create an abusive working environment.” The really ironic bit was that the court was endorsing the position of the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission, and Thomas was chair of the EEOC when Vinson was decided. But Vinson just didn’t prompt the kind of national dialogue—or national group therapy—that the Hill–Thomas hearings did.

Dahlia: I have to confess that watching Confirmation was as brutalizing as watching the documentary, Anita, was for me two years ago. I interviewed Hill at the time and came away amazed that she is still toiling away on sexual harassment law and still certain that she did the right thing in 1991, despite the fallout for her career and personal life. Like yours, my memories of October 1991 are of being riveted to the TV screen, shaken by the almost preternatural confidence Hill showed under pressure, and my mounting frustration that the men on the Senate Judiciary Committee seemed incapable of understanding what she was talking about, much less supporting her or knowing how to even question her.

In Confirmation, Kerry Washington captures that controlled, reluctant, dignified Hill perfectly. There is a whole heck of a lot of Olivia Pope happening here, but what Washington grasps so firmly is that Hill has no emotional margin in which to maneuver—to evince anger, as Thomas does, will destroy her. As Hill told me when I interviewed her about it, “He had a race, and I had a gender.”

Reading the account in your book of the Vinson case raised several chilling parallels that presaged the Hill testimony. Can you talk a bit more about the case and all the ways Vinson was a harbinger of things to come?

Gillian: The parallels are really striking. Like Hill, Mechelle Vinson was young, just 19, when she began working as a teller at a bank in Northeast D.C. Like Hill, she is black. And like Hill, Vinson hitched her wagon to the star of an older, accomplished black man—in Vinson’s case, Sidney Taylor, the bank’s branch manager, who was admired in the local community for ascending to the role after starting out as the bank’s janitor. Like Hill, Vinson faced the conundrum: If it’s the boss who’s harassing you, whom do you complain to? And like Hill, after Taylor began harassing her, Vinson didn’t immediately leave. For roughly three years, she stayed, although in her case, it wasn’t just professional blackballing she feared, but violence. According to Vinson, Taylor had threatened both her job and her life. She testified that Taylor raped her roughly 40 to 50 times, in addition to subjecting her to all manner of other physical and verbal harassment.

When Vinson did step forward, she faced the same under-the-microscope scrutiny that Hill did later. Witnesses at Vinson’s trial testified about her tight pants, her low-cut blouses, and her discussions about sexual fantasies, all in an effort to show that Taylor’s sexual conduct was not “unwelcome.” Some senators speculated that Hill suffered from erotomania and had scoured The Exorcist for pubic hair jokes ahead of her testimony. (Why those scenarios seemed more plausible than a powerful man saying obscene things to a subordinate is a head-scratcher.) Then there was the senators’ incredulity: Why didn’t you tell? Why didn’t you leave? As Alan Simpson infamously asked Hill, who followed Thomas from one job to another and kept in touch after they parted ways, “Why, in God’s name, would you ever speak to a man like that for the rest of your life?” That question defines privilege: The idea that you’d never need a professional connection or a paycheck badly enough to swallow your pride and be friendly to your harasser.

Dahlia: Yes, that moment in the film when Simpson attacks Hill is very powerful. In his view, any woman who continues to have any relationship with a former harasser is not a real victim of anything. At every turn, Hill is reminded that to stand up to her harasser is to lose, whether it’s done in the moment or years later.

When you tell the Vinson story in Because of Sex, you point out that then–EEOC Chairman Thomas initially wanted the agency to take the side of the bank. Even the final compromise brief filed by the EEOC contended that Vinson had never experienced a hostile work environment. Argh much?

Gillian: I’ll see your “argh” and raise you an “ugh.” The EEOC’s role in the Vinson litigation was a blessing and a curse for Mechelle Vinson herself. Here’s the backstory: In 1980, the EEOC issued revised Guidelines on Discrimination Because of Sex. It declared that harassment that created a “hostile work environment” was equally illegal as quid pro quo or “this for that” harassment—that’s the classic “sleep with me or you’re fired” harassment. Before the guidelines, most courts had only found quid pro quo illegal, because it was the only type that had tangible harm, such as a lost paycheck, if the woman refused.

That’s why the revised guidelines were of monumental importance to women such as Vinson. Vinson couldn’t show that she’d been punished for refusing Taylor’s sexual demands—for the simple reason that she hadn’t refused. She’d submitted. And she hadn’t lost any wages, either; in fact, she’d been promoted to assistant manager. But using the new guidelines as its road map, the appeals court hearing Vinson’s case found in her favor. It didn’t matter that Vinson couldn’t show financial harm, said the court, because it was also a harm to have one’s work environment poisoned with bias. This was a conclusion lower courts had reached years earlier in the context of racial harassment, when supervisors were leaving nooses on black employees’ desks and calling them the N-word.

