In this series, Double X writers look back on 2015’s flashpoint debates around gender and feminism as they played out in the spheres of reproductive rights, work-life balance, pop music, affirmative consent on campus, and more. Read all the entries here.

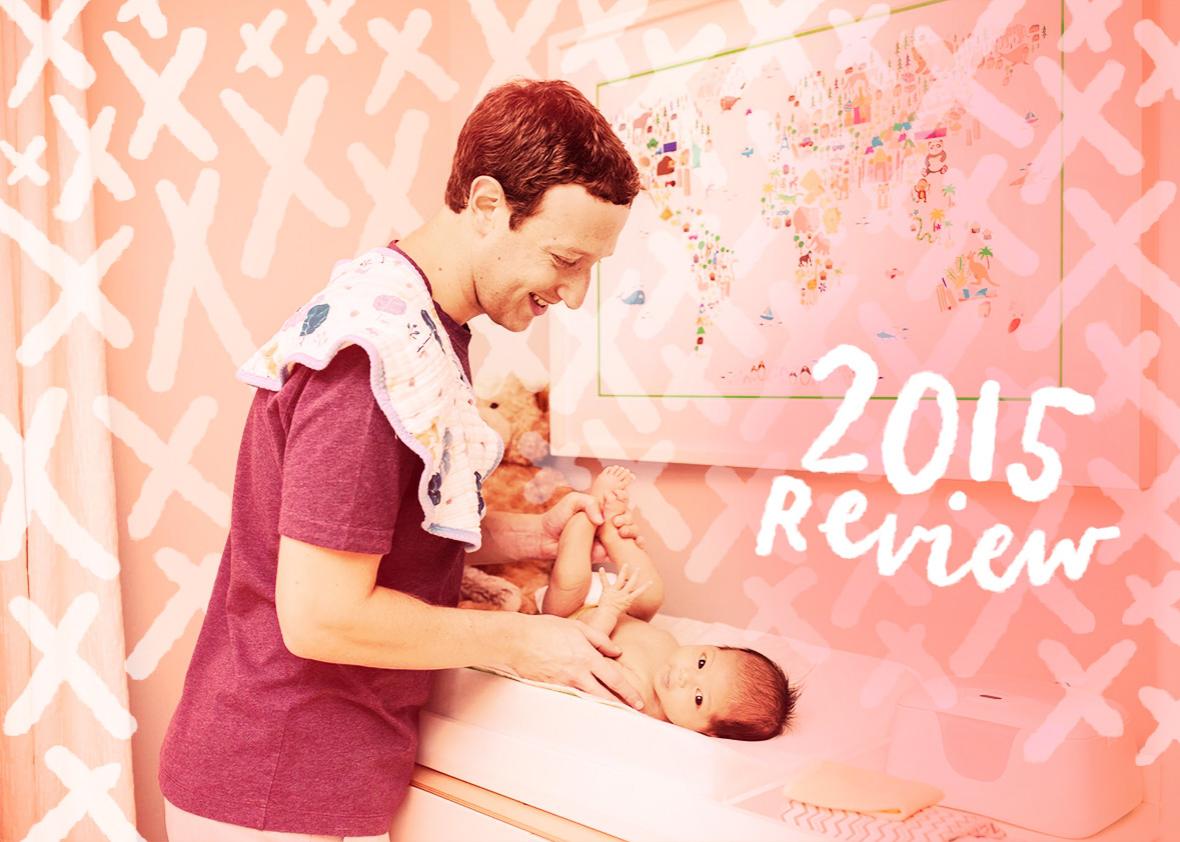

In November, Mark Zuckerberg made one of the most universally applauded decisions of his career: He announced that he’d be taking two months of paternity leave to stay home with his baby daughter, Max. As Wired noted at the time, Zuckerberg is “perhaps the most prominent chief executive of a major public tech company to take this much time off following the birth of his child.” His choice, in other words, sets an unprecedented example for men.

If the Facebook founder is acting from a new script, it’s one that he had help writing in 2015. This year, Silicon Valley’s biggest battle was the competition to come up with the best parental leave—not maternity leave—policy. The most-buzzed book about working life was Anne Marie Slaughter’s Unfinished Business, an exhortation to Americans to place more value on caregiving. As the enthusiasm over Zuckerberg’s announcement suggests, American culture seems to be in the process of inventing a new kind of leading man: one who approaches work, and work-life balance, more like a woman.

