On Sunday night, after a weekend of Joaquin’s wind and rain, I stocked up on fall tights from American Apparel’s online store. I woke up Monday morning to news that the once-hip purveyor of cotton T-shirts and sparkly spandex had filed for bankruptcy. The company was bruised by the megalomania and sexual misconduct of its founder, Dov Charney, but it was finally done in by a simple fact: Nobody is buying its clothes anymore. Nobody except, evidently, me.

American Apparel hasn’t made a profit since 2009, a turning point that has as much to do with shifts in U.S. fashion as with the Great Recession. A bad economy meant that customers traded brand loyalty for better prices—a plain T-shirt costs $28 at American Apparel and less than $6 at H&M. The ’80s and ’90s nostalgia that defined the company through the start of the millennium went stale by the time its target demographic of teens and twentysomethings aged into grown-up clothes.

When it evolved from a T-shirt manufacturer into a complete clothing brand in 2003, American Apparel sold itself on made-in-the-U.S.A., sweatshop-free ethics. Back then, the brand was a status symbol. Its signature $52 hoodie was simple enough to jibe with the effortless, unpretentious aesthetic of the mid-aughts, but distinctive enough, with its white draw-cords and zipper tape, to tell the world that the wearer had $52 to drop on a sweatshirt.

Today’s clothing market plays a different ballgame. Retailers like Zara, H&M, and Forever 21 have quickly scaled up their global footprints in recent years—in H&M’s case, at the rate of one new store opening per day. Rather than marketing a signature style that makes slight shifts with each season, fast-fashion outlets grab trendy new looks from upscale designers, remake them nearly line for line in Bangladesh or Indonesia, and deliver them within weeks to stores across the globe, where they sell for indecently low prices. Unless they’re true 1 percenters, teens don’t care whose name is on the label or whether the garments are destined to disintegrate in the wash. They’re wearing the style of the moment, and by the time the trend is dead, the clothes have fallen apart and are ready to be replaced for cheap.

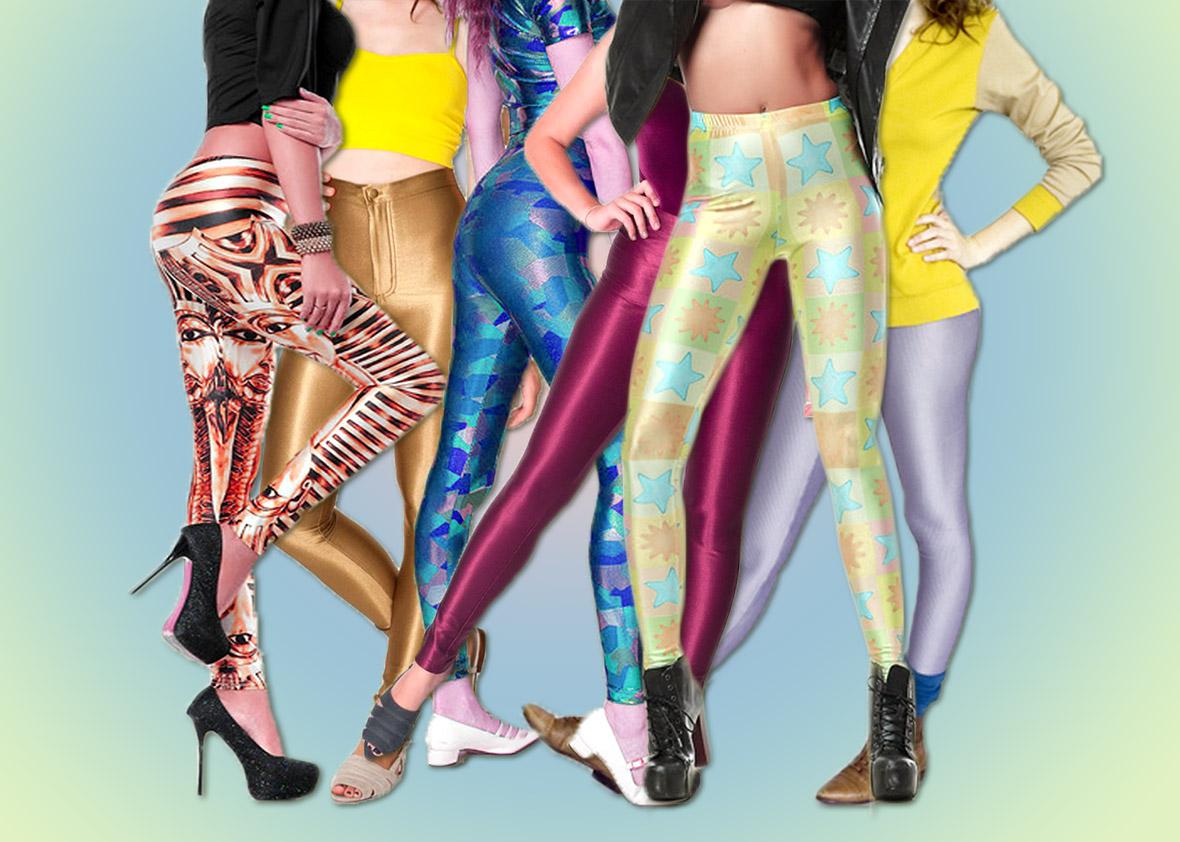

Meanwhile, American Apparel stuck to its solid-color legwarmers and bodysuits, ignoring youth fashion’s swing away from the understated and toward the embellished. Long nails, cheeky makeup and jewelry, psychedelic prints and textures, fringe and fur—other brands had fun with the ways girls make themselves up to look like women, but American Apparel kept manufacturing clothes and ad campaigns that make women look more like girls, in figure-skater halter dresses and pleated skirts.

