On a balmy May evening at a D.C. rooftop bar with a view of the Capitol, two dozen or so Republicans milled around drinking topical cocktails. There was the bourbon-based Pre-Existing Condition. Russian to the White House paired vodka with elderflower and grapefruit. The Spicey Margarita paid homage to the long-suffering, bush-hiding, “Holocaust center”–ing White House press secretary.

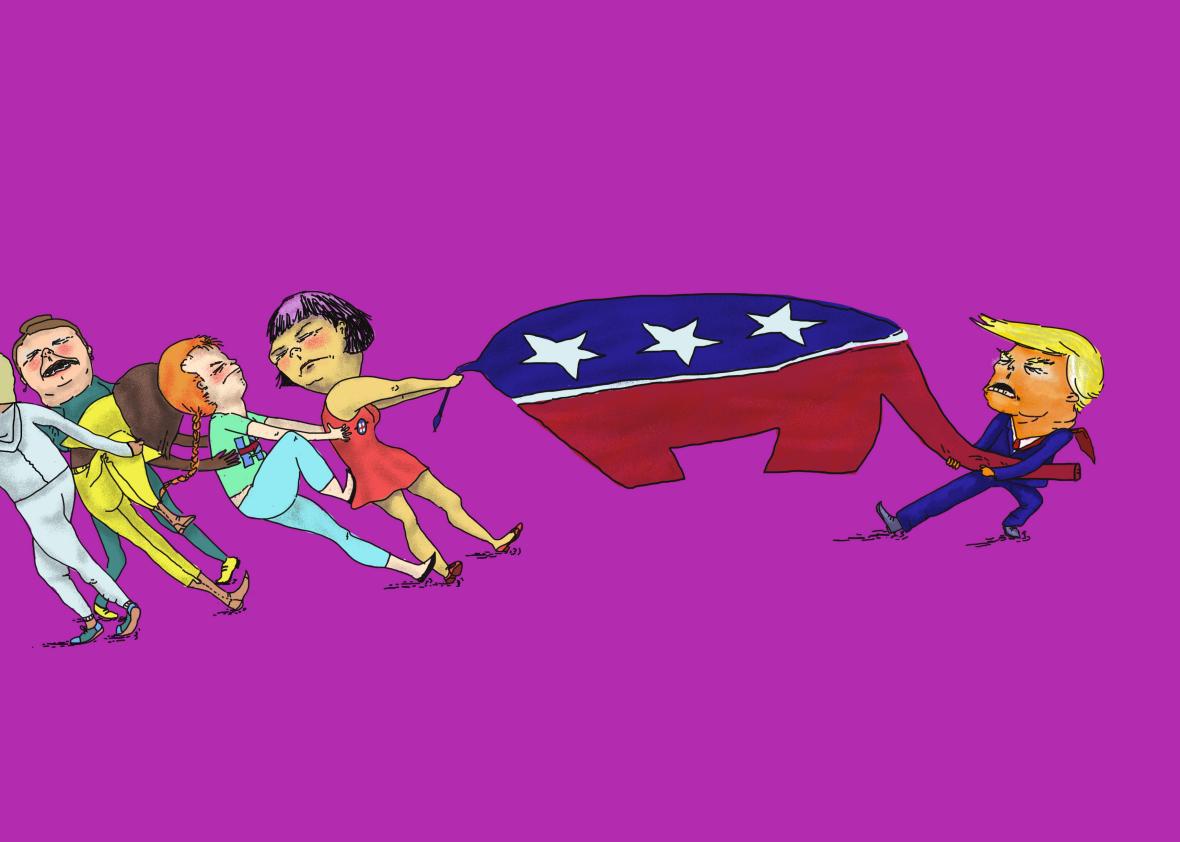

The crowd had gathered to celebrate the launch of Republican Women for Progress, a nonprofit that grew out of opposition to the party’s de facto leader. Formerly named Republican Women for Hillary—a loose network of women who temporarily turned against their party to support the Democratic nominee over Donald Trump—RWFP is fashioning itself as a home for women who want to see the GOP abandon Trumpism in favor of a more inclusive, moderate ideology. Meghan Milloy, one of RWFP’s co-founders, says the organization’s goal is eventually to become “an EMILY’s List for the reasonable Republican woman,” name-checking the 30-year-old fundraising and training organization for pro-choice Democratic women. What does “reasonable” mean to Milloy? “Not being an asshole, mainly.”

