Persephone books all look alike. They are the chilled grey color you must spell with an E, like fey, and a tiny maiden poses tastefully in the bottom left corner. The font is elegant, understated, and delicate—feminine but not frothy, like an FKA Twigs song. These are editions that make you want to use adjective-noun pairings like “graceful severity” or “attractive seriousness”—they conjure not the carefree, wildflower-gathering Persephone that Hades swept down to the Underworld but rather a queen in a cool room, wearing a clean and becoming shift. She is discriminating and has exquisite taste, her fingers trailing in the Styx. She has a cult following back on earth.

Persephone, the publisher and bookseller, has a cult following too. The company reprints books mostly from the early-to-mid-20th century, and mostly by women. It seeks out blockbusters from the interwar period that have disappeared from view—once-ubiquitous offerings from the likes of authors Dorothy Whipple or Susan Glaspell. Its 112 titles include novels, diaries, letters, memoirs, and poems; they come to Persephone’s attention via reader recommendations, secondhand bookstores, and musty advertisements in the endpapers of contemporaneous texts. The company’s founder, Nicola Beauman, studied domestic fiction from the 1920s and ’30s at the University of Cambridge, which explains the niche-y focus. As for the grey, “well, we really like grey,” says Beauman’s daughter Francesca, who runs the Bloomsbury, London–based house’s U.S. operations.

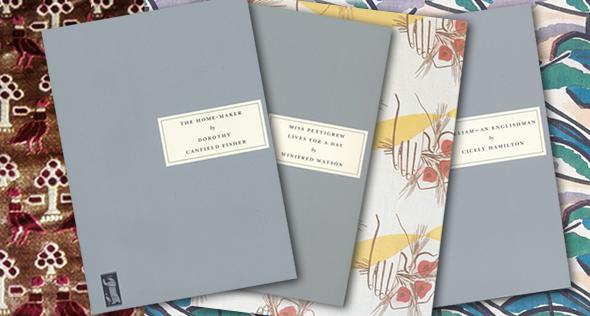

Persephone, which began in a tiny room above a pub in 1998, chose Cicely Hamilton’s William—An Englishman as its first title. The novel, telescoping between miniaturism and sweep, charts the reverberations of World War I through the lives of a young couple. Three years later, the 21st selection, Miss Pettigrew Lives for a Day, by Winifred Watson, became a surprise hit, adapted in 2008 into a movie starring Amy Adams and Frances McDormand. That windfall gave Persephone both the means and the buzz to expand, though its architects try to sustain Beauman’s original, specific vision: “Memorable plots with strong themes and gripping characters … centered on the home and the overlooked details in life,” as Francesca puts it.

Those criteria are what led the elder Beauman to, for instance, To Bed With Grand Music, a 1946 novel by Marghanita Laski, about a World War II–era wife who would rather conduct an escalating spiral of love affairs in her husband’s absence than keep the home fires burning. “Although it chronicles immorality,” historian Juliet Gardiner writes in the introduction, the book “is not in itself immoral. … This is an ahead-of-the-pack telling of an aspect of the civilian’s war it was not yet acceptable to reveal.” Or consider 1924’s The Home-Maker, by Dorothy Canfield Fisher, which presciently unfolds the story of a family in a small New England town after the father’s accident forces him to switch roles with his stay-at-home wife. Both narratives upend perceptions about what life was like in their respective eras to show the diversity of experiences contained by the domestic sphere.

To pick up a Persephone book is to encounter a minutely specialized, painstakingly crafted brand, one that I took a stab at characterizing as feminine before Beauman corrected me: “Not so much feminine as domestic,” she said. “We are interested in men and women in the privacy of their homes.” The deceptively modest scope of the books—about 20 percent of which are written by men—helps them re-create the texture of their lost eras with a pointillist clarity. Characters go off to war, or experience poverty, or enter political life, but each fine-grained detail (“the police are breaking down the door, and she’s fretting over who will hang the laundry if she’s in prison,” Beauman says of the heroine of No. 50, The World That Was Ours) helps complete the imagined world. According to Persephone’s founders, this is something contemporary literature has forgotten how to do.

The failings of the current book scene come up again and again in my conversation with Beauman. It’s obsessed with grand themes. It’s relentlessly male. It trivializes experience on the molecular level and demands we kneel before its ambition. (Karl Ove Knausgaard, whose novels are at once megalomaniacal and intensely interested in the accretion of mundane ephemera over a life, counts as both the exception and the rule.) So much of Persephone’s meticulous attention to detail—from the beautiful fabrics that make up the endpapers, each designed the same year as the book’s first publication, to the loving descriptions of plot and context on the company’s website—seems like a response to the insane abundance of Literature Today. There’s too much of it. It’s too big. If we don’t pay attention, we’ll miss all the radiant particulars.

Fascinatingly enough, the same (or same-ish) anxieties were at play during Persephone’s favored decades between the wars. The 1920s saw a flourishing of commercial novels, especially by women, and especially in the genres of romance, historical fiction, westerns, and crime. It was the heyday of Zane Grey, Sinclair Lewis, Edna Ferber, and Dorothy Canfield, Anita Loos, Kathleen Norris, and E.M. Hull. The phrase “mass media” was coming into vogue. And in response to all the profusion, readers sought out cultural curators: subscription book clubs, such as Harry Scherman’s Book of the Month Club or Samuel Craig’s Literary Guild, that recruited “experts” to assign titles to members, and best-seller lists, such as the New York Times’, which appeared in 1931.

Persephone has an “A Book a Month” program too. “We’ve all walked into Barnes and Noble and felt paralyzed by so much choice,” Beauman says. “For someone you trust to thrust a book into your hand, saying, ‘Here you are, take this, you’ll love it’—isn’t that the dream?” Persephone goes above and beyond to cultivate readers’ trust, which is another way of saying it must constantly protect and refresh its image. The house—whose titles sell anywhere from 50 to 50,000 copies, depending on the book—has turned down several “very famous” celebrity endorsements in deference to “British understatement … in all its chic, elegant glory,” Beauman says.

My first Persephone title arrived in a gorgeously wrapped parcel—yellowy white, with a floral bookmark tucked under a silver ribbon—no bigger than an Etch a Sketch. It was No. 112, Vain Shadow, by Jane Hervey, a dark comedy about the funeral of a tyrannical father. In it, siblings vie for their desiccated inheritance and a soufflé is “as light as a fart.” Hervey’s voice is extremely distinctive: pungent, close, calm, and precise. I would not want to listen to it exclusively. But tearing through one chapter, and then the next two, I did not want it to stop, either.