A Body by the Side of the Road

On the morning of April 16, 1995, a passerby reported a body, wrapped in strips of blue towel and lying by the side of the road, to the police in Irvine, Calif. It was a young man, dead. Bloody gashes covered his head, shoulders, back, and arms. His skull was cracked and two of his fingers hung from one hand, nearly severed. Forensic examiners later concluded that the wounds had been inflicted with a meat cleaver.

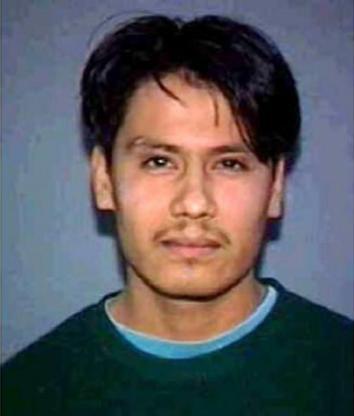

The police identified the murder victim as 25-year-old Gonzalo Ramirez and soon linked him to another crime report they had received hours earlier. At about 12:30 a.m., Ramirez and a friend, Noel Reyes, had left a dance club, El Cortez, in Santa Ana, the city next to Irvine. Ramirez had driven about a mile in his pickup truck when a white van rear-ended him at a red light. Ramirez pulled over to the curb and got out. From the truck, Reyes turned around and saw two men and a woman sitting in the van, he told the police. One of the men got out and started to punch Ramirez. Reyes rushed to help his friend, but the second man got out of the van and came toward him. Thinking he had a gun, Reyes turned and ran down the block for help. He found a security officer at a nearby Motel 6, but by the time they made it back to the intersection, Ramirez, the two men, and the van were gone.

Reyes told the police that he had no idea why the men in the van wanted to hurt Ramirez. He’d never seen them before, and he and Ramirez hadn’t had any trouble at El Cortez. The police spoke to Ramirez’s brothers, who told them he had three girlfriends, as well as a wife and two daughters in Mexico. But when the police interviewed the women, they turned up nothing suspicious. Then in the third week of May they got Ramirez’s phone bill and noticed another woman’s name written on the back: “Paty,” with two phone numbers, one marked “school” and the other marked “home.”

“I Thought He Was a Nice Guy”

Norma Patricia Esparza, a 20-year-old sophomore at Pomona College, was home in Santa Ana for the weekend when she met Ramirez. It was March 25, a Saturday night, three weeks before he was killed. Patricia had gone to El Cortez with her sister and a friend from school. Ramirez was there and asked her to dance. At the end of the evening, he asked for her phone number, and she gave it to him, “because I thought he was a nice guy,” she would later tell investigators.

Courtesy of Jorge Mancillas

Ramirez called the next morning and asked Esparza out to breakfast. She told him she could go if her sister, Juana, and her friend, Nancy Luna, came too. Afterward, Ramirez offered to drive Esparza and Luna the 25 miles back to Pomona, and they said yes. He dropped Luna off at her dorm and asked Esparza if she would show him around campus. He also wanted a drink of water. “I said, ‘Well, I have a lot of work, but sure,’” Esparza later told the police. “‘I have to drop my stuff off, so let’s just go up to my room.’”

Esparza had a single. Ramirez lay down on her bed and asked her to have sex. She said no. He insisted, saying she’d led him on. She told the police that she said to him, “You know, you have to leave, because I have to do my work.” Ramirez persuaded her to lie down next to him, and they talked for a bit, but when he tried to kiss her, she got up and asked him again to go. Instead, he started pulling off her clothes and she wound up on the floor. “We were struggling and I seriously don’t know how I ended up there,” she said. After he wrestled her pants off, she stopped trying to fight. “I figured it will be better for me if I pretend that, um, I’m going along with it,” she told the police. “I kind of just blanked out.”

Afterward, Esparza cried into her pillow. Ramirez asked if he could see her again. She said no, and he left. Esparza went the next day to see a college nurse and got a morning-after pill. She told the nurse she’d been “date raped,” but the nurse, according to what Esparza told investigators, didn’t suggest making a police report. Neither did a professor Esparza said she talked to about the rape, when she burst into tears as she tried to explain why she’d missed a deadline for class.

