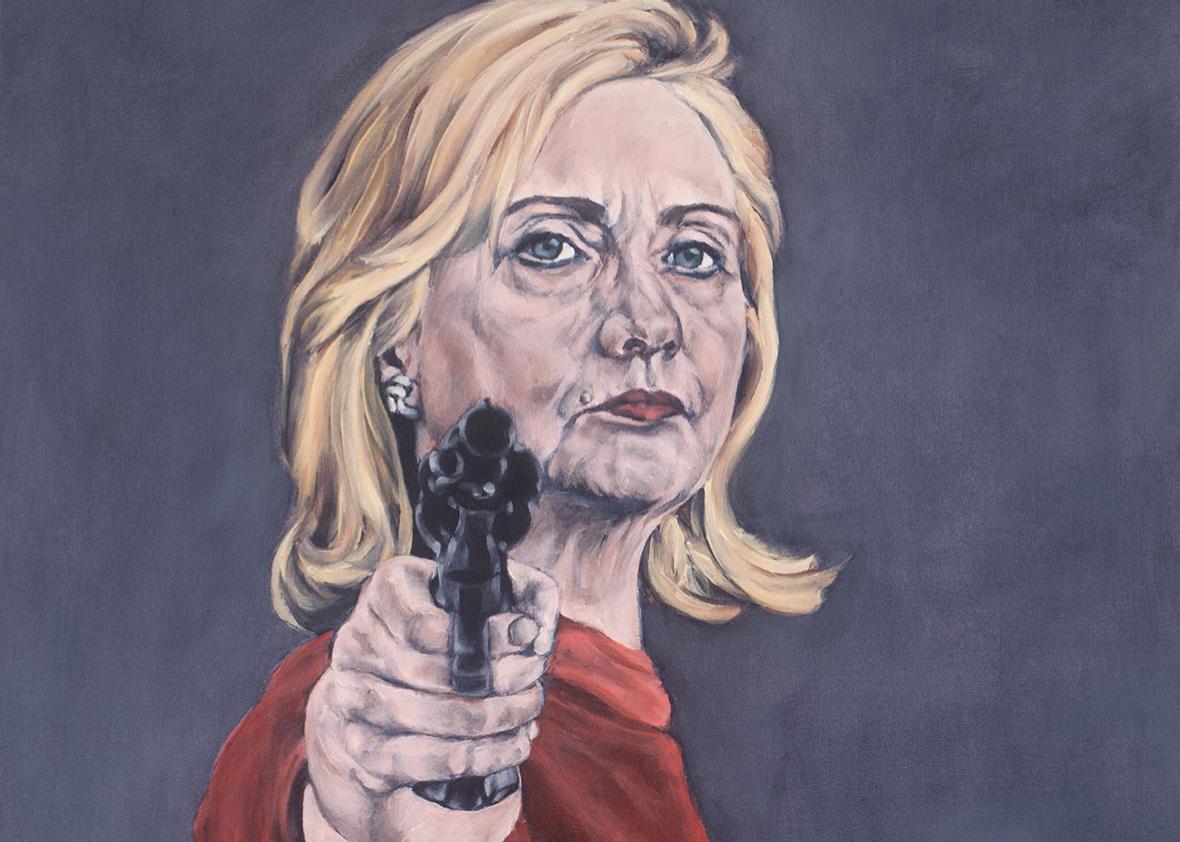

Hillary Clinton is uniquely able to divide sentiments on the political left. The center of the controversy this time is an unusual image: a painting of Clinton armed with a gun, which is pointed straight at the viewer, and a pitiless expression. It appears on the cover of a new book about the former secretary of state’s career.

The contents of this book—which is titled My Turn and written by perhaps the most notoriously anti-Clinton lefty, Nation contributor Doug Henwood—undoubtedly influenced the cover’s reception. Salon’s Joan Walsh called it “disgusting”; Salon’s Amanda Marcotte tweeted wryly, “I keep hearing it’s unfair to think that some of the male Clinton haters on the left might have issues with women.” Other feminist commentators had more favorable reactions to the cover—like Notorious RBG co-author Irin Carmon, who tweeted, “Wow the @HillaryClinton campaign is really going next level in portraying her as a badass.”

This last interpretation comes closest to the original intentions of the painter, Sarah Sole, who tells me that she’s “drawn” to Clinton. “She’s got this larger-than-life physicality about her,” Sole said in a phone conversation from her home in Stony Brook, New York, “and this butch demeanor embodied in an incredibly female form.”

