I first heard of what’s known as the 10-step Korean skin care routine when my colleague Dorothy Kim, a professor of medieval literature at Vassar College, sent me a stack of peculiar-looking sheet masks along with some baby clothes her son had grown out of. “What the hell are these?” I asked. “I mean, thank you.” The packets—with names like Bling Bling Hydro Gel Mask and Ferment Snail—were, as Kim explained, the “gateway” product into a complex and time-intensive beauty regimen that South Korean women have been practicing religiously for years.

“They make you look like a serial killer,” Kim warned, “but they’re ultra-moisturizing, and you can wear one while you’re breastfeeding!” So, whenever I happen to find 15 luxurious minutes to myself, I slapped one on. The change to my skin was instantaneous: My face felt more elastic, firmer, smoother, like it could breathe. It was as if I’d been a Korean beauty—or K-beauty—devotee my entire life but just hadn’t realized it until I was properly moisturized.

Once I admitted to Kim that I enjoyed “masking,” that was it. In the next box of baby stuff came a dozen different vials of goop, all of which had to be applied (and sometimes un-applied) in a precise order. Not one, but two cleansers—and the first, an oil “cleanser,” felt so wrong to someone raised on the tingle of Noxzema—followed by a “toner” that felt nothing like Sea Breeze; then an “essence,” a thin goop of something that I still haven’t figured out; thereinafter, a serum that is basically an even gloppier essence; then the serial-killer mask; followed by an eye cream—and, at long last, multiple “emulsions,” or moisturizers. (Read a legitimate rundown of the routine here. It’s not always 10 steps. Sometimes it’s more.)