Esparza told one other person: Her ex-boyfriend Gianni Van. Esparza and Van had started dating the previous August. They met at the clothing store where Esparza was working for the summer when Van came in to pick up an order. He was the 25-year-old assistant manager of a shoe store in nearby Costa Mesa and had an interest in fashion design. He liked to surf and drove a sports car. Esparza and Van went on dates to the beach and the movies, seeing each other a few times a month until February, when Esparza broke up with him. She felt that Van was getting too possessive and she wanted to concentrate on her studies, she says.

In April, though, Van called and asked if he could come to Pomona to see her. He visited two weeks after the rape. When she opened the door, there were tears in her eyes. Van asked what was wrong, and she said she just wanted him to be there and comfort her. They spent the day together. That night, they both later told the police, Esparza finally told Van she’d been raped, and when he pressed her, she told him Ramirez’s first name.

“You Were a Victim”

On May 24, the day after seeing Ramirez’s phone bill with “Paty” scrawled on the back, investigator Ben Meza asked Ramirez’s roommate, Eloe Silva, if he knew who Paty was, the record shows. Silva said that a few weeks before the murder, toward the end of March, Ramirez had come home and told him that he’d been in the dorm room of a girl by that name. Silva had been lying on his bed, and Ramirez grabbed the cuffs of his pants and yanked them off. “That’s the way I took the pants off the girl I had sex with,” Silva remembered him saying.

Santa Ana Police Department

The phone numbers Ramirez had written on his bill traced to Esparza’s Pomona College dorm room, and to her family’s house in Santa Ana. On June 8, Meza and another officer went to talk to Esparza. The police asked if she knew Ramirez, and she said yes. She told them about the rape and also that she had confided in Gianni Van, her ex-boyfriend. The police asked Esparza if Van had gotten upset. “Yes,” she said, according to the transcript of the interview Meza conducted, but “he was just there for me.” Had he done anything to suggest he might retaliate? Esparza said no.

“Is Gonzalo dead?” she asked Meza, saying she’d noticed that he was from the homicide unit. He said yes. And then Meza continued, “If you know who killed him, this is the time for us to talk about it, because we don’t want you getting into something that later on you might not be able to get out of.”

Esparza said she had no more to offer. Meza kept pushing. Because of Ramirez’s wounds, he said, the killer “was somebody that would be very, very angry, and somebody that has a nice build like you, gets raped by this guy. … Don’t try and protect anybody.” A few minutes later, he continued, “Is there anybody you’re trying to protect? ’Cause don’t do that. … You were a victim, like I said, so I want to keep it that way.”

Esparza gave no new information. “I just get a feeling about you that you know more than you want to tell us, and you may be protecting somebody,” Meza told her. He asked if she would take a polygraph test. Esparza agreed, and Meza said he’d call her to make the arrangements. “I hope that you’re being completely honest with us,” he said before he left. “Because murder is the kind of crime that doesn’t go away. The investigation never stops.”

Courtesy of Jorge Mancillas

For 17 years, that warning barely echoed in Patricia Esparza’s life. She graduated from Pomona with a double major in psychology and women’s studies. She went on to earn a Ph.D. at DePaul University in clinical psychology. As a researcher, she focused on human resilience, studying how Latino and urban teenagers develop a sense of belonging and cope with loss and conflict. In 2007, she became a consultant on mental health to the World Health Organization in Geneva. By then Esparza had married Jorge Mancillas, a neurobiologist who had his own biomedical research lab at UCLA and taught at the medical school. In 2009, Esparza took a position on the faculty of Webster University in Geneva and gave birth to a daughter, Arianna. Mancillas started working at the Global Fund. They’d each been born in Mexico; now they were buying an apartment in a small French town near the Swiss border, installing a new kitchen, and settling down to raise their child.

And then the past charged in. On her way to an academic conference in St. Louis, in October 2012, Esparza was arrested at Boston’s Logan Airport for the 1995 murder of Gonzalo Ramirez.

The Night of the Murder

Until police handcuffed her at Logan Airport, Esparza says she had no idea that she was a wanted fugitive. Held for two months in an Orange County jail, she finally told police her version of the events leading up to Ramirez’s murder. Esparza was then released on $300,000 in bail and allowed to go home to France. In December 2012, prosecutors in Orange County brought murder charges for Ramirez’s killing against Gianni Van and two other suspects, Shannon Gries and Diane Tran. All three pleaded not guilty. (A fourth suspect, Diane’s husband, Kody Tran, died in July 2012.)