By the time the Vinson case was ready to be heard by the Supreme Court, Thomas was at the helm of the EEOC, and the agency had to make a decision about whether to file an amicus brief supporting Vinson. In its brief to the court, the EEOC supported the concept of a hostile work environment but argued that Vinson hadn’t proved one because of her “voluntary” participation in sex with Taylor.

Despite her landmark legal victory, Vinson still faced years of litigation, because it was necessary to hold a new trial under the new hostile work environment standard announced by the court. The case eventually settled, and the modest monetary recovery allowed Vinson to pursue a nursing degree. After granting a few media interviews, she all but disappeared from the public eye. Hill, by contrast, came out of this trauma wanting to keep on talking about harassment. That’s presaged at the end of Confirmation, when Hill returns from Washington to her office at the University of Oklahoma College of Law to find every square inch stacked with letters from women thanking her for telling her story. As she reads them one by one, she realizes that she was telling theirs, too. And thus she answers the question she’d tearfully asked of her legal team a few days earlier: “What good have we done?”

Dahlia: The film chose to portray Hill sympathetically, and also to portray Thomas as a kind of bubbling cauldron of simmering rage. I found myself feeling rather sorry for him, and his high-tech lynching line pretty much took my breath away (Wendell Pierce does it verbatim). What did you think about the ways in which both Hill and Thomas fare better dramatically than the buffoons and villains on the Judiciary Committee?

Gillian: You’re more of a softie than I am; even the acting genius who brought us Bunk Moreland couldn’t make me feel sorry for Thomas. I can understand why John Danforth was unhappy about his portrayal, though. As played by Bill Irwin, he practically rubs his hands together in glee when he learns from a reluctant minion that some Oral Roberts law school students had called the office claiming that Hill sprinkled pubic hairs among their graded papers. Arlen Specter’s cross-examination of Hill in the film is just as tone-deaf as I remembered it, and Joe Biden gets pretty well drubbed, too, with a spot-on imitation by Greg Kinnear, for his lack of control over the hearings. I’ve come to love Joe, but this was not his finest hour. Biden’s piece de resistance of poor judgment, of course, was deciding against calling an obviously relevant witness, Angela Wright, who claimed under oath that Thomas had harassed her, after Biden allowed hours of irrelevant testimony from Thomas supporters such as John Doggett, who posited that Hill had a tendency for being attracted to irresistible but unattainable men like himself. As the movie has it, it was Biden’s fear that Danforth would disclose the puerile Oral Roberts bros’ allegations that kept him from calling Wright.

Hill’s “case” before the Judiciary Committee was cut off at the knees by Wright’s nonappearance. If she had been allowed to speak, the question would then be out there: What’s the likelihood of Thomas hiring two erotomaniacs to work for him? The same thing happened to Vinson at her trial; other female bank employees with tales about Taylor’s gropes and leers and discussions of pornography were excluded as irrelevant to what happened between Vinson and Taylor. Thankfully, such evidence is much more commonly admitted in such cases today.

Dahlia: I like to show clips of the real Hill–Thomas hearings to law students. It’s important to recall, as you say, that it really wasn’t all for nothing, that legal progress often happens in ragged fits and starts, and also that the Thomas–Hill hearings did launch a sea change not just in female electoral politics—and women on the Judiciary Committee—but also with respect to unprecedented reporting of sexual harassment claims at the EEOC: There was about a 40 percent increase in the number of charges filed with federal and state agencies between the 1991 and 1992 fiscal years.

Gillian: The aftermath of the confirmation hearings also brought more expansive sexual harassment rulings from the Supreme Court. In 1993, the court considered a case in which the alleged misconduct was far less severe than that at issue in Vinson and still, in a unanimous vote, found the conduct illegal. Importantly, the court made clear that for an environment to be illegally “hostile,” the victim needn’t show that her work product declined, or that she needed counseling to cope with it, or other measurable evidence of harm; it’s enough to show the harassment was bad enough that a “reasonable person” would have found it hostile. A few years after that decision, the court extended Title VII to cover same-sex harassment.

Of course, the lesson from all of this history is not that sexual harassment peaked with Anita Hill’s revelations. Far from it. Harassment charges with the EEOC and related agencies remain at roughly the same level they were after the Hill–Thomas hearings. News headlines are full of galling examples virtually every day. Women in male-dominated jobs such as construction and law enforcement are especially vulnerable, as are women in jobs dominated by “low-status” groups, such as undocumented workers or teens.

To me, the enduring value of the Hill–Thomas hearings is that men started hearing from the women in their lives about the sexual harassment that had happened to them, and women began speaking frankly with one another about their own experiences. The aggregate effect of those one-on-one conversations—occurring at the same time that the court was creating a legal architecture for addressing harassment—spawned one of those rare moments when you could practically see the tectonic plates of the cultural landscape shifting. We’re still having the conversation about men and women and sex and race, but now we have a far better vocabulary.