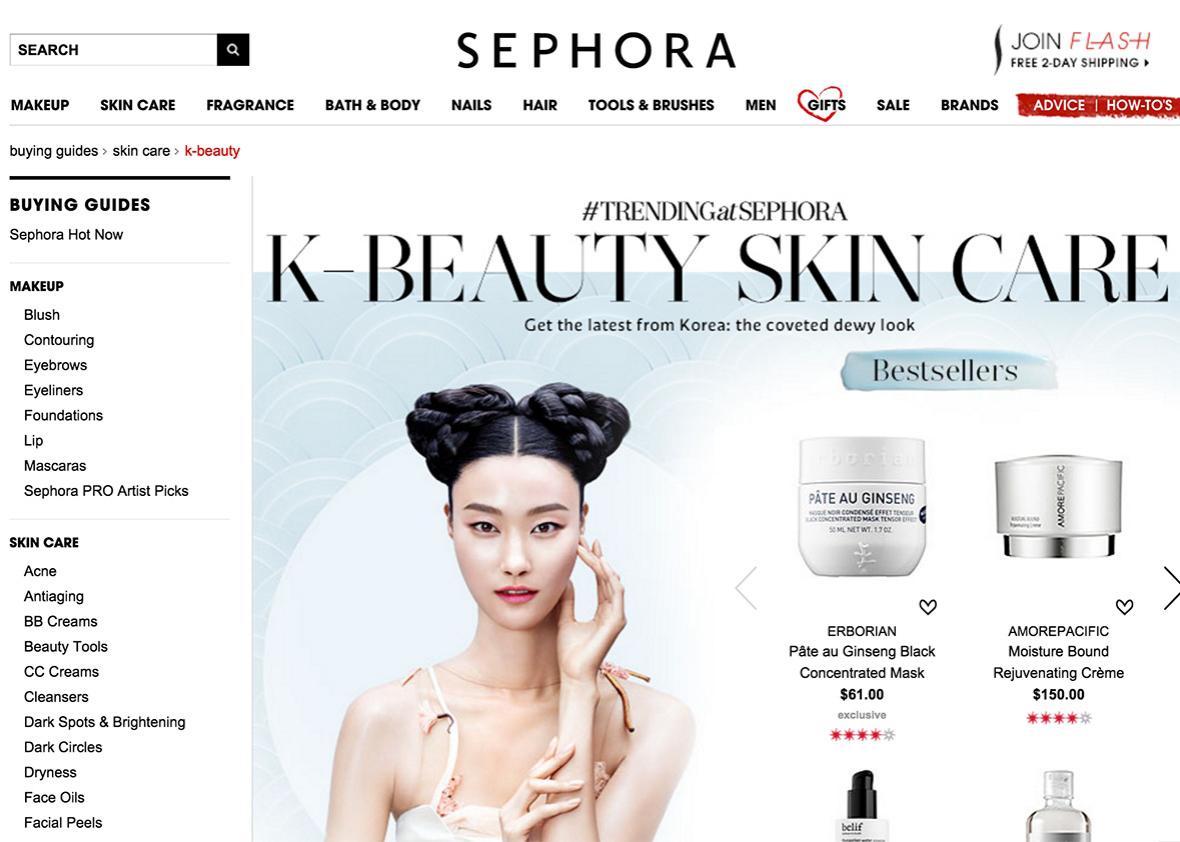

My visage had taken a beating from pregnancy and then another from the abject neglect resulting from new motherhood; now, it was honest-to-goodness “dewy.” I started looking askance at friends who “only” used a cleanser and moisturizer. I wondered why K-beauty wasn’t already a massive stateside trend—and then I stopped wondering, because it is a massive Stateside trend, and has been for a while. (The only reason I didn’t realize this is that I am a decrepit loser, who until very recently thought I could use the phrase Netflix and chill to describe binge-watching Making a Murderer while the baby napped in my arms.) You can buy three-packs of sheet masks imported directly from Seoul at Rite Aid. The Sephora website has an entire K-beauty section. Birchbox now regularly includes Korean products in their monthly subscription boxes and recently launched a K-beauty specialty box. Charlotte Cho, one of the beauty pioneers credited with popularizing K-beauty in the U.S., writes a column for Elle.

What I didn’t realize until recently, however, is that K-beauty is also popular with self-identified feminist academics and scholars, several of whom told me that they view the elaborate routine not as vanity but rather as an act of radical feminist self-care.* Indeed, Stockton University English and digital humanities professor and Web designer Adeline Koh published an entire blog post on the subject. She wrote:

I’ve started to view beauty as a form of self-care, instead of a patriarchal trap. One of my deepest inspirations, the writer and activist Audre Lorde, famously declared that “Caring for myself is not self-indulgence, it is self-preservation, and that is an act of political warfare.” For many women, especially women of color, we’re often told that we are only useful, only valuable when we devote ourselves to others; that caring for ourselves in the last thing that we should consider.

Kim agrees. “Self-care, especially for a woman of color, is radical,” she tells me. Korean beauty “is a little breath of relaxing joy and feminist community.” She explains that this may also stem from the centuries-old tradition of spa and self-care in Korean culture. Kim emphasizes that “the Korean spa is also primarily about relaxing with other women and hanging out, rather than just ‘go to the spa, get these things done to you, leave.’ It’s frequently a family affair. I remember going to the Korean spa with my cousins and aunts in Korea when I used to visit.”

Indeed, for many of the women I interviewed, the Korean routine is not merely about results (although they are certainly happy about the results). Instead, similar to the Korean spa experience itself, it’s also about the ritual: the precise order of layering; the time necessary to let essence or serum penetrate before the next product can be applied; the special patting motion for the eye cream, etc. This particular form of self-care can be empowering for women (such as myself!) who are well outside of the age range considered sexually attractive (at least by DiCaprio standards). Katharine Jager, a medievalist and mother of twins, tells me, “The world is not kind to middle-aged women who are mothers, even if we are highly educated college professors. So we had better take care of ourselves.” Indeed, thanks to the routine’s emphasis on ritual and patience, says Jager, she not only has beautiful skin; she also has “less tolerance for bullshit” all around. (And to think, sheet masks are usually less than $3.)

