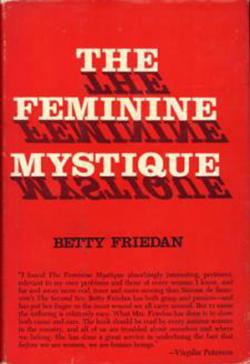

OK, Emily, you’ve knitted me into a corner: I sounded just as judgmental as I accused Friedan of being, didn’t I? It’s a useful reminder that it’s nearly impossible to avoid picking sides in the so-called mommy wars, even if you’re just an innocent bystander claiming no dependents on your tax return. To wit, we’re arguing over just how soft a softer feminism is allowed to be. (Depends on what yarn you’re using for all that knitting I guess!) But that’s another of the reasons this book was worth reading 50 years on. One of the things Friedan did awfully well, I thought, was show us that all that judgment toward women’s choices about work and motherhood didn’t just rise up like so much bile from deep within the American soul. You mentioned the sex-directed education at colleges—which, thank god, has gone the way of Spam and Jell-O salad—but she also spends a certain amount of time ripping into some familiar contemporary villains: corporate America and women’s magazine editors.

I happened to be flying while I was reading The Feminine Mystique, and while I always pack my tote full of Atlantics and New Yorkers, immediately upon spotting a Hudson Booksellers, I toss them aside for Martha Stewart Living and Glamour. (Yep, I’m really owning this third-wave stuff here.) So this particular flight, I ended up toggling between Friedan’s devastating survey of the intellectual wasteland that the women’s magazines of the time represented and an impromptu survey of the current situation. Ladymags are a constant source of grist for bloggers (Jezebel basically made it onto the map by publishing unretouched photo proofs from one of the glossies), but this was a nice reminder that, even though there might not be the amount of serious reportage we’d like to see in them and they might be obsessed with appearance and man-catching to a fault, basically all women’s magazines now are written from a feminist point of view, and have been for years now. Real Simple helps you organize your drawers more efficiently because you’re a busy working mom. Marie Claire runs tips on how to get ahead at the office. The default mode is a far cry from the one Friedan describes. Sure, some of her criticisms might still ring true (“Politics, for women, became Mamie’s clothes and the Nixons’ home life”), but at least we’ve moved on from headlines like “Are You Training Your Daughter to Be a Wife?” or “Femininity Begins at Home.” And I sincerely doubt that American women would more readily identify with a crippled young boy than with a “spirited heroine working at an ad agency,” one finding she cites from a popular magazine’s survey of its fiction readers.

Of course, then as now, the magazines are really just moving product for the corporate guys. Friedan argues that in large part it was manufacturers, needing to create a market for their new dishwashers and washing machines, who helped invent the stifled vision of ’50s femininity. “In a free enterprise economy we have to develop the need for new products. And to do that we have to liberate women to desire these new products,” she quotes an insider saying of the new time-saving household devices, which should theoretically have freed women up to do other things with their time. “We help them rediscover that homemaking is more creative than to compete with men. This can be manipulated. … The big problem is to liberate the woman not to be afraid of what is going to happen to her, if she doesn’t spend so much time cooking, cleaning.” That “liberation” meant, in fact, directing her thoughts: “We liberate her need to be creative in the kitchen. If we tell her to be an astronomer, she might go too far from the kitchen” and all of its expensive doodads. We don’t spend so much time thinking about cleaning anymore, but substitute in, say, “waxing” and “exfoliating” and “shopping,” and you’ll have a rather up-to-date Marxist-feminist reading of why we’re all dropping so much cash on trying to look and feel and be pristine.

And that’s the real bummer here. The thing that Betty wanted most, in writing this book, was to re-instill young women with a sense of possibility (“I felt the future closing in—and I could not see myself in it at all,” she writes of her young self), to have exciting, not terrified, ideas about what to do with all that time spent not cleaning. It’s difficult to maintain that true sense of possibility and adventure when you’re feeling the pressure to be perfect—in the mirror, at work, at home. Unlike in Betty’s era, it’s not gone unnoticed, because the constant microscopic inspection of women that helped create the problem has also helped diagnose it. And I suppose that brings me right back around to my original critique. It’s not that I want to go back to a problem that has no name, exactly, but I wouldn’t mind a little less name-calling.