In New York a few weeks ago, Kim Brooks asked whether creativity and domesticity are compatible in women’s lives. The relationship between art and parenthood is an evergreen topic that makes everyone—male or female, artist or not—feel a little bit anxious, for reasons specific to their life circumstances. (“I’m a bad parent!” “I’m not creative enough!” “Maybe I shouldn’t have kids!” “Maybe I should!”) I’m no exception; as a child-curious writer, I read this last salvo as soon as I saw the link. Target audience, c’est moi.

But there was one paragraph in Brooks’ piece, about the terrible husbands and dads of literary history, that I relished with particular glee. These “art monsters,” as writer Jenny Offill memorably termed them in her 2014 book Dept. of Speculation, are sometimes women, but they are most often men. The constraints they rail against are female, either explicitly or implicitly: requests for time and attention, petitions for financial support, or expectations of conformation to social norms. To such demands, the art monsters react poorly. “Baudelaire longed for escape from ‘the unendurable pestering of the women I live with,’ ” Brooks writes. “Verlaine tried to light his wife on fire … Faulkner’s 12-year-old daughter once asked him not to drink on his birthday, and he refused, telling her, ‘No one remembers Shakespeare’s children.’ ”

I don’t think it’s (just) the fascination of voyeurism that makes these anecdotes so compelling. I believe it’s a salutary exercise to look back at the bad marriages of the art monsters (and politics monsters, and sports monsters, and war monsters, and finance monsters) whose names are so prominent in our historical record. Remembering how the worst among them treated the women in their lives is one way to see the invisible labor—women’s labor—that went into nourishing, cleaning, arranging, regulating, and picking up the pieces at every turn. Like white space around a striking image, this reproductive work takes squinting to see. The work of maintaining is much less glamorous than the work of making, and leaves fewer traces. With this in mind, I propose the Historical Theory of the Bad Husband: as a good a way as any to see what’s hidden.

