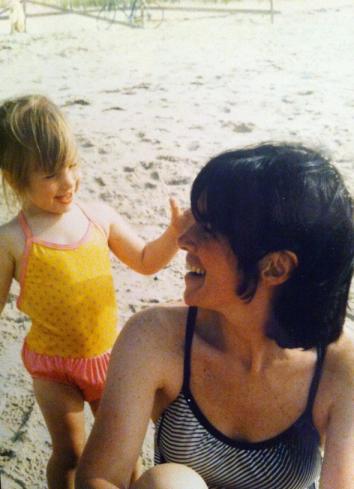

This is me as a kid: I sleep in a ball, hugging my knees to my chest. I pull the covers over my head and face the wall. This way, if a murderer comes in to kill me, I won’t have to face him. He can get the thing over with before I know it’s coming. By day, I am restless legs and nervous habits: picking the skin on my lips, peeling back my nails. In third grade, my teacher calls my parents to say that I’ve been squinting in class and might need glasses. But my vision is perfectly clear. The squinting is a facial tic, an outward manifestation of my inner disquiet.

My muscles are wound so tightly that my violin teacher gives me extra exercises to loosen up: “You’ll never learn vibrato if you’re squeezing so hard.” But I excel at track and field, my body like a dormant coil waiting to spring awake in the 100-meter dash. I am safe and fed and happy, but I am worried all the time.

Looking back, it’s tempting to say that all this worrying was prophetic, spurred by a vague premonition of some future tragedy. That’s how the story goes if I tell it from back to front. There would be a series of events to validate my worrisome nature, but before those things happened, I was just born that way.

When my mom got cancer for the first time, I was 12. Until then my worry had been refracted in a hundred splintered rays, diluted by its lack of focus. Now it was a concentrated beam of light, shining intently on those mutated cells. Science tests and playground squabbles had been a dress rehearsal for the main event. My worries now were grander and graver, punctuated by the sound of retching in the bathroom, the urgent trips to the clinic for hydration.

My mother’s death was, at that time, not imminent. Stage 1. Clean margins. Good prognosis. Cancer is a spectrum, muted fear and discomfort on one end and absolute doom on the other. There’s a lot of nuance in between. But try explaining nuance to a 12-year-old who believes that an intruder might kill her in her sleep. Worry was my default, and life continued to confirm that it was warranted.

When I was 16, with my mom approaching the five-year anniversary of her remission, my dad got “the worst headache of his life.” These are the words he used to describe it. These are the words a lot of people use to describe a ruptured brain aneurysm.

It was the fall of my junior year of high school. I was studying for the SATs, stressing about where to apply for college and struggling to get the concepts of precalculus to stick in my math-averse brain. I spent a dozen hours a week on the soccer field and tried to figure out what it meant to be someone’s girlfriend. I was already on edge when my dad went in for a 10-hour neurosurgery with 50-50 odds of survival.

While my mom’s cancer and the treatments that followed had stretched over months, my dad’s aneurysm was touch-and-go from the start. Forty percent of people with a ruptured aneurysm die on the spot. Two-thirds of survivors have lifelong cognitive impairment. There had been a ticking time bomb inside of him that not even he had known about. It blew up, and all we could do was wait to see how the debris would fall.

What this meant, in practical terms, was that every day was a day my dad might live or die. Beyond the initial rupture and the risky surgery, complications arose at least weekly: meningitis, vasospasms, cerebrospinal fluid leaking out of his nose. I spent my days at school anxious and exhausted, wearing headphones to block out the noise. I went to soccer practice, went to the hospital, did my homework, passed out.

Six weeks went by. Leaves turned yellow and then red and then brown without my noticing. By what some would call a miracle and I would call a combination of luck, my mother’s fierce advocacy, and a few of the best doctors in the world, my dad was released from the hospital in time for Thanksgiving. Though his muscles were atrophied and his voice worn away by tubes, he was not a vegetable. He was still my dad.

And I was still my worried self, only that worry was shape-shifting, swimming around inside me looking for places to lodge. The bright red thread of illness began to stand out against my otherwise unremarkable life. My anxiety lifted like a cloud of smoke from quotidian high school matters and settled on the fatalistic. Life-threatening illness had struck both my parents. When would it strike me? What was this bump on my arm or this tightness in my chest? Surely signs of my own premature death. And when would I lose a parent? That question felt as immediate as wondering what we’d eat for dinner that night.

When, as it happened, would be eight years later, when I was 24 and living in New York. Or at least that’s when it would begin. My mom gathered my siblings and me to tell us about her new diagnosis—not a relapse of her breast cancer, but a new type of cancer altogether. Another simple case of bad luck. We conjured a collective sense of optimism: She’d been through it before, she’d get through it again. But we were wrong. She was gone in 2½ years’ time.

I had spent my whole life worrying, until the thing I was worried about came true. My worry didn’t whoosh out of me like a billow of steam from a locomotive, one quick burst of exhaust and the train keeps pressing on. It happened in two phases: First the small stuff, then the big. The small stuff began to lose its urgency when my dad was still in the hospital. A classmate walked up to me between classes, her planner open to that night’s assignments. As she recited the chapters and problem sets that would keep her up past midnight in a futile attempt to elicit my sympathy, I watched her lips move, and the voice inside my head drowned hers out. You just don’t get it, I thought, aware, rather suddenly, that I did.

The second release, when I stopped worrying about the big stuff, happened near the end of my mom’s life. My mother wouldn’t be at my someday wedding or know my someday children, leave me another voice mail or send another over-the-top Valentine’s Day package. But as the recognition of these losses weighed me down, the burden of worry dispersed. There was nothing more to fear.

In reality, the graph of my declining worry probably looks less like two solitary plot points and more like a scattered electrocardiogram: There were spikes, and there was a slow seeping, peaks and valleys and sinusoidal curves between the points. It was more complex than I can describe, or maybe more complex than I can know.

When I look back on that little girl sleeping in a ball, all I can think is that she was right. Something terrible was coming. But what is there to worry about after the worst thing happens? As it turns out, not much. I still have my concerns: about my career, the people I love, the sordid state of global affairs that haunts my Twitter feed. But I no longer expect every plane I board to crash or anticipate bad news every time my phone vibrates. I don’t look up every unusual ache on WedMD and skim straight to the fatal outcomes. I’ve internalized a sense of productive helplessness—if there’s nothing I can do to keep tragedy from barging into my life, the least I can do is not let the very idea of it take over.

I recently read John Green’s teen cancer drama The Fault in Our Stars, because I’m a masochist and I need to cry sometimes. In it, one teen lover says to the other, “Grief does not change you, Hazel. It reveals you.” Grief changed me, though. If you peeled back all of my layers 10 or 20 years ago, they would have revealed a core of twisted twine, knots and tension, no room to breathe. My grief unraveled that core. My anxiety moved on and left a gaping hole, an emptiness where once there was a mother to worry about.