I can’t speak for Jager’s personal “bullshit” factor, but I can verify that, in my experience at least, female academics often walk a very peculiar line in The Profession. Despite being surrounded by allegedly forward-thinking individuals, they are still expected to look “polished and presentable,” as Kim puts it, and “yet never discuss the time and effort it requires to be so.” This is especially true on the ever-fraught job market, on which Koh (who has tenure and thus navigated it successfully), quips that “female candidates are often encouraged to look as asexual as possible to be ‘hireable.’ ” But also polished. But not too polished. Simple, right?

Part of why K-beauty in particular seems to have trended in academia is that it’s gentler and often less expensive than the other methods popular in the U.S.—bizarre vibrating-brush contraptions; facials; shoving needles into ourselves. But another reason is that the K-beauty routine can be blended fairly seamlessly with a solitary, writing-intensive profession. More than one scholar I interviewed reported dividing writing or grading goals into mask units. Several plan to incorporate group masking into informal meetings at this weekend’s Modern Languages Association conference (which makes the whole experience sound a tad less odious).

It even intersects with some scholarship—for example, Koh’s current book project, which is “a comparative study of representations of whiteness in different parts of the world.” Skin care trends fit into this research, she says, ”especially in terms of the more problematic issues of race and colorism.” For example, “Korean beauty products often sell themselves as ‘whitening,’ which makes people in the U.S. think that they are bleaching their skin. The ingredients they use are never very extreme,” she assures me, “but they do even one’s skin tone, eventually making one fairer. American products use the same ingredients but sell them using completely different language.” This makes for some awkward translations, though—such as the Korean brand with a product called White Power Essence. “American users pointed out the racial dynamics here, and the company is reconsidering the name,” she says.

At the moment, Koh is on sabbatical, and she’s moved on from research to praxis. She started formulating her own Korean-inspired skin care products because she found that commercial products sometimes irritated her skin, and she found the actual presence of much-touted active ingredients (like the decidedly not-vegan snail mucin or donkey milk) to be too small. She treated the formulation of her own products like another research project, studying cosmetic science textbooks and testing all products on herself (!). “I’m actually making something physical, which is quite different from my academic work where I work on ideas,” she says. Once her friends started seeing her skin, they pulled a Newman’s Own on her and demanded some for themselves—so now she’s gone commercial. Her company, the aptly-named Sabbatical Beauty, regularly sells out of products with highbrow referential names like Dorian Gray’s Anti-Aging Serum. (I can only hope there’s also a Painting in the Attic Pro-Aging concoction as well.)

While the “radical self-care” of K-beauty may just seem like an interesting hobby these academics have picked up—and the ensuing “community of feminist scholars,” as musicology professor Elizabeth Randell Upton put it, merely a pleasant side effect— it may also have serious positive effects in a profession with sometimes startlingly high rates of depression. Beauty blogger Jude Chao, for example, writes here about how her own experience with K-beauty helped her fight depression; she is delighted with the results on her skin, yes, but also lauds the routine’s ability to ground her in her skin, her body, “and—not to get too New Age-y—the present.” The present, she says, is what depression “snatches” from her; it “makes all the days blend together.” The Korean skin care ritual, she says, “gives the present back to me twice a day, every day.”

So if you’re a college student and you happen to surprise your ethics professor in her office and she’s decked out like Jason, don’t be alarmed—and don’t dismiss her as vain. She’s engaged in a political act of self-care and/or unwinding from the day’s “bullshit.” She might even be keeping her mental health intact while giving your latest essay precisely the correct amount of grading time.

*Correction, Jan. 7, 2015: This article originally misidentified the bloggers Tracy of fanserviced-b and Cat Cactus of Snow White and the Asian Pear as “self-identified feminist academics and scholars.” Neither blogger self-identifies as a feminist, and Cat Cactus is not an academic. The piece also stated that Tracy and Cat Cactus are among women who “view the elaborate [K-beauty] routine not as vanity but rather as an act of radical feminist self-care.” Both bloggers disavow this view, and neither of them were contacted for the piece. (Return.)