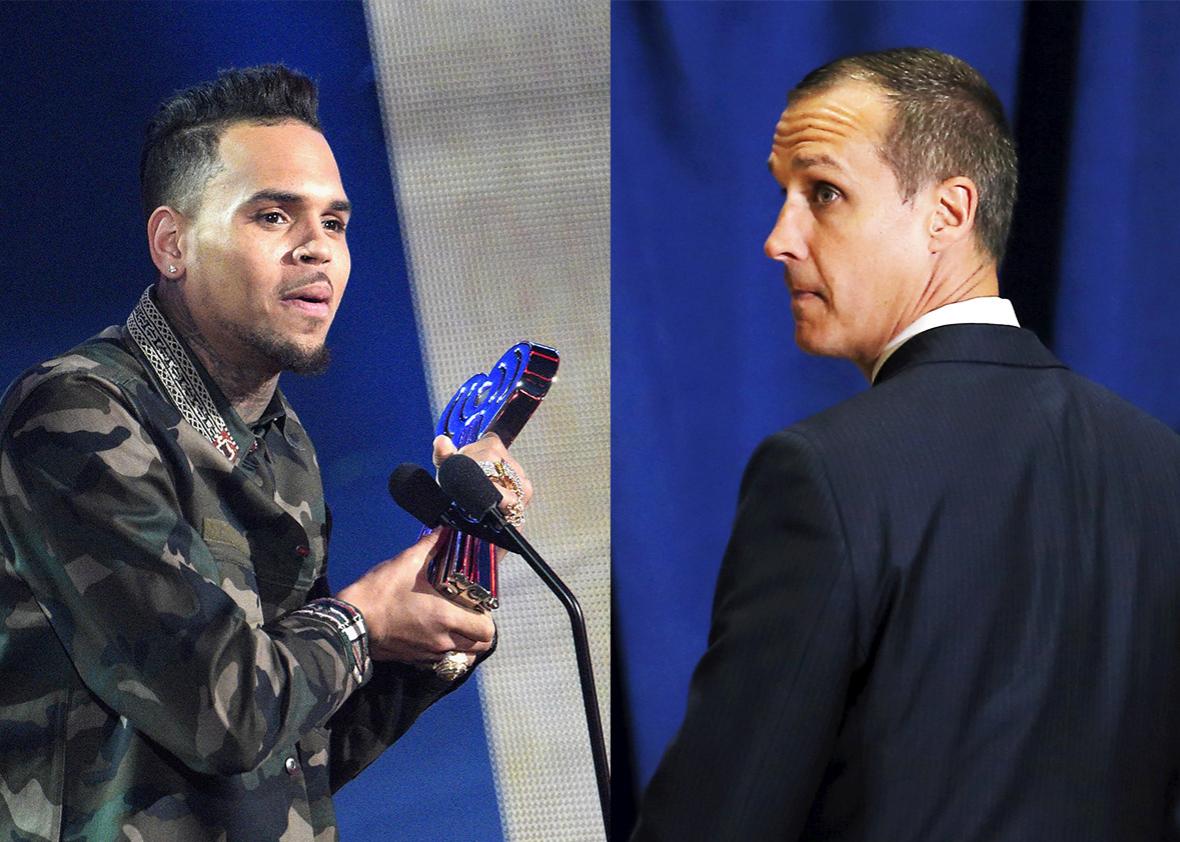

Last month, Donald Trump’s campaign manager Corey Lewandowski tweeted that Michelle Fields, the reporter whom he was caught on tape grabbing and forcibly moving away from Trump, was simply “an attention-seeker.” Last week, Chris Brown called fellow R&B singer Kehlani’s suicide attempt a fake, telling her to “stop flexing for the [Insta]gram.” Commenters on Twitter fell in line, calling Fields “an attention seeking liar” and Kehlani “your average attention-seeking female.”

In the past couple of years, the “attention-seeking” label has become an all-purpose way to gaslight feminists, silence those who demand restitution for a specific wrong, and shame women for the way they present their bodies and selves in public. “Attention-seeking” has DNA in common with reductive jokes about women with “daddy issues”; it draws from centuries-old hatred for women who demand to be heard and from some men’s deep resentment of women’s physical attractiveness. But social media, which has initiated a new culturewide conversation about what is public and what is private, has made “attention-seeking” the misogynist stereotype du jour.