Esparza’s account of the events leading up to the murder helped lead to those indictments, and she came back to California repeatedly during the next year, for hearings and to testify about the murder before a grand jury. But cooperating did not set her free. Last fall, after she again returned to California knowing that her bail could be revoked, prosecutors presented her with a stark choice—plead guilty to manslaughter and accept a three-year prison sentence, or stand trial for murder.

Esparza refused the plea bargain. Standing before TV cameras outside the Santa Ana courthouse in November, 4-year-old Arianna’s arms wrapped around her and Mancillas by her side, she said of the manslaughter proposal, “I cannot accept because it would essentially be a lie.” Esparza, 39, described herself entirely as a victim: “I was terrorized,” she said of the night Ramirez was murdered. The next day, she went back to prison, where she is still awaiting trial. Her next hearing date is set for Feb. 26.

How did Patricia Esparza go from being a victim of rape to a murderer, in the eyes of prosecutors? The answer hinges on what happened the night Ramirez was killed. What Esparza didn’t tell the original investigators in 1995, but did recount in 2012, was that on the night of the murder, Van took her to El Cortez, on the chance of finding Ramirez there. By this point, she says, he was fluctuating between being kind and being angry—blaming her for the rape and saying that she must have wanted the sex to happen, she says. They went to the club with Kody Tran and Shannon Gries, friends of Van’s, along with Gries’ girlfriend, Julie Rojas, who also made a statement to the police in 2012. Esparza had never met Gries or Rojas before. She’d been briefly introduced to Tran and his wife, Diane, at their wedding reception (Van was Kody Tran’s best man). “I didn’t really know these people or what they were capable of,” she told me on the phone from prison.

According to Esparza and Rojas, Van and the other men wanted Esparza to show them the guy who had raped her, and when Ramirez walked by their table, she pointed him out.

Esparza says she felt threatened and intimidated by Van—and that she was particularly ill-equipped to deal with those feeling because for years, as she has said publicly since she was charged, she was sexually abused by her father. “For a very long time it was very difficult for me to travel back into that moment,” she told me about that night at El Cortez. “I really struggled a lot until I talked to a psychiatrist last summer. I was able to describe my emotions and he gave me perspective that made a lot of sense to me. When you’ve been abused for years by your father, it doesn’t take a lot for you to feel threatened. Gianni was bullying me about the rape, and I wasn’t necessarily thinking about what would happen at any later point in time. The psychiatrist said when you’re in survival mode, your ability to foresee the next step, to think about consequences, stops working. That’s consistent if you read about trauma. It’s been 18 years, and honestly this part is blurry, but as far as I know all that I thought was: ‘This man is on me and I need to get him off.’” As for what Esparza expected Van would do to Ramirez, last year she told the grand jury that she thought, “the worst that would happen is that he would rough him up.”

She left the club with Van, in a car that followed Kody Tran, Gries, and Rojas, who were in the white van. When the van hit Ramirez’s truck, and the men got out and went after Ramirez, Esparza says she was taken completely by surprise. “Not in my wildest dreams did I expect that Gonzalo Ramirez was going to be pulled into a van,” she said. Rojas got out of the van and drove Esparza away in the car, they both told the police.

About an hour later, Rojas and Esparza say, Van summoned them to Accurate Transmission, an auto shop owned by Kody and Diane Tran. Esparza was taken upstairs, where she saw Ramirez hanging by chains from the ceiling, beaten and bloody. She told the police that he said to her in Spanish, “I don’t know you, little one.” Diane Tran was at the shop too, and when she also spoke to the police in 2012, she said she saw Ramirez, covered in blood, and heard him speak a few words in Spanish. Rojas, who says she stayed downstairs, told the police she heard Esparza scream, “crying that it wasn’t him.” Van and Kody Tran apparently didn’t believe her. According to Rojas and Esparza, they used the sight of Ramirez’s tortured body to warn the women against ratting them out: This is what will happen to you if you screw us.

Esparza says she shut down, falling into a pattern of fear and submission instilled in her by her experience of abuse as a child. “I felt I needed to submit to survive,” Esparza told me. “I’d been broken by the years of abuse by my father. I couldn’t assimilate so many traumatic experiences. I felt utterly trapped.”