And the brand wasn’t able to deliver the higher quality that its higher prices would suggest. “They’re not the only company doing the American-made thing,” Elizabeth Cline, author of Overdressed: The Shockingly High Cost of Cheap Fashion, told me. “That whole sector has really exploded in the last five years. It’s not enough to run a brand anymore on ‘Yay, we’re made in the U.S.’ Nowadays, if you produce in the U.S., you’re expected to be producing premium-quality, well-crafted, heritage products.” Cline says consumers who care about both quality and labor standards are willing to pay more for brands like Rag & Bone and Raleigh Denim, which offer domestic-made products that look and feel a step or two up from American Apparel.

I first got to know the brand back in the mid-2000s as the name on the tags of the T-shirts that cool, conscious bands sold at their merch tables. American Apparel was the company whose clothes you wore if you were schooled on global injustice and wanted to do something about it, man. To a clueless adult, most of its neon sportswear would seem barely distinguishable in design from the basic offerings at Walmart or Sears, but to image-conscious teens with an eye for trends and some disposable income, American Apparel’s signature hues and silhouettes were unmistakable. Its stores sold retro fashions I did not, at first, believe anyone would actually buy—I remember seeing racks of high-waisted pants on sale back when it still seemed inconceivable that the style formerly known as “mom jeans” could ever make a comeback. These wan people in track pants must know something I don’t, I thought. The less objectively cool its clothing seemed, the cooler I believed American Apparel could be.

But to stay right with their fad-chasing demographic, brands have to come in one step ahead of mainstream trends every single time, an ever-more-difficult proposition in the fast-fashion race. American Apparel’s bread and butter—selling a few well-made basics in a rainbow of bright colors—was ill-suited for adaptation; when zany prints and elaborate ornamentation came into fashion, the brand didn’t move fast enough. Even in the T-shirt realm, where American Apparel had a home-court advantage, it failed: The luxury T-shirts in leather, cashmere, and ultra-soft jersey that hit it big in 2010 completely bypassed the company’s radar. That year, near the end of my time in college, it seemed like most of the students I knew who still shopped at American Apparel were going for spandex minidresses and sweatbands to fill out their superhero Halloween costumes. Last month, I visited the company’s downtown D.C. store, which sits directly across the street from a two-story H&M. On the American Apparel racks, I recognized a geometric black-and-red print from a pair of harem pants I bought there two or three years ago.

And as other retailers, such as Target, Forever 21, and Charlotte Russe, expanded their markets by launching plus-size lines in recent years, American Apparel doubled down on its commitment to tiny clothing made for tiny bodies: crop tops, shimmery hot pants, and thong leotards, none of which could realistically fit anyone who’d be a size 10 at any other store. I’m usually a size 2 or 4 in standard-size clothing. At American Apparel, I’m a 6 or 8. Until 2009, the company didn’t even make clothes up to its own distorted version of an XL, which it unveiled in an off-putting, tone-deaf rollout that called for “booty-ful” models who “need a little extra wiggle room where it counts.” (Speaking of booty-ful consumers, my editor informs me that even American Apparel’s baby sizes run small.)

Meanwhile, hypersexualized ad campaigns with barely-if-at-all-legal models haven’t exactly fallen out of fashion—and I doubt they ever will—but after years of exposure to POV shots and pubic hair, for much of the public, American Apparel’s once-shocking ads have lost their frisson. Katharine Brandes, creative director of women’s clothing line BB Dakota, has drawn a smart distinction between the urban Vice reader captured by American Apparel in the early aughts and today’s urban Portlandia watcher, who shops local and is grossed out by Charney’s skeevy track record.

Some customers stopped shopping at American Apparel because its styles fell behind the times, or because its connection to a world-class scumbag outweighed its fair labor practices and progressive stances on marriage equality and immigration. Some couldn’t fit into a single one of those sock-size tube tops in the first place. Why do I still buy the brand, besides the fact that it’s responsible for the single best pair of dress pants I’ve ever had the pleasure of wearing? After a few too many poly-blend H&M tank tops turned sheer after a single run through the washing machine, and after a few career moves left me with a more livable salary, I decided to wean myself off of most fast fashion. I still shop at H&M every now and then, but I’m trying to buy more top-quality brands at secondhand stores and get my cheaper basics at places with decent labor standards. If I have a specific idea of what I want—a comfortable cotton T-shirt, a pair of thick tights—I know American Apparel will have it in a shade that will match whatever else I’m planning to wear, and I know a child didn’t go blind making it.

As Cline points out, American Apparel is squeezed in between supercheap, foreign-made brands and higher-end U.S.-made retailers such as Imogene + Willie; American Apparel’s products are more expensive and less responsive to trends than the former, but feature lower-quality material and construction than the latter. If American Apparel stands a chance at resurrection, it should continue scaling back its operations to focus on making better-value garments and retire some of the old prints and styles that no longer register as cool. It should start sizing its clothes within the bounds of reality and try out contemporary silhouettes beyond the bandeau top and the slouchy sweater. It should cool it on the spandex, except for two months out of the year: October, for Halloween, and May, ahead of Pride season. It should give me more shapes and fabrics of T-shirts to buy, because it makes great T-shirts and I already have too many V-necks. Now that Terry Richardson–wannabe Charney is out of the picture, my reservations about the brand are purely design-related. For me and my fellow American Apparel holdouts, the space in between fast fashion and top of the line is the best fit.