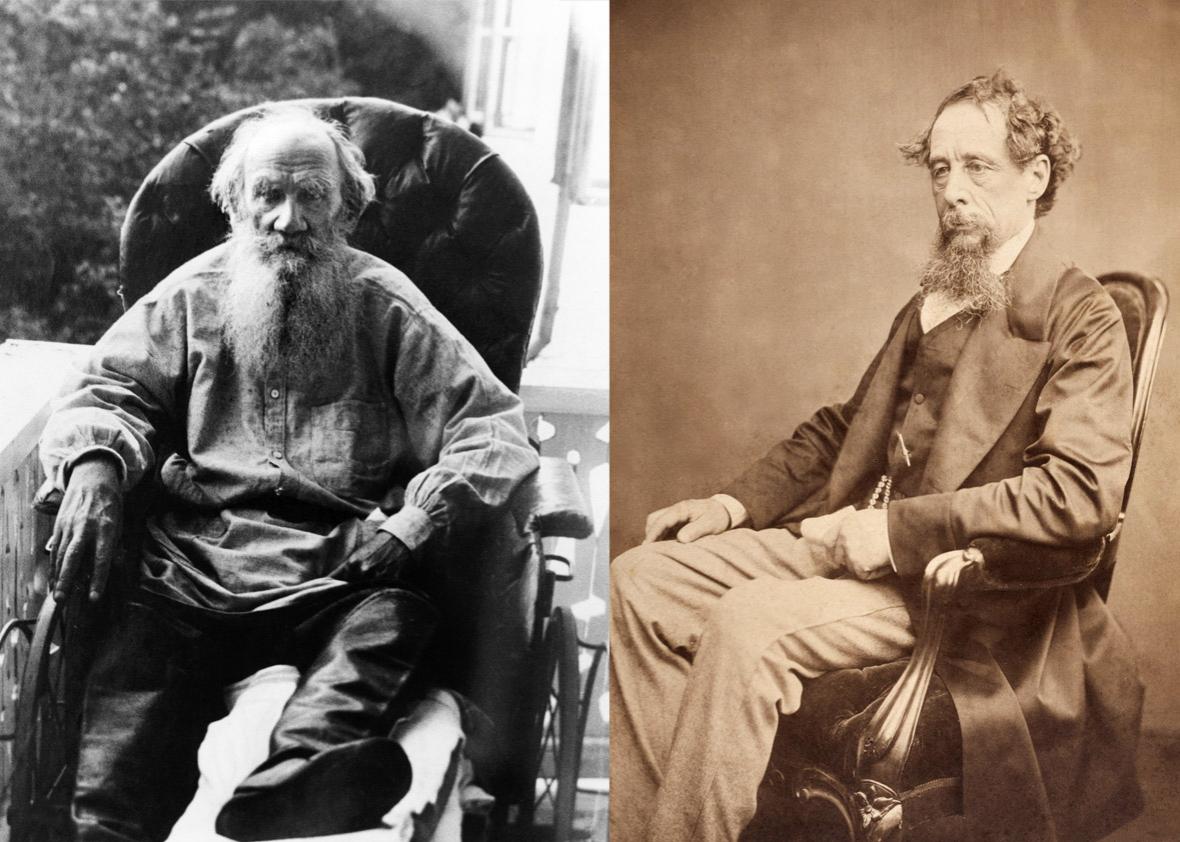

Often the debate over whether we should condemn someone like Leo Tolstoy—who refused to consider giving his wife a rest from her constant pregnancies, or to help her much with the resulting babies—centers around whether or not the person in question was “typical of his time.” Tolstoy’s wife Sofia almost died when she contracted puerperal fever after her fifth delivery, but he impregnated her again and again. He also made her breast-feed, even though it was extremely painful for her.

Tolstoy made his wife’s life a misery because of his own ideas about gender: “It was not just that Tolstoy could not conceive of marriage without children,” writes his biographer Rosamund Bartlett. “He regarded a woman’s main vocation as being to bear children, breast-feed and raise them, and was therefore horrified at the thought of his wife avoiding future pregnancies.” For her part, Sofia, who eventually had 13 children total, wrote in her diary in 1870: “With every child you have to give up a life for yourself even more, and resign yourself to the burden of cares, worries, illnesses and years.”

Tolstoy’s apparent disinterest in his wife’s reproductive desires might not have been strange to 19th-century onlookers, but it’s that very fact that would make the Tolstoy story an instructive lecture in my college course on Bad Husbands in History. Sofia Tolstoy’s reproductive labor was both physical (13 pregnancies! I’m exhausted) and mental. The social privileges that let Tolstoy’s work blossom had their inverse in Sofia.

Likewise, Charles Dickens’ treatment of his first wife, the former Catherine Hogarth, whom he dumped for a teenager after Catherine bore him 10 children, shows how the social power of men (especially wealthy and famous men) in 19th-century England created a dangerous imbalance that could strand women who fell on the wrong side of the line. Catherine, who Dickens spoke of publicly as fat, boring, ugly, and insane, ended up separated from her children and alienated from several of her own sisters before the charismatic and famous Charles was done with her. That Catherine’s “insanity” might have been due to successive bouts of postpartum depression is all too ironic.

The Dickens-Catherine affair aligns with several other historical instances of wives who were set aside when younger or more appealing models came along. The wives of Henry VIII, Emma Hale Smith, and the first two spouses of Donald Trump might offer Catherine some sympathetic company. Latter-day (male) commentators often wink at the proclivity of powerful historical figures to take on a series of younger and younger wives; the author of this Bleacher Report slideshow on bad husbands in history (I know) appears to outright admire such men. But I’d like to set aside my outrage at individual cases to think about the larger meaning of all those discarded wives. If male power has always left middle-aged women tossed aside in its wake, aren’t the lives of those middle-aged women part of the story of their achievements?

Even historical traces left by men who were not complete monsters can be instructive in our quest to see all the everyday work that went into the production of genius. In 1914, when Albert Einstein wanted out of his first marriage with fellow physicist Mileva Marić, he gave her an amazing list of conditions she would have to agree to for them to stay together. It doesn’t sound like a good deal: Mileva would have to serve him three meals regularly in his room, ensure that his laundry was done, and keep his desk clear. But it’s the emotional requests that seem especially harsh. In order to preserve the marriage, Mileva would have to require literally nothing from Einstein by way of support or understanding. “You will not expect any intimacy from me, nor will you reproach me in any way,” he wrote. “You will stop talking to me if I request it; you will leave my bedroom or study immediately without protest if I request it.” This strained and cold domestic life, which Mileva initially agreed to, was short-lived, but in Einstein’s requests you can see how little he felt like he needed to extend to her, in exchange for the domestic arrangements he wanted to continue to enjoy. (I must note, for Albert’s sake, that after they divorced he did support Mileva and their two sons financially for the rest of their lives.)

I often look at “women’s history,” as it’s commemorated in March of every year—the nods to a few women who managed to succeed in a “man’s world,” to overcome censure and barriers in order to innovate or create or write or fight—and wish for an alternate history of the women whose names won’t be known. The ones who changed the diapers, swept the floors, and openly seethed when their monster husbands or boyfriends decided a road trip sounded like more fun than work. Show me your wet blankets, nags, and shrews; I’ll show you the essential grease that made the wheels turn.