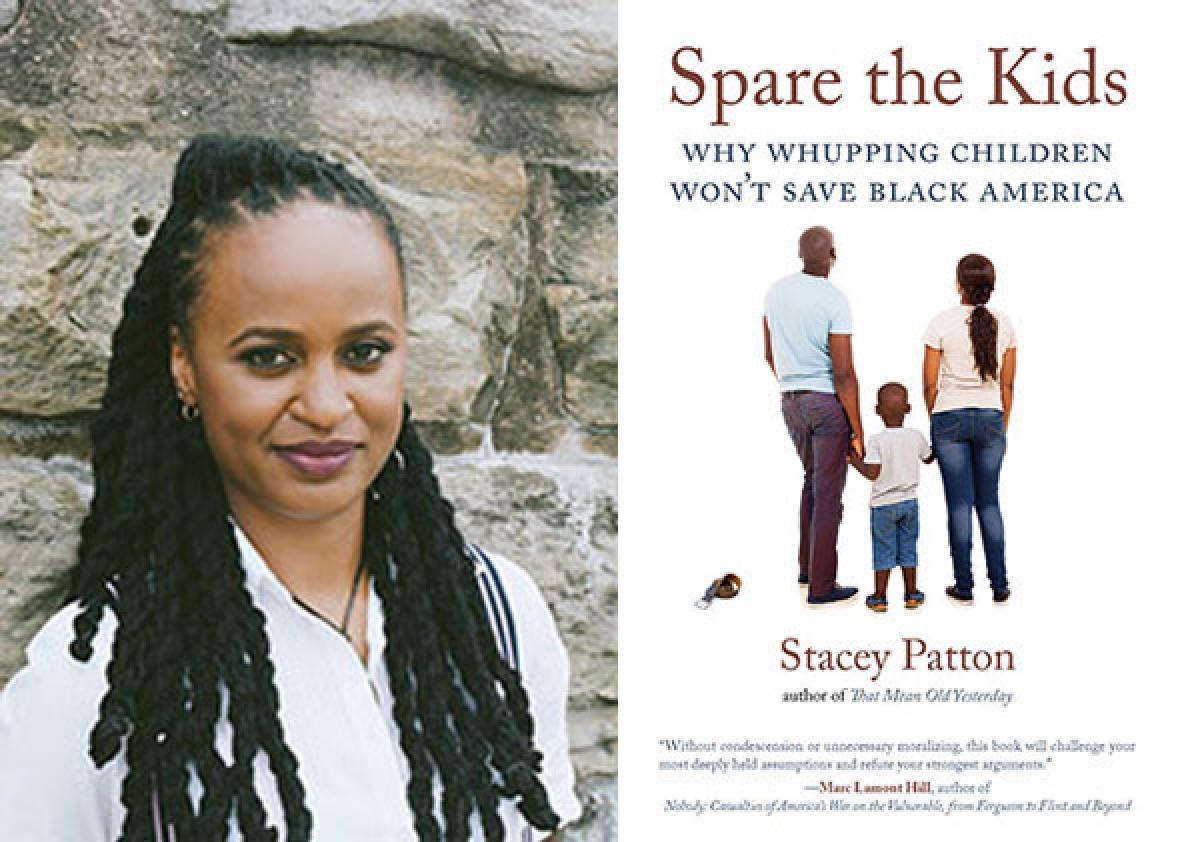

In her new book, Spare the Kids: Why Whupping Children Won’t Save Black America, Stacey Patton explores the deeply embedded practice of corporal punishment for black children, both within and outside of the home. Patton, an assistant professor of multimedia journalism at Morgan State University, drew on decades’ worth of research and interviews with adult victims of what she considers childhood abuse and traced the history of spanking to European parenting styles that were eventually passed on to black American slaves. Ultimately, she advocates fiercely against hitting children in any way, as well as the embrace of such parenting tools within black culture.

Patton spoke with me by phone for almost an hour. In our conversation, which has been edited and condensed, she discussed her own abuse as a child, the pushback she’s received from those within the black community, and her struggles to find the right tone for the book.

You write that many adults who grew up having experienced corporal punishment in one form or another are in denial when they claim to have “turned out fine”; you see them as the survivors of “unrecognized trauma.” As someone who was beaten by your own adoptive parent, when did you first identify yourself as abused, and how did that recognition come to be?

It happened when I was 5 years old, the first time my adopted mother backhanded me in the mouth. I had never been hit before, and so when she did this, my whole world came crushing down. It was a person I was supposed to trust and depend on for nurturing and safety, and from that moment I felt unsafe around her. And it continued to escalate as I got older. She started using objects, and I knew it was wrong. I didn’t have the language as a child to explain it, but it never felt good, and no matter what I heard from her, from the community, from folks at church—it didn’t feel like protection. … So, I never normalized it, and maybe that was because I was adopted, and I never felt any emotional connection to her.

Your adopted mother—was she black?