Netflix jump-started this conversation in August, when it announced “unlimited maternity and paternity leave” for certain employees within the first year of a birth or adoption. Within a week, Microsoft and Adobe had also upped their policies. The wave ultimately swept beyond Silicon Valley. Amazon plumped up its parental leave policy following a scathing New York Times piece. Goldman Sachs doubled its paid paternity leave (from two weeks to four). The investment firm KKR announced that it would start paying for a nanny to accompany new parents traveling on business.

It’s not enough, of course, for companies to offer paternity leave; men have to take it. In a May piece for Slate, Bryce Covert argued that paid paternity leave “could do an inordinate amount to shift culture and how we see working fathers”—and thereby demolish the notion that it’s only working mothers who could benefit from paid parental leave and flexible working hours. More recently, Helaine Olen wrote about a National Bureau of Economic Research study showing that men are more likely to take paternity leave for a firstborn child than any of the kids to follow—and, more vexingly, more likely to take more time for a newborn son than a daughter. Steven Weiss declared in the Los Angeles Times that “most Millennial dads are hypocrites” when it comes to co-parenting and work-life balance. He ended his piece by pleading with dads to “lean out.”

This shift in this conversation comes after decades of paying homage to the notion that women need to work more like men. As myriad studies have shown, assertiveness and ambition help men to advance but are often perceived negatively in women. (The Ellen Pao trial, and her subsequent resignation from Reddit, may provide a cautionary tale in this regard.) Encouraging women to act like men also hasn’t closed the gender pay gap, which is still estimated at about 22 cents per dollar nationwide. (In fact, the World Economic Forum recently calculated that it will take another 118 years to close the wage gap at the current rate.) This fall, the city of Boston started offering women free salary-negotiating lessons—but experts say that because colleagues don’t always respond well to women who advocate for themselves, banning negotiations altogether may be a better way to make workplaces more equitable. This idea squares with the observations in Jennifer Lawrence’s viral essay about discovering she’d been paid less than her male American Hustle co-stars. “[A]nother leaked Sony email revealed a producer referring to a fellow lead actress in a negotiation as a ‘spoiled brat.’ For some reason, I just can’t picture someone saying that about a man,” Lawrence wrote.

If emulating successful-male stereotypes can be a dangerous proposition for women in the workplace, so, too, is acting stereotypically “feminine.” Acknowledging the pull of parenthood and other traditionally female caregiving roles can be risky even when women are in positions of power, as Katharine Zaleski revealed in March when she spilled her guts in Fortune about the way she used to discriminate against working mothers. Zaleski is now the co-founder of a new company called PowerToFly, which matches women with positions they can do from home.

In prioritizing flexibility, Zaleski is clearly onto something: A recent study shows that the majority of women who start businesses in the U.S. do so “to tailor their work to their family needs,” writes Quartz. (Since these enterprises usually stay small, this trend may actually be hurting the economy’s growth—just one more reason to combat workplace sexism.) But Zaleski’s pitch—that moms make extra-great employees—is frustrating for relying on the assumption that women are the default caregivers and house-runners: “Moms work hard to meet deadlines because they have a powerful motivation—they want to be sure they can make dinner, pick a child up from school, and yes, get to the gym for themselves,” she writes. Rather than singling out moms for praise or penalties, it would be great if Zaleski—and the rest of America—could simply devise professional cultures where women can work as effectively as men, and for equal compensation and respect.

This is the simple-but-radical hope behind Slaughter’s Unfinished Business, which improves on Zaleski’s framing; Slaughter wants to overcome the gender paradigm by raising the status of caretaking responsibilities that we currently perceive as standing in women’s way. Right now, Slaughter suggests, we devalue these roles because they fall to women, and they fall to women because we devalue them. But what if we could reverse the cycle? Slaughter writes:

Most of the pervasive gender inequalities in our society—for both men and women—cannot be fixed unless men have the same range of choices in mixing caregiving and breadwinning that women do. To make those choices real, however, men will have to be respected and rewarded for making them: for choosing to be a lead parent; to defer a promotion or work part-time or spend more time with their children, their parents, or other loved ones; to take paternity leave or to ask for flexible work hours; to reject a culture of workaholism and relentless face time.

If men did more caregiving, it would free women up to do more breadwinning. If men dignified caregiving with more of their labor—just as a certain billionaire is by changing his baby girl’s diapers—women might finally feel the stigma around balancing work and life dissolve. In other words, if men tried to conduct themselves more like women in the workplace, the archaic divisions between men’s work and women’s work might finally erode.