“Every day, I think Hillary Clinton should have been president,” says 31-year-old Jennifer Pierotti Lim, who founded Republican Women for Hillary and RWFP. “There were a number of policy areas I didn’t agree with her on, but when it came to biggest faults of Trump—national security and trade policy and general adeptness at being a leader—Hillary came out far ahead.”

The women of RWFP see Clinton as a moderate, even a “moderate Republican,” as board member Ariel Hill-Davis, 32, puts it. A self-professed “business conservative,” Hill-Davis can sound a lot like a Democrat: She believes in “reasonable gun control,” abortion access, and reforming a justice system that’s imprisoned “an entire generation of black men.” She protested Trump’s travel ban and is passionate about LGBTQ rights. But Hill-Davis comes from a long line of Republicans and says she “salivates” at the thought of entitlement reform. Her years working for trade associations in the mining and manufacturing industries shored up a belief that regulations on businesses can poison a healthy economy. “Let’s just say I don’t have a problem with the fact that Scott Pruitt is running the EPA,” she says.

Milloy, who’s 30, was turned off by Trump’s misogyny and general incompetence during the campaign—and still is—but also felt that his positions on trade and immigration didn’t reflect traditional Republican values. “We kind of want to rewind to, I guess, if there ever was an era of the moderate Republican that really does care about small business and the middle class, and wants to grow the economy, and isn’t focused on wedge issues,” she said at the launch party. Milloy had hoped GOP leaders could personally oppose things like LGBTQ rights and abortion while publicly recognizing that the Supreme Court had already affirmed these rights. The majority of the country supports those rulings, and though RWFP women harbor a range of views on abortion, they support gay rights and agree that extreme anti-choice measures, like shutting down women’s health centers in the way of Texas, make for bad public policy.

Tim Lim

Yet the GOP has doubled down on social issues, which wouldn’t appear to help them court younger voters. The Pew Research Center put millennial support for equal marriage at 71 percent in 2016, when 62 percent of people aged 18–29 said abortion should be legal in all or most circumstances. While in the last decade young people have increasingly forgone identification with either party—a trend that should concern Democrats, too—millennials have become more likely to identify as liberal, while the proportion of conservative millennials has remained constant.

In the short term, RWFP’s leaders want the group to function like a hybrid think tank and civic participation club, releasing in-depth policy analysis and helping women get involved in politics as advocates or candidates. On top of the list of role models for the group are Sen. Lisa Murkowski of Alaska and Sen. Susan Collins of Maine, both Republican women who’ve recently opposed their party in votes on Planned Parenthood funding and Secretary of Education Betsy DeVos’ confirmation. The leaders of RWFP believe that if there were more Murkowskis and Collinses in office willing to criticize or break with their own party, the GOP might not have ended up with candidate Trump.

Eventually, RWFP intends to form a political action committee and train would-be candidates themselves. The group is building on an existing network of 10 state chapters left over from pre-election organizing as Republican Women for Hillary, a group Lim started in May 2016, after Trump became the GOP’s presumptive nominee. She was motivated in large part by his history of misogynist treatment of women. At the time, Lim was working as director of health policy for the U.S. Chamber of Commerce and assumed her side gig would only last through the election, no matter who won. “But what we learned through the campaign was there were so many Republican women who felt the same way as us, who felt so disconnected from the party and didn’t agree with the direction the party was going,” Lim says.

Tracy Russo

She earned a speaking slot at the Democratic National Convention and, with Milloy, organized fellow Republican Hillary supporters in the group’s state chapters to join local get-out-the-vote efforts. The group wanted to give cover to other Republicans, especially Republican women, who might be wary of publicly rebuking Trump on their own. They held “coming-out parties” for lifelong Republicans who had to break it to their parents or significant others that they’d be casting votes for a Democrat. They also met older Republican women who kept their misgivings about Trump to themselves because they were raised to think it was gauche for women to talk politics. Some said they wanted to vote for Clinton, but their husbands wouldn’t let them or even filled out their absentee ballots on their behalf. “We were like, ‘Oh my gosh, what?! Are you in the voting booth together? Just do what you want,’ ” Milloy says. “That’s our target, to empower [women]. Don’t let your husband, or anyone, tell you what you need to be thinking or feeling or voting.”

