Rolling Stone issued a statement today saying it can no longer stand by its story about a brutal gang rape of a young woman named Jackie at a University of Virginia fraternity party. “In the face of new information, there now appear to be discrepancies in Jackie’s account, and we have come to the conclusion that our trust in her was misplaced.” The magazine did not elaborate on the new information but the Washington Post, which has essentially been re-reporting the story since it broke last month, and representatives for the Virginia chapter of the fraternity, Phi Kappa Psi, started providing the details.

According to Phi Kappa Psi lawyer Ben Warthen, the frat apparently did not host a party on the night of Sept. 28, 2012, which is when Jackie said she was lured upstairs by her date, “Drew,” and gang raped by seven men. Jackie had said she met Drew because they were lifeguards together, but no member of the fraternity was employed by the university’s Aquatic Fitness Center during that time frame. Also, the Rolling Stone story implied that the rape was some kind of an initiation ritual, but pledging takes place during the spring semester, not the fall.

Up until now, Jackie had been reluctant to reveal the name of the man who took her on the date. But this week, according to the Post, she told it to some of her friends—activists who had supported her since the alleged rape. The man whose name she gave belonged to a different fraternity, not Phi Kappa Psi. A Post reporter contacted him and he said he knew Jackie’s name but had never met her in person or taken her on a date. That’s a detail to pay attention to. He could be lying, of course, but that’s a pretty bold lie, not just to say he’d never dated her or taken her to a party but he’d never met her.

The rest of the Post story so far paints a confusing picture and leaves the impression that the Post reporters are not quite ready yet to call Jackie’s story a fabrication. Jackie recounted to Post reporter T. Rees Shapiro the same story she had told Rolling Stone and added some details, saying, for example, that her date had taken her to an extravagant dinner at Boar’s Head Inn. She called the night of the rape “the worst three hours of my life” and said “I have nightmares about it every night.” Her roommate from that year Rachel Soltis confirmed that Jackie changed during that semester and became “withdrawn” and “depressed,” although she wasn’t with her the night Jackie says she was assaulted.

So where does that leave us? It’s still quite possible that something happened to Jackie that night. It’s possible she was so traumatized that she is getting a lot of the details wrong, or that whatever happened to her has taken on greater levels of baroque horror in her imagination. It was hard to take in her original story, of a calmly orchestrated gang rape during a big party. But it’s just as hard to take in that a young woman would make up such a story, tell it to a reporter, and not expect it all to unravel. But strange things happen. And more information will surely come out soon.

One thing we know is that Rolling Stone did a shoddy job reporting, editing, and fact-checking the story and an even shoddier job apologizing. In his statement, managing editor Will Dana says the magazine relied on Jackie’s credibility and now realizes its trust was “misplaced.” (In a later series of tweets on Friday, Dana wrote that the failure “is on us—not on her.”) But any story, much less one as damning and explosive as this one, should never rely on just the credibility of one source. Earlier this week, the editor of the story, Sean Woods, told the Washington Post about the men Jackie was accusing, “I’m satisfied that these guys exist and are real. We knew who they were.” But the Washington Post reported today that Jackie never told anyone who they were until this week. Jackie may turn out to have partially or totally fabricated her story, but the blame is on Rolling Stone for putting her in this position, and for the damage done to the members of Phi Kappa Psi whose names have been circulating around the Internet for the last few days. People lie. It’s better when they don’t. But it’s Rolling Stone who blew this woman’s story up into a huge national issue without doing any of the work to make sure it was true. (Which is why we are not using Jackie’s full name.)

The dance between reporter and source in this case seems to have been a dicey one. The reporter, Sabrina Rubin Erdely, told us on the DoubleX Gabfest that she had been looking at different campuses to find an example that would illustrate how badly universities handle allegations of campus sexual assault. She came upon Jackie’s story of a gang rape, and, as any reporter would, concluded this was a story that needed to be told. If universities couldn’t even properly handle a brutal, orchestrated gang rape, then the system was seriously broken.

Jackie told the Post that she felt “manipulated” by Erdely. She said that she was “overwhelmed” by sitting through interviews with her and asked to be taken out of the story, but Erdely said it would go forward anyway. Jackie said she “felt completely out of control of my own story.” Erdely has implied that she made an agreement with Jackie that she would tell her story but not try to contact her assailants. Rolling Stone explained in their statement today: “Because of the sensitive nature of Jackie’s story, we decided to honor her request not to contact the man she claimed orchestrated the attack on her nor any of the men she claimed participated in the attack for fear of retaliation against her.”