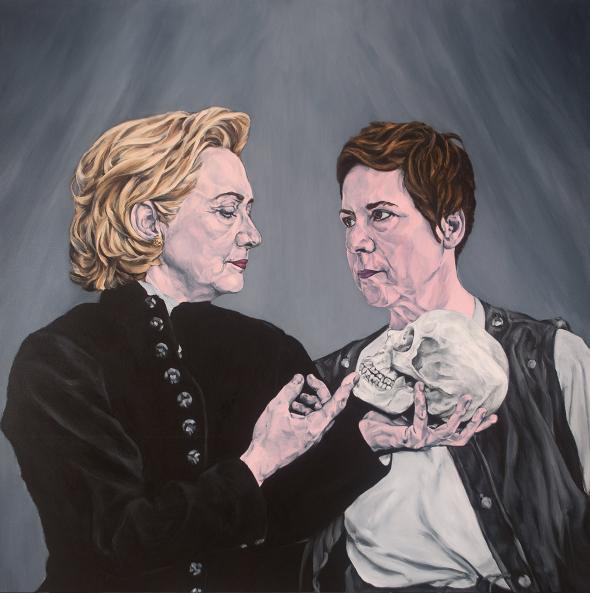

Sole has spent a lot of time ruminating on that form. She left her first career as a mathematician to pursue her love of visual art in the mid-2000s. She was getting an MFA at the School of Visual Arts in New York when Clinton first ran for president eight years ago. “In May of 2007, I became kind of obsessed with her,” she says. “Those were my first paintings. I was learning how to paint—poor thing,” she laughs. Since then, Clinton has remained Sole’s primary subject, and has figured in dozens of her works. Sometimes, Sole herself is in there, too—locking lips with Clinton, or getting married to her, or performing Hamlet with her.

Image by sarah-sole.com

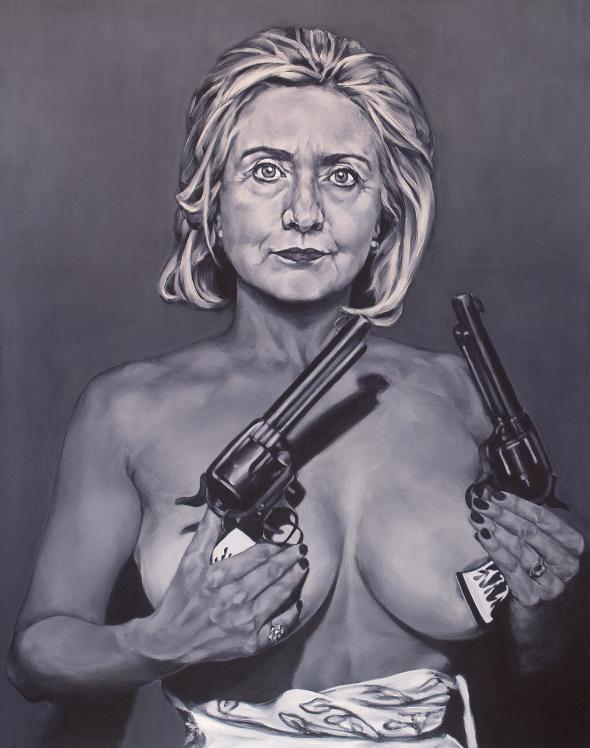

The painting Henwood chose for his cover is far from the most racy. Sole, who is intrigued by the aesthetic of the 1950s—the image with the gun was based on a famous photo of 50s movie star Natalie Wood—has painted Clinton’s face onto the scantily clad figures of pin-up girls and on the bare torso of the exotic dancer Tempest Storm. In one less sexual but even more inscrutable image, Clinton is a Teletubby (or, according to the painting’s title, TeleHilly). About one busty image based on a Richard Avedon photo of Elizabeth Taylor, Sole says, “I set out to make a beautiful Hillary.” To her, these images are less subversive than celebratory.

Image by sarah-sole.com

So how did Sole’s pulpy homage to Clinton end up on the cover of an anti-Clinton diatribe? She and Henwood met on Facebook; she listens to his radio show, Behind the News. She told me she was aware of their vast difference in opinion about Clinton when she agreed to let him use her painting for his book cover—though how aware, it’s not entirely clear. Henwood’s book is based on a Harper’s magazine story he wrote in 2014 called “Stop Hillary!” “I hate to say it, but I couldn’t get through the Harper’s piece,” Sole told me. She devoured some of the anti-Clinton literature that came out in the 1990s—“They’re packed with all kinds of sexy stuff. I thought, ‘If any of this stuff is true, I love this woman!’ ”—but Henwood’s argument, which focuses on what he sees as Clinton’s inconsistency and her “broad fealty to the status quo,” “is boring to me. I like the more salacious stuff,” Sole says. She sees the book and its cover as “the hybrid of two imaginations not in agreement on what they see in Hillary.”

Some critics of the cover have pointed out that, even if Sole intended the image to be sexy and powerful, in the context of a book that lambasts Clinton’s hawkishness and ambition, it plays into the stereotype that any woman who wields force is cartoonishly unnatural, a villain. “I’m hyper-feminist,” Sole told me, unconcerned. “I see an embrace of Hillary aesthetically as an incredible feminist statement.” Though she likes to mash Clinton with images of traditionally “perfect” female bodies, she says, “I don’t hyper-eroticize her or cosmetically correct her. I love the signature folds of her face; I love the animation of her eyes.” Compare this, she says, to models with “no hips.” “The fertility, that big human mass of Hillary, is so scary to us.”

In fact, Sole describes her fascination with Clinton as “libidinal.” It began in 2007 as a “salacious” dream.” The work that’s followed is “about drive,” she says, “whether that’s sex drive or ambition, aspiration, longing. It’s about an unmet drive.” Now, she says, she desperately wants Clinton to be president, but she’s not sure what that will mean for her art. She described the campaign as “the longest foreplay ever”—a person who is running for office, making promises, is “pure potential, and how sexy is that?” It certainly speaks to the unique energy of Clinton’s long pursuit of the presidency that it has produced not only Henwood’s book and Sole’s oeuvre, but also the highly unlikely marriage between the two. What comes next, no one knows—but Sole says she’s lately found herself painting her own image front and center in her pieces, relegating Clinton more and more to the background. “What I really wonder,” she says, “is does she become president, and I completely lose interest?”