President Obama was asked recently about regrets. “I regret not having spent more time with my mother,” he said. The president’s mother, Ann Dunham, died at age 52 when Barack Obama was 34. “I was so busy with my own life that I didn’t always reach out and communicate with her, and ask her how she was doing and tell her about things. You know, I was nice and I’d call and, you know, and write once in a while … I realize that I didn’t, uh, every single day, or at least more often, just spend time with her and find out what she was thinking and what she was doing because she had been such an important part of my life.”

I know how he feels. My mother died when I was 29, and though it has been 17 years, I still have the instinct to call her. She was also a journalist, so there’s the news to talk about, and there are the anniversaries of big events that she covered, and now that I have kids, there’s the larger set of conversations we could have about ambition, faith, fear, and generally trying to keep it all together. But the president is not describing conversations he might have now, he’s regretting conversations he didn’t have then—all that he could have learned from this trusted source and all that he could have given her. Now that we are parents, we know how powerful a child’s love is when it comes back in simple conversation. This is the real sting. You had all these little presents and you didn’t give them.

The president told the young people in his audience to call their parents. And, yes, by all means call your mother (and call your father too, for that matter). But there’s also homework in this regret for parents: Write to your children now for when they’re older. Leave them some writing for after you’re gone.

I called my mother almost every day for the several years before she died, just as the president suggests. We’d had a bad relationship when I was a teenager, but we repaired it. I was a secretary trying to break into the news business, just as she had once been. I faxed her the stories I was trying to write. She told me about the way Washington used to work. But even in that perfect circumstance, the ability to “find out what she was thinking and what she was doing” was impossible. Child-parent conversations are out of phase. I didn’t know what questions to ask to really get at the truth of her life. I was busy trying to figure out who I was, which was all the shelving in my brain could accommodate at that age. My progress was fun for her to watch. It reminded her of her own. She didn’t want me asking deep, plumbing questions of her.

The greatest lesson my mother taught me was about resilience. She could take a punch. For almost a decade they told her she couldn’t go on television because she was a woman. She never gave up and in 1960 became the first female correspondent for CBS News. She was attractive, which made life easier for her in lots of ways but made it hell too. A lot of the men she needed to take her seriously were either chasing her around the desk or minting bawdy knee-slappers for the boys. She plowed through it. Not long after I was born, she was fired from NBC. She went out on her own and made documentaries.

I know about her grit not because I witnessed it (I was too young) and not because I asked about it (I was too self-obsessed) but because I discovered it in the personal papers she left me after she died.

After Mom was let go by NBC, my parents had no consistent income. In 1970, when I was 2, Mom made a new will and wrote her five children a letter explaining why she’d written it the way she had. “Today I made out my will. If I die anytime soon, you all may wonder why I did what I did. Times have been very difficult for the past year. I am making a lot of speeches and flying all over to earn some money. Each time I get in a plane, and as you may suspect, I am a terrible coward about flying, I worry about what will happen to all of you if there is a crash.”

The letter is typed on blue carbon paper. She had long nails, so when she hit the keys it made a wonderful racket I could hear down the hall in my room. For the next few paragraphs she explained the decisions she’d made and then tried to deliver one last final piece of advice. “I leave each of you all my love and the fervent hope that you will always try to do your very best—better than anyone might rightfully expect—and the hope that you will never stop trying. I also leave my sincerest thanks for being so dear and so nice to me.”

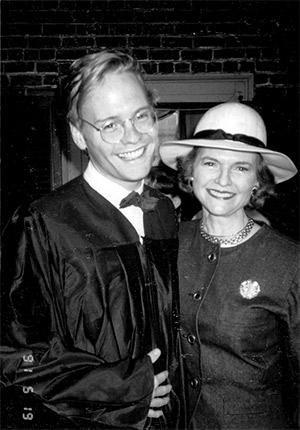

Photo courtesy of the author

I was too young to understand any of this at the time, but even if Mom had said these things in conversation before her stroke in 1996, I probably would have ignored the first part about trying—it would have seemed trite—and the second would have seemed maybe just a little sappy. When I read it now, I know the context. Those words about trying have weight because I know about her life. I know how hard she had to try and I can see that one little moment—alone and scared in a dark jumpy plane, doubting yourself. I also know what that letter meant for her, because we are in phase now. I am about the age she was when she wrote that letter. I have little people upstairs reading past their bedtime whose future now depends on me.

There are also the things Mom left that were not written directly to me. I have her childhood journals, her letters to her parents when she was just starting out, and her journals as an adult. There was so much in what she left after her death, I had to write a book to figure out what it all meant. In those artifacts I’ve learned about grace during times of struggle and self-doubt. I’ve seen examples of a joyful spirit alive in each day. This window into her inner life offers a more global lesson: People are always more complicated than they seem. Your guesses about what motivates them are often wrong. This is both true about her and true about the people she judged. Not all the lessons I’ve learned from these papers are behaviors I’d emulate.

Mom also kept letters she wrote to me, which prove my point. I don’t remember getting them when they were originally sent (“I get the feeling you don’t read my letters,” she wrote to me, saying it was a line her mother wrote to her), but they’re full of wisdom as I reread them. And instruction: “always keep smiling and making people happy,” she wrote on my copy of her letter about her will. This kind of thing reminds you of yourself later in life when maybe you need to be put back on course. Someday my son will need to be reminded that he put a jar of mayonnaise in the sink while we were making dinner and said, “Cinco de mayo.”

A letter I just rediscovered after writing that previous sentence suggests that if I want to become a writer I should “keep a journal daily. … It’s amazing how your perceptions change as you go along and are often vastly different from what you remember them to be at the time first experienced.” (Thanks for the transition sentence, Mom.) This is why it’s necessary to write to your children now. Your perceptions change as you age. A 30-year-old parent writing to a future 30-year-old child sounds different than a 60-year-old parent writing about what life at 30 was like.

But how do you pull this off, exactly? At what age will they start getting these letters? Or do you save them till you’re gone? My kids will have my notebooks and Facebook posts and tweets, but that doesn’t add up to much. I’m not sure I’m ready to hand over my journals to my kids. The letter is the most intimate, accommodating voice, but do you write it straight up or do you frame it around a question? There are some models in Posterity: Letters of Great Americans to Their Children, but “Dear Kids, Here Are Universal Truths” seems a little formal. Plus, that’s my dinner table routine. Mary Lou Quinlan discovered a box of notes her mother had written to God petitioning on behalf of family, friends, and strangers. She wrote about them in The God Box. Those notes convey the truth of things—the light and spirit of a person—but without the explicit form of a letter.

With Mother’s Day coming up, I’d love to find an airmail envelope with my mom’s writing on it that reads, “To be opened on Mother’s Day 2014.” But I’m just being greedy. I have a lot already. Instead I’ll start writing the one to be opened on Father’s Day 2034.