When a story breaks that involves sex without consent, like Dylan Farrow’s or Daisy Coleman’s, or the accounts of unnamed victims at Penn State or in Steubenville, Ohio, how do we decide when to use the terms sexual abuse, or sexual assault, versus the words molestation or rape? Outside of the court of law, have all these terms become interchangeable? Or should we try to use each of them in distinct ways?

Almost 40 years ago, feminist writer and activist Susan Brownmiller began trying to change the meaning of rape by scrubbing the word of shame for victims. In her 1975 book Against Our Will, Brownmiller argued—and bless her for it—that “rape is a crime not of lust, but of violence and power.” This fundamental insight gave feminists one of their most important causes. It also helped fuel a drive to redefine rape not just in our minds but in state laws. Reformers wanted to broaden the crime to include male victims, they wanted to increase reporting (still an issue), and they wanted to get rid of the requirement that a victim show that he or she had resisted.

In some states, reformers pushed legislators to replace the word rape with sexual assault. The idea was to “shift the focus of the crime from the sexual to the violent aspect of the crime,” according to this article by Stacy Futter Jr. and Walter Mebane in the Berkeley Journal of Gender, Law, and Justice. “Equating rape with other assaults was designed to divert attention away from questions of the victim’s consent,” write Ronald Berger, Patricia Searles, and Lawrence Neuman in the Law and Society Review.

And yet, the word rape is still used in 24 states, DePaul University law professor Deborah Tuerkheimer found when she recently asked her students to canvass state laws. Sexual assault is the next most common wording used, with 14 states, her students found. (Other terms the students noted: criminal sexual conduct, sexual battery, sexual intercourse without consent, criminal sexual penetration, and sexual imposition.)

I’m glad that the most common codified term for sex crimes that involve penetration is still rape because it is also still the best term we have for signifying the innate brutality of unwanted sex. With its harsh vowel sound and single syllable, and because rape isn’t primarily a legal term, the word is in no way a euphemism. It’s unflinching. It dates to late 14th-century France, where it meant “seize prey, abduct, take by force,” and before that, it probably came from the Latin rapere, which has the same set of meanings as the French and was also occasionally used by the Romans to mean “sexually violate.”

Of course, not all acts of rape involve seizing by force. In fact, it’s been crucial to remove the element of force from statutory definitions, as the Department of Justice did in 2012, finally bringing a 1927 federal law into modern times and following on the heels of most states. But the powerlessness the old archaic word conveys is crucial to understanding why it is devastating for victims. What Susan Brownmiller did for the word rape—make clear that it’s about violence, not sex—is exactly why I want to keep it. She drew the lines.

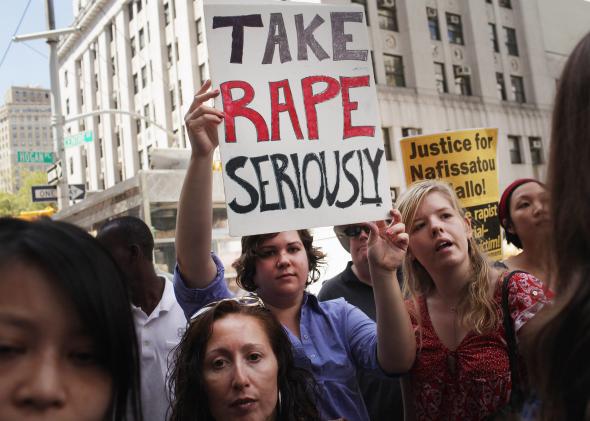

Rape culture is also a useful feminist phrase. It’s the handle for identifying—and dismantling—the misogyny, stupidity, and binge drinking that enables two high-school football players from Steubenville to rape a 16-year-old girl, that allows for humiliating pictures and gossip about the rape to circulate on social media, and that permits some people to rally behind the rapists rather than the victim. Though there are questions about how the story played out online and in the media, where the town and its athletes were widely condemned, there was also vile slut shaming and a disturbing video in which another football player (not one of the two convicted) talked on and on about the assault, saying, “She is so raped right now,” as an audience of boys laughed crazily. Rape culture isn’t a legal term that sends anyone to prison. But it is ugly and real and all too prevalent, as these examples from Soraya Chemaly make clear. I’m glad we’ve found the language to talk about it.

What about sex crimes that involve touching or grabbing but not penetration? As a more general term, sexual assault can cover this terrain in a way that rape, technically, does not. But as David Finkelhor, director of the Crimes Against Children Research Center at the University of New Hampshire, pointed out over email, “Sexual assault implies physical force, which is not present in most sex offenses involving adult offenders with children.” Sexual abuse is useful here. The term has a limited meaning for child protective services, Finkelhor told me: In that context, it’s only used for cases involving caregivers. But that’s a convention most of us don’t follow, and I don’t see why we should. In this case, the older word, molestation, is a little vague, and it’s also primarily thought of as applying to adults with young children. Finkelhor says he favors two approaches when talking generally about nonpenetrative sex crimes against children. “One is just to refer to sexual offenses against children (or minors or juveniles). Another option is to say sexual abuse/assault.” He says that clearly includes peer offenses and date rape.

I see that, but I also think it doesn’t force us to face the horror that children, and adult victims too, experience. The best way I can explain what I mean is to quote the novelist and screenwriter Rafael Yglesias, whose words are hard to read, which is why I’m asking you to:

Sexual assault, statutory rape, sexual abuse, and sexual molestation are clinical and legal terms that irritate me as a writer because they are vague and mislead the hearer. I used to say, when some part of me was still ashamed of what had been done to me, that I was “molested” because the man who played skillfully with my 8-year-old penis, who put it in his mouth, who put his lips on mine and tried to push his tongue in as deep as it would go, did not anally rape me. … Instead of delineating what he had done, I chose “molestation” hoping that would convey what had happened to me.

Of course it doesn’t. For listeners to appreciate and understand what I had endured, I needed to risk that they will gag or rush out of the room. I needed to be particular and clear as to the details so that when I say I was raped people will understand what I truly mean.

Yglesias is right. Words can’t stop his boyhood suffering. But specificity is the first step to understanding it. Legally speaking, I’m not sure rape is the right word to use for this crime. Morally and viscerally, for a child who went through what Yglesias did, I know it is.