Lim, Milloy, and Hill-Davis spent election night at what was supposed to be a victory party they held with a like-minded organization called Never Trump. “I was an absolute mess,” Hill-Davis recalls of that night. “It was really eye-opening for me,” she says, to realize “where our country actually is in terms of how we view strong women. I work in a man’s world, and I’m used to interacting with men, so seeing a really strong woman get torn down for all the things we elevate and praise in men was brutal.”

The Republican Party generally abhors anything that smacks of identity politics when the identities aren’t white and male, and that would include initiatives such as RWFP that strive to help a particular demographic get a leg up. RWFP members believe that the Republican Party, at its best, stands for equal opportunity but not necessarily equal outcomes. This election cycle reinforced their suspicion that equal opportunity for women in politics is a myth. It “fundamentally changed my understanding of the country,” Hill-Davis says, to see misogyny, among other forces of hate, keep a pre-eminently capable candidate from besting the least-qualified candidate the U.S. had ever seen.

Part of RWFP’s goal is “pushing more women to run in general,” Hill-Davis says. “But the other part is carving out a safe space to be a Republican that’s not toeing the current party line. I’ve been called a RINO since I got to D.C. But from my perspective, things like LGBT rights and access to reproductive health care for women—those are actually small-government issues,” in that they protect people’s rights to make their own decisions about their bodies and lives. Other RWFP leaders are chagrined by Republican state legislators’ obsession with anti-transgender bathroom laws and Attorney General Jeff Sessions’ crusade for tougher prosecution of minor drug offenses. The group prides itself on accepting supporters who hold a variety of political viewpoints. For instance, some women of RWFP stayed home from the Women’s March on Washington because of its exclusion of anti-abortion groups, but Lim staffed a hospitality suite for marching RWFP supporters in a friend’s D.C. apartment near the march route.

Milloy cringes at the memory of Vice President Mike Pence’s viral photo of his health care meeting with the House Freedom Caucus, capturing more than two dozen attendees with not a woman visible among them. At the very least, she wondered, didn’t anyone in the room—all members of a party that’s regularly criticized for its treatment of women—think about the crappy optics of that meeting? After Mitt Romney’s defeat in the 2012 election, the Republican National Committee’s “autopsy” concluded that women “represent more than half the voting population in the country, and our inability to win their votes is losing us elections.” Then, oddly enough, they went ahead and nominated Donald Trump. Odder still, he won. “Right now I think a lot of Republicans in the party think, ‘Well, we won. We own the whole government, so we’re kind of winning right now. Why would we go back and look at things that might not be working?’ ” says Lim.

The women of RWFP are hanging their hopes for a GOP reckoning on the 2018 midterm elections, when they hope big Republican losses will force party leadership to shift course toward the center. “I don’t think I have it in me to be a Democrat,” says Hill-Davis, due to her commitment to fiscal conservatism. But since the Republican Party is currently full of people “putting party before country,” she says, RWFP plans to build its own activist infrastructure and candidate pipeline outside party bounds.

Democratic women have a formidable roster of role models in state and national politics, plus a zillion organizations that can help them run for office, but there are comparatively few bipartisan candidate-training groups for women and barely any that focus on Republicans. Most of the ones that do exist are closely tied to the national party and led by people like Carrie Almond, president of the National Federation of Republican Women, who told me in January that she was “blown away with the excitement and enthusiasm” of conservative women in support of a President Trump. Republican women dismayed by Trump’s victory—and by the national party leadership that boosted Trump and some of the far-right obstructionists in Congress into office—don’t mesh with that crowd.

But those same disaffected Republicans wouldn’t feel at home with Democrats, either. The women of RWFP maintain that they can have a bigger influence on the country’s direction by forcing the party to change rather than giving up and registering as independents. Part of their loyalty to the GOP is cultural: Lim says the Republican Party inspires a “tribal mentality” in members. That’s useful when it comes to voter turnout but not when it delivers victory to candidates who will sour voters on the party in the long term.

Even for Lim, tribal allegiance can only go so far. “If Trump is elected a second time, that would make it pretty hard to think we could bring the Republican Party back” to where RWFP wants it to be, she says. If the GOP accepts Trumpism as the new norm, Lim might leave the party to which she’s staked her professional name. “You do have to draw a line somewhere,” she says. “It’s hard to even know where that line is these days.”