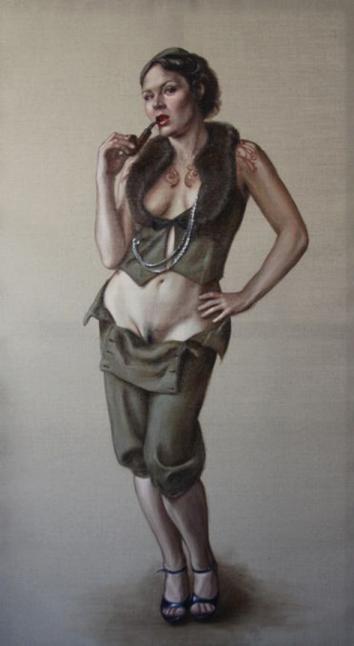

Earlier this month in London, artist Leena McCall’s Portrait of Ms Ruby May, Standing was removed from the Society of Women Artists’ annual exhibition at the Mall Galleries. London- and Berlin-based artist McCall says she was told the painting was taken down because it was “pornographic” and “disgusting.”

What is so disgusting about it? The painting depicts a healthy woman standing with hip cocked, gaze trained on the viewer, one eyebrow raised in a suggestive, come-hither look. She is sporting the kind of cleavage that would make Salma Hayek proud. Sure, she is tattooed and smoking a pipe, but what really sets the image apart is the area below her olive-green, unbuttoned trousers, which have fallen just far enough to reveal the black landing strip of her lady-garden. This, apparently, was the part deemed “pornographic.”

Painting by Leena McCall (http://leenamccall.com/)

The Mall Galleries says the painting was yanked to protect “children and vulnerable adults” who visit the gallery. (Vulnerable to what has never been made clear.) The painting has since been replaced by another female nude, this one less challenging—and presumably less hairy.

When did pubic hair get so threatening? It’s tempting to think that the disappearance of the bush is just another arrow in the quiver of modern patriarchy. I, for one, have always assumed that my foremothers were well-protected by a soft pillow in the places where the sun don’t shine, and that it was only some Don Draper character who introduced the razor into my bubby’s beauty routine. The reality is more complex: There are ancient recipes for hair removal using everything from arsenic to “a distillation of swallows,” and the practice of removing body hair goes in and out of fashion for women throughout history. (The current trend, according to the New York Times at least, is “the fuller look.”)

But the pattern in art history is remarkably consistent. Until the 20th century, depictions of women in Western art usually avoided showing pubic hair, particularly in images meant to represent ideals of art and beauty (as opposed to, say, filthy prostitutes). Classical Greek sculpture included pubic hair on men, tight little curls of adornment, but the female mons was almost always fuzz-free. This classical ideal dominated painting through the Middle Ages and Renaissance (think of Botticelli’s Venus, and the smooth white triangle that disappears into the long golden hair falling from her head). Titian, Rubens, Michelangelo—they all avoided showing ladyfur. Francisco de Goya’s La Maja Desnuda, painted around 1800, is sometimes said to be the first painting to show an ordinary naked woman with pubic hair, and it was deemed so provocative the Spanish prime minister kept it in a private room. The painting was one of the reasons Goya was later called before the Inquisition.

Even during the development of photography in the 19th century, “artistic” nudes had their pubic hair blotted away with an airbrush. One oft-repeated (though controversial) story has it that the great English art critic John Ruskin spent so much time with hairless art nudes that, when he discovered his wife’s body hair on their wedding night, he couldn’t consummate their marriage. (She ended up leaving him for his protégé John Millais, apparently a bush man.)

In movies, too, female pubic hair is considered irredeemably, and problematically, erotic. The documentary This Film Is Not Yet Rated revealed that the 2003 Vegas flick The Cooler was given an NC-17 rating thanks to 1.5 seconds of Maria Bello’s pubic hair. The whys and ways of the MPAA rating board are somewhat mysterious, but after directors agreed to cut the pubic hair (though not the oral sex leading up to it), the film earned the far more commercially viable R rating. Meanwhile, films that show horrific violence against women—like The Killer Inside Me, which lingers over the graphic murder of its female leads, or The Girl With the Dragon Tattoo, which features a long anal rape scene, are given an R rating. (A new documentary called The Secret Garden is entirely devoted to the question of what women do with their pubes. It hasn’t been released in America yet, so no word on what rating it will be given.)

What’s going on here? Why are we so terrified of a little bit of pubic hair? My guess—and it’s not earthshattering—is that it has everything to do with our fear of adult female sexuality. From an evolutionary standpoint, the appearance of pubic hair in women coincides with the onset of ovulation; seeing it tells men a woman is old enough to breed, so it’s an important trigger for sexual arousal. Breasts, of course, are another sign of sexual maturity, but they also have maternal connotations, and they aren’t kept as hidden as pubic hair. (Secret things are always the most erotic.) Sure, some people think it’s sexier to remove body hair—the interplay of nature and culture is one of the many wonderfully complex things about being human—but there’s an undeniable intertwining of adult women, sex, and the hair down there.

In fact, some art historians posit that the reason classical images of the ideal nude figure are so frequently hairless is because of the association between hairlessness and childhood, and thus, virginity. Once again, the ideal woman is a frigid Virgin: not exactly sex-positive.

And there’s another angle at play, one that takes our fear of adult women as agents of their own sexuality even further. As Rowan Pelling pointed out in the Guardian, the Ruby May painting includes a gaze trained at the viewer (Goya’s did too), and this combined with the pubic hair might be most threatening of all. “It seems the Mall Galleries’ clientele can cope with nudes, so long as the model is a more passive and unthreatening recipient of the wandering viewer’s gaze,” Pelling wrote. “The implication’s clear: the minute a woman is alive and free to move, an active agent of her own sexuality, she is a menace to society.”

The removal of the painting is particularly ironic—or perhaps just telling—given that McCall’s mission with it was to address “how women choose to express their sexual identity beyond the male gaze.” The real Ruby May, who leads erotic workshops in Berlin, told the Independent: “I don’t think people realize how threatening a sexually empowered woman is to a paradigm that is still patriarchal at its roots. Thankfully, the world is evolving, this outdated paradigm is crumbling, and forms of censorship such as this are becoming unacceptable to the wider public.” McCall says that it was May’s deliberate choice to display the pubic hair that is so often waxed, trimmed, Naired, or Photoshopped out of existence.

Since the painting’s removal, McCall launched a Twitter campaign asking supporters of the work to tweet at @mallgalleries using the hashtag #eroticcensorship. Partly as a result of the outcry, the painting will be re-hung at the Leyden Gallery in London, where it will be on display until July 26. Let’s hope no children or “vulnerable adults” visit. And next time you’re watching an onscreen sex scene without any pubic hair, it’s worth asking what, exactly, we’re so afraid of.