Such agreements are apparently not uncommon. In survivors’ groups, advocates advise victims to strike these kinds of deals with reporters so they don’t lose control of their own stories, or anger their assailants, both of which they consider paramount to healing. But this creates an impossible situation for journalists: Ask too many questions and you lose your source. But don’t ask enough and you end up in this situation, with a story that’s falling apart. (Third and very legitimate option: Kill the story.) Late Friday, Dana also tweeted that Rolling Stone should have “either not made this agreement with Jackie,” or “worked harder to convince her that the truth would have been better served by getting the other side of the story.” It must be said, though, that there are many ways of verifying a story without directly contacting the assailants. Visiting the Aquatic Center to see if a member of Phi Psi worked there, for one. Finding out from other people if there was a party that night. Talking to the friends who Jackie said picked her up after the alleged incident, which we are still not sure the reporter did. (Update, Dec. 7, 2014: Two of the friends have now talked to the Washington Post, and say that they never spoke to Rolling Stone.)

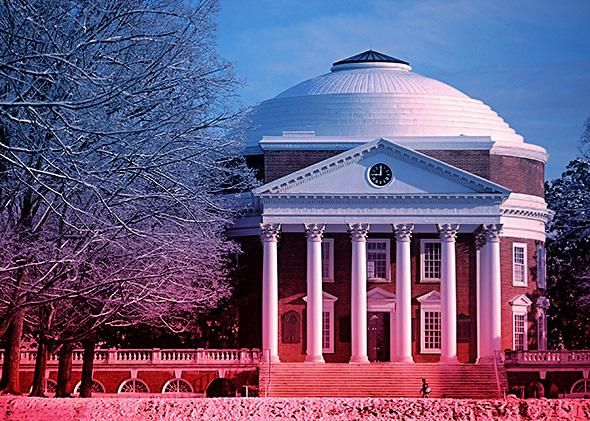

Fake rape allegations may be very rare but they have a huge impact, especially when they get so much attention. Recently I heard a story from someone who went to the high school with one of the Duke lacrosse players who were accused of rape. It was an all-boys school and when they heard they had produced a rapist they went through some serious soul-searching, reconsidering some of their traditions and educating the boys on sexual violence. When they learned the rape charges were trumped up, the school rallied around the boy and forgot about the reforms. Will the same thing happen at UVA, which seemed to be on the cusp on making changes at the school to better protect women from sexual assault? UVA president Teresa Sullivan says no. “Today’s news must not alter this focus,” she wrote in a university-wide email today. “Here at U.Va., the safety of our students must continue to be our top priority, for all students, and especially for survivors of sexual assault.” I hope that’s true.

One thing I heard several times when trying to do re-reporting myself: Many people had doubts about the details in the story, but didn’t really care, as long as it was effecting change at UVA. I don’t agree. But I still hope we can salvage some good from this episode, even if Jackie’s story proves false. Perhaps one thing we should look at is how we treat victims of sexual violence so differently than other victims, and whether that serves them. When I initially reached out to the advocates who had supported Jackie, they wondered if maybe the media was doubting the story because it was about rape, and people have always doubted victims of rape, and held stories about rape to a higher standard. But what this Rolling Stone story shows is that maybe we’ve reached a point where we hold stories about rape to a lower standard. What we should hope for instead is a world where college administrators, and reporters, can ask a victim of sexual assault questions and carefully investigate without it being seen as a betrayal of the victim but rather as part of the effort to seek justice.

Finally, if this turns out to be a fabrication, we should wonder why we were so quick to believe it. In the last few days, the names of the fraternity members started to leak out, and many of us began to look up their Facebook pages. I found myself playing the profiling game: Is that the kind of haircut a rapist would have? Are those the kinds of girls he would have hanging all over him? Oh, yeah, that bro is totally a rapist. If the boys remain shadows in these stories, as so many of them have as we’ve (rightfully) focused our attention on campus sexual assault, then we can project all our prejudices onto them. Which is exactly what people did to women for all those years.