“A Very Sophisticated Defendant”

How much responsibility does Patricia Esparza bear for the death of Gonzalo Ramirez? Does her fear and paralysis excuse her, or should she spend years in prison for failing to save the man who raped her? I’ve read thousands of pages of law enforcement records in this case and spoken to as many of the people involved as I could find. Esparza is not blameless, as her own account makes clear. She missed repeated chances to go to the police and tell the truth, including after she saw Ramirez hanging by those chains in the hours before he was killed. But I see no evidence in the record—none at all, from any other suspects or witnesses—that she intended his murder or helped plan it. And yet: Esparza is facing life in prison.

Later that night, Esparza says Van drove her home and told her that the men had let Ramirez go. When Meza, the investigator, interviewed her two months later, and she learned of the murder, she was still too scared of Van and his friends to tell the police what she knew, she says. “I wish I had,” she told me. Five days after they talked to Esparza, the police questioned Van and Kody Tran, who then came up with a plan: Esparza would marry Van so that she wouldn’t have to testify against him, because of the rule of spousal privilege, which allows one spouse to refuse to testify against the other. It sounds like a Law & Order episode, but the next day, Esparza and Van drove to Las Vegas and got married. “They told me I had to,” Esparza says. “I felt confused. I couldn’t think.”

With her strange story—and the puzzle of whether she is victim, victimizer, or both—Esparza, small-boned and less than 5 feet tall, has become the subject of a spate of press coverage, including a Today show appearance from prison. Thousands of people have signed a Change.org petition calling for her release and praising her as a model of resilience and accomplishment. They leave notes like this one from Lauren Roux of Coppet, Switzerland: “I only know Dr Esparza in a professional capacity but she has been instrumental in helping my 14 year old son with his learning difficulty with working memory. I hold Dr Esparza in the highest regard.” Caroline Heldman, a politics professor at Occidental College who co-founded the group End Rape on Campus, sees Esparza’s case as “a classic story of institutional betrayal.” By prosecuting her, the Orange County District Attorney’s Office “is sending a chilling message to survivors that they will not be believed.” Heldman’s defense of Esparza is particularly compelling now, as, decades after Esparza’s college rape, the problem of campus sexual assault has finally captured public and government attention.

On the other side, and with equal vehemence, are the Esparza skeptics, some of whom point out that she is “always accusing others for her plight.” Or that she is playing the victim for her own gain: “Okay, this is a terribly sad story, but is it believable?” a criminal profiler blogged. The chief of staff for the Orange County District Attorney went further. “She’s a very sophisticated defendant,” Susan Kang Schroeder told the Pasadena Star-News. “She has a Ph.D. in psychology and she knows how to play on people’s emotions, including the use of her 4-year-old daughter as a prop at the press conference. This is a woman who is trying to act like the victim in this case when the real victim was brutally murdered and the case went unsolved for 20 years.”

Screenshot courtesy of NBC

By refusing to plead, Esparza says she is finally standing up for herself. “I (we) took a decisive step in ‘defining and defending’ what is just, unjust, right and wrong. That was the start of a journey,” she wrote from prison about her decision not to accept the manslaughter charge, on Set Patricia Free, the website Heldman and other supporters set up on her behalf. However determined she may feel, this is a hugely risky journey, given the long sentence Esparza faces if she’s convicted. Along with all the tangled questions her case raises about victimhood and culpability, it also demonstrates the massive power prosecutors have to pressure defendants to plead. According to recent numbers, 94 percent of state felony convictions arise from guilty pleas. Prosecutors routinely use the threat of high sentences to leverage those pleas and manage their workloads. “We’ve granted extraordinary power to prosecutors in our system of criminal justice,” says Richard E. Myers II, a law professor at the University of North Carolina and former assistant U.S. attorney.

The discretion to bring serious charges is especially broad in cases of group conspiracy. It’s routine and even necessary, Myers argues, to hold every defendant accountable for the group’s wrongdoing, in order to flip some into testifying against the others. “Think about getting members of al-Qaida to turn on each other in a case of group criminal activity,” Myers said. This kind of prosecutorial authority “is a powerful tool that can be used for good. Or, sometimes, it can be used for evil.”

So is this what prosecutors are doing—upping the charge against Esparza in order to get her to talk, to help their case against Van and the others? The Orange County DA’s Office says no. After all, Esparza has already told the police her story of the events leading up to the murder. She’s been charged for Ramirez’s killing, prosecutors say, because “there is sufficient evidence to prove she is guilty beyond a reasonable doubt of that charge