When used to address a woman who wishes to bear testimony or present an analysis, “attention-seeking” sweeps every merit of her truth or observation away in a profoundly ad hominem accusation, lent even more weight by its gender essentialism. In 2014, Ann Coulter appeared on conservative talk radio host Lars Larson’s show to talk about that year’s disastrous Rolling Stone cover story about a campus rape at the University of Virginia, a story later found to have no basis in reality. Besides saying that rapes are only rapes if the woman has been “hit in the head with a brick” during the assault, Coulter suggested that women who come forward about being raped are “girls trying to get attention.” The disgust and dismissal in that statement—Coulter also mentioned Lena Dunham, boogeywoman of the right—show how “attention-seeking” infantilizes the person who’s hit with the label.

When applied to rape victims, “attention-seeking” doesn’t just disavow any truth in the accusation; it represents the woman in question as not so much evil as pathetic. Fantasy writer (and misogynist) Vox Day wrote in 2014, “This was the inevitable result of creating St. Rape Victim, now every attention-seeking young woman wants to have been raped”; a commenter added, “It’s a sad state of affairs when women have to resort to these tactics to get attention. And even more sad state when they are the ones who put themselves there in the first place by embracing everything that makes them unattractive to men.” Day’s commenter put his finger on an implication hidden deep within the “attention-seeking” label: the idea that women could get attention from men the “right” way, if they knew how; the “attention-seeker” has just chosen the wrong way to handle the game of gender.

In BuzzFeed last week, Joseph Bernstein reported that right-wing tech journalist Milo Yiannopoulos maintains a stable of “mostly unpaid personal interns” who write his posts for Breitbart.com. Bernstein quotes Yiannopoulos’ instructions to a group writing “a speech about feminism”: “Include 1) feminism attention seeking for ugly people 2) wage gap 3) campus rape culture… a load of mean jokes.” That first talking point is key: Feminists have only resorted to feminism because they can’t “get attention” any other way.

However, being conventionally attractive to heterosexual men, and receiving their sexual attention accordingly, is not enough to exempt a woman from being called “attention-seeking.” When used to address a woman who dresses provocatively and displays her body online, “attention-seeking” blames the women for every bit of the patriarchal culture that wants to see young women unclothed and that assigns her power based solely on her body.

Take the obsession with Ayesha Curry, wife of unbelievably good basketball player Steph, whose devoted housewifery and motherhood have (as Damon Young of VerySmartBrothas writes) made her into a convenient stick Internet misogynists now use to measure and judge women who get out of line. One Ayesha meme juxtaposed Kim Kardashian’s most recent nude selfie with a smiling photo of Ayesha, holding her two children; the meme accumulated a number of different captions, but here’s one: “There’s two types of baby mamas/wifey…Choose wisely!”

Onsizzle

The Kim vs. Ayesha contrast is useful to see the way “attention-seeking” can be used to indicate a woman whose online image feels, to men, to be “wrong” or inauthentic. Of course, Ayesha has an image, too; she has constructed a pretty great online brand. (She just got a show on the Food Network, and surely that wouldn’t have happened without the work she’s been doing to promote herself and her cooking on social media.) The “attention” Ayesha gets feels “correct” to the men who hail her as the best kind of “wifey”; the “attention” Kim gets feels like it’s been extorted from them, and they respond by labeling it pathological.

The “attention” question rules our conversation about women and social media. Reviewing Nancy Jo Sales’ new book, American Girls, about social media and teenage girls in the New Republic, Elspeth Reeve observes that the word “attention” is omnipresent in the text: “repeated again and again by the author, her experts, her teen girl subjects, and their internet harassers.” The word, Reeve writes, “is delivered as both a diagnosis and an indictment,” a bit of common wisdom about girls’ relationships with social media. “In Sales’ book,” Reeve writes, “it is something only girls want.” And “attention” means something different when applied to boys and to girls:

When boys [look for attention] it’s charming; when girls do it, it’s corrosive. Men are supposed to strive, women are supposed to be discovered; men are expected to seek the admiration of their peers, be entrepreneurial and adventurous; women are expected to do all the required reading and homework and hope someday someone notices their diligent competence.

The desire to be known—to be paid mind—is profoundly human. As neuroscientist Billi Gordon writes on Psychology Today, “Without getting and giving attention, you could not have a social species. Getting attention is necessary for life’s vital enterprises, and can be the difference between life and death in a crisis.” For most women, “attention-seeking” is simply … living. The much smaller number of women who may have a relationship to attention that’s been disordered by early trauma should be helped, not mocked.

But here’s the most galling thing about “attention-seeking” as an accusation: The very idea that “attention-seeking” is a specifically female quality is hilarious, when you look at the sweep of human history. Who, pray tell, is more attention-seeking than men?