Yep. Black and middle class. She was not a single mom. We lived in the suburbs. She was Christian. Plus, I had spent five years in a foster home before coming to their house. People start hitting their children at toddler [age] before they start walking or talking, so the child is beginning to normalize that pain before they’re able to develop verbal and cognitive skills. When you hit children when their brains are still developing, particularly in that 0-to-3 age range … you’re rewiring the child’s brain to avoid pain.

The hitting is presented in the context of love and safety. There are all these justifications that the child hears for why their parent is assaulting their body. And folks grow up with these messages wired and etched into their brains … [so that] they grow up, and they can’t even remember the betrayal, the hurt, the fear, and the anticipation of adults who are about to beat them. What they’ve done is they’ve grown up to invert the violence as something good, and they’ve held on to the adult justification. So it is denial, it is a need to absolve the parents, to not say, “My mother or father was wrong.”

It seems like you feel because you were a little bit older, you were able to sort of sidestep the feeling that it was “love.” You always saw yourself as being abused, unlike a lot of other adults.

Yes, always and no matter what it was called—some people will say to me all the time that there’s a difference between spanking and abuse. And I say, well: Spanking and abuse are all violent. They stem from two distinct places: One might be an instinct to love and protect, and the other is malicious. But both can produce the same karma. We’ve got 50 years’ worth of science that shows that spanking is harmful to children’s bodies, their brain development, their IQ, and spanking is a form of chronic stress that can set a child up for chronic health issues like obesity, diabetes, heart issues, cancer, and even a lower life span …

There are plenty of people I’ve met that have had their biological parents raise them from birth and feel the exact same way, that they never felt this was normal behavior.

There are people who have been spanked once or twice in their lives, and maybe it doesn’t affect them in the same way. Do you still feel that is just as harmful, or close to being as harmful, as constant beating and abuse?

Think of it from the perspective of an adult: Let’s say you have a 30-year-old person who has been slapped in the face once in their adult lifetime. That’s a pretty traumatic thing, and they’ll remember it and they’ll talk about it, because it’s a violation of the body. So there are plenty of people who’ll say, “I only got one or two spankings,” and they’ll talk about them, and you can tell just by the way they talk about them that it left an impression on them, that it was still traumatic. Did they necessarily experience a lower IQ or other psychological issues because of it? Maybe not. The science will tell you that once or twice in a child’s life doesn’t mean that it’s going to lead to long-term damage. But it’s always an assault, no matter how you do it, no matter how many times you do it, no matter what the parent’s intent is—it’s all violence and it’s wrong.

Hitting between adults is illegal. A man hitting his wife or his girlfriend is called domestic violence. If we hit animals it’s called animal cruelty. But kids are the only group of people in this country where it is codified in law to assault their bodies.

Within the title of your book, you refer to “whupping,” and also, frequently within the book, “beating.” I was spanked as a child, and I think I might be one of those people who doesn’t consider myself an abuse survivor, mostly because the spanking probably happened a few times. What made you decide to focus on the harsher aspects of corporal punishment?

I use the term “whupping” because that’s a term that black people use, and a lot of times when black people talk about spanking, they’re dishonest. I’ve talked to people who say I was spanked as a kid or whupped, and it wasn’t abuse, but then when you ask them, how was your body hit, they’ll say they were slapped in the face, that a parent used a belt, or a switch.

I’m not into conversations about how you appropriately strike a child’s body, how you appropriately hurt their body. And when you look at the fatalities site—I looked at the past 10 years of child maltreatment reports that are put out by the Children’s Bureau each year, and I tallied the fatalities. Black people over the past 10 years, from 2006 to 2015, which were the latest available numbers, have killed over 3,600 children as a result of maltreatment. Now, when I talked to district attorneys and child-welfare professionals, they will tell you that these severe cases of abuse where there’s injuries or marks, or even the fatalities, are not being caused by sadistic parents who are torturing their kids; they’re caused by parents who consider themselves [to be] “spanking” their kids. They all started off spanking, and at some point, maybe they hit too hard, that one day they were extra frustrated, and they smacked the kid and maybe the kid fell and hit his head. Or maybe they punched the child on the body, and it caused internal bleeding. When you listen to the reports, you hear the parents say over and over again, “I just hit hit him too hard this time; I didn’t mean to do it.”

As we know with the case of Tamir Rice and other high-profile cases, black boys and girls are often perceived to be way older than they are because of long-held stereotypes about blackness. What I found interesting was how you lay out that even black parents have internalized this—that black innocence is not a real thing. You talk about the stand-up comedians who have joked about it, especially Bernie Mac, and how they assume that black children are just terrible from the get-go, and the only way to set them right is to beat them. And I’d never really thought about it in that light before. Have you found that looking at it from that perspective helps advocates of spanking and beating change their thinking?

