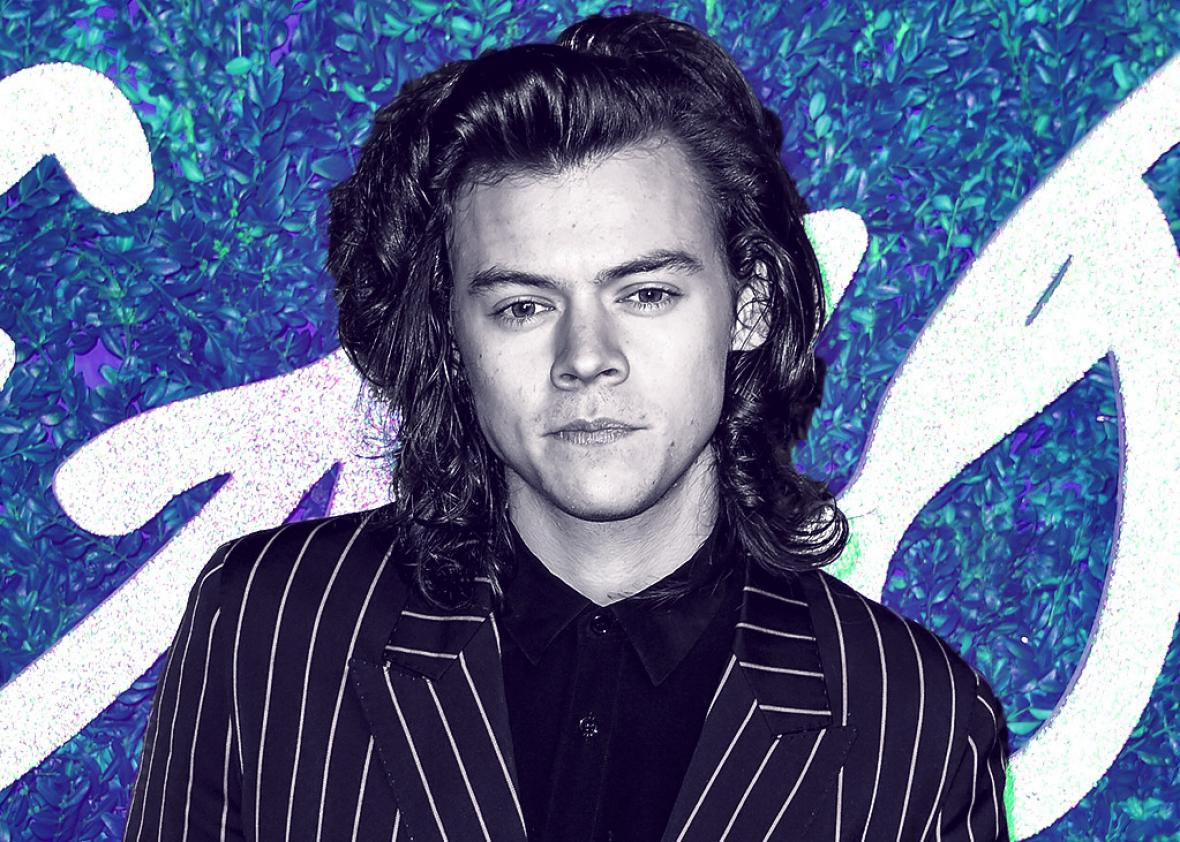

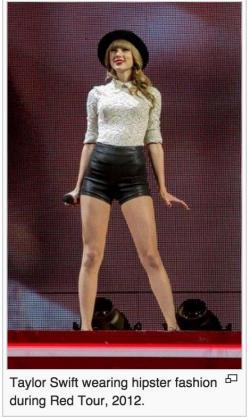

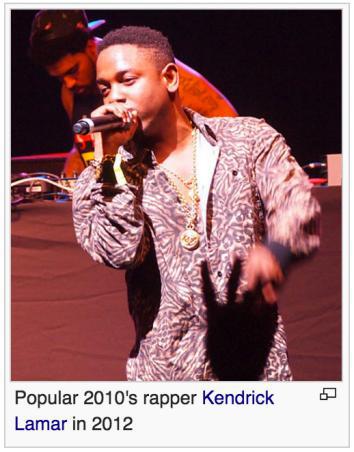

If you skim the Wikipedia entry for “2010s in Fashion,” you’ll learn a great deal, both about passing fancies and lasting trends. “Neon colors and elaborate T-shirts were popular for much of the early 2010s,” we are told. But by 2014, “Bright colors (especially the Ed Hardy shirts) went out of style in favor of black, white, beige, taupe, gray, and various shades of dark green.” This muting of the palette was thanks to “the improving economy.”

Screenshot via Wikipedia’s “2010s in Fashion” page

This is our own moment mummified, turned into something already distant, something already other.

Though the mostly anonymous authors of “2010s in Fashion” attend to recent and ongoing trends, they maintain a tone of retrospective distance throughout. Consider the “Mid 2010s” subheading. The mid-2010s, a parenthetical suggests, date from 2013–16. This is the present as seen from a possible tomorrow, a dispatch from a future that is already past.

Screenshot via Wikipedia’s “2010s in Fashion” page

Suggesting as it does a summation of present things still to come, the very existence of “2010s in Fashion” may seem puzzling. Seen up close, current fashion is normally kaleidoscopic: It’s not that it resists classification, just that classification entails fragmentation. When we imagine the fashion of decades past, we tend to think in broad strokes—single designs defining entire epochs. Tellingly, many of the Wikipedia pages for the fashion of earlier decades are a good deal shorter than the 2010s one, perhaps because those eras feel more contained than the present does. When we attempt to make more recent trends cohere to this retrospective model, we inevitably estrange ourselves from them.

Screenshot via Wikipedia’s “2010s in Fashion” page

“2010s in Fashion” was first created in January 2011 as a stub; the entry wouldn’t feature any real content until a few months later. Generally civil debates began to break out, with the page’s editors disagreeing about everything from whether preppies would mismatch their socks to the age after which one stops qualifying as a hipster. Above all else, though, they argue about the historical positioning of specific fads and trends. In August 2011, for example, one editor stood up to others about the origins of acid-washed jeans and leggings, refusing to accept that they first arrived in the 1980s. Later, others would discuss how to date the starting point of grunge, pushing back against the received wisdom it kicked off in the early 1990s. And one especially prominent early battle left editors deadlocked over whether Snuggies should be identified with the aughts or the 2010s.

As the Snuggie fiasco suggests, many of these struggles derive from the futile attempt to draw firm distinctions between one decade and the other. They are, in other words, struggles to justify the independent existence of this page itself. To have a home on Wikipedia, “2010s in Fashion” has to make a case that 2010s fashion is a thing—stable and definable, clearly distinct from everything before it.

Screenshot via Wikipedia’s “2010s in Fashion” page

Even when exploring a current trend, the authors often write in the past tense. For example, a note on men’s hair reads, “In the mid 2010s, some men wore their hair in a type of topknot or ‘man bun’ ” (emphasis mine). This rings strange to those of us who are still trying to make sense of man buns today. But on Wikipedia, for the present to become encyclopedic, now must silently transform into then.

At its best, then, “2010s in Fashion” captures the ephemeral quality of fashion itself. It gets at the strange paradox of the present, the way the moment slips away as soon as you try to point at it. It doesn’t capture the fullness or the essence of 2010s fashion, but it doesn’t have to. As one editor noted back in January 2015, “We have 5 more years to enact information overload.” What’s the sense in starting now?