Our entire ecosystem is full of this negative imagery, negative stereotypes and predictions about black children. We were always a problem described by the larger white world, and our parents internalized those messages, and you could see them come out in the way they parented us from a place of fear. And so the beatings were designed as some kind of [preventative measure] to save us from going to prison, for example. But if beating black children were so successful in keeping us out of prison, we wouldn’t be having this conversation about mass incarceration and police brutality …

To some degree, [people are receptive to this connection], but I get a lot of pushback from people accusing me of playing respectability politics, pathologizing black people … Some of these people, I just let them sit in the dark; I don’t waste my time with them. I focus my attention on the parents who want to make a change, who want to do something different. I find that when I talk about this issue in a holistic way … when I take them back through 2,000 years of European history to show them how sadistic white people were with their own kids and that they didn’t even recognize their children as children until the 16th century, while we were treating our children as gods, and sacred beings—and then how they modeled their treatment of black people on preexisting ideas and brutality against their own kids, and how this was implanted in our culture once we arrived [in the United Sates]; they’re open to that process.

You’ve also had pushback from people because you yourself are not a parent. What has that looked like, and how do you respond to that?

It’s been fierce. People say, “Well you don’t have kids.” And then I say, “Well, if I’m a doctor and I want to treat prostate cancer, should the requirement be that I have a prostate and cancer to do this?” I’m a member of the village; I’m like the auntie. Your children are going to encounter all kinds of adults in the village, and if being a parent is a prerequisite for talking about the treatment of children, then don’t listen to me. Listen to the thousands of parents who are investigated by child-protection services each year for abusing their kids.

I also say that I may not have children, but unlike a lot of people who do have them, I haven’t forgotten what it feels like to be a child. When people say, just wait until you have kids, it insinuates that once a woman has a child, there’s some kind of biological trigger that goes off in your body that now says: OK, hit kids. You know, this is a normal thing to do, to hit a child. So I look at the people who deploy that argument as folks that try to derail and shut down that conversation.

You obviously came to this work with a very personal perspective. Was there anything you discovered that challenged your beliefs?

No, it all confirmed my suspicions, particularly when I was delving into the science … For me, it was hard emotionally. I did not think that writing this book was going to test me emotionally the way it did. Because I’ve been talking about this issue for over a decade. But to sit on the phone and listen to people cry, particularly men, grown men who hadn’t had the space to talk about this issue, because black men talking about pain, particularly if it came at the hands of their mother, or grandmother or whatever, is considered a misogynistic act … When I watched the comedy—I spent two days just watching back-to-back comedy. These clips in isolation, people laugh at it. But when you look at the words, the things these men are saying about the treatment of their kids, it’s horrific. And I can never laugh at this stuff again.

Which parts in particular did you find the most challenging to write about?

The mothers beating their sons. That was hard. I wrote an article about that same subject before, and I got a lot of backlash for it. People were talking about how black women are blamed for everything. This is another thing that we, you know, do wrong. So there was this defensiveness, there was this need to defend black womanhood, to defend black mothers. And when we talk about black men’s misogyny and violence, it’s talked about like it’s something intuitive to their nature, [as if] socialization doesn’t play a part …

Sometimes, black men are groomed to be shitty toward women, because their mothers taught them how to be this way … Even some of the men I interviewed said, you know, I avoided black women altogether because of the way my mother and my aunties or grandma treated me. I thought all black women were mean, harsh. I didn’t want a woman who resembled anything like my mother. And when [black women] hear black men say this, it’s like, “Oh you just wanna be with Becky. You just want a white girl who’s going to do whatever.” It’s just dismissed. So that was a very, very tense chapter to get through.

I mean it’s a tricky line to walk, right? You talk in the book about the idea that we deify the black mother, often to the detriment of other black women. I can imagine that was very difficult to discuss.

Yeah, I’m bracing for the backlash on that.

Good luck! This whole book feels like a powder keg. Do you feel like the tide could be turning? Have you noticed a sizable shift in attitude since you started doing this research more than a decade ago?

What I’m still worried about is the data. … I’m still worried about the fact that every single year when I look at those child maltreatment reports—our kids are continuing to be abused at disproportionately high rates … I’m still disturbed that you can ride down South and look up on highway billboards and see things like, “spare not thy rod.” I’m still disturbed that 19 states, despite everything we know about the science … that thousands, that hundreds of thousands of kids each year are still being paddled in our schools.

But you know, in the 1980s, we started hearing people grappling with domestic violence against women. And that was just starting to be a conversation. These kinds of conversations that you and I are having, and that people are having on social media, that people had in the aftermath of the Adrian Peterson controversy, the Baltimore mom controversy—that was an international discussion over the beatings of black children. We just saw that in the past two years. And there’s more conversations about the science of corporal punishment. It’s becoming more mainstream. I think social media has really opened up the discussion much more. So I’m heartened by that.

Even with the pushback that I get, my thing is, you’re thinking about it. You’re angry with me right now because basically I’m telling you everything you’ve ever been told is a lie. Your momma was a lie; your preacher was a lie; everything was a lie. And that’s hard for people. It doesn’t mean your parents didn’t love you. But they were wrong for doing this to your body, and it’s probably impacted you in ways that will make you feel uncomfortable to think about it. I get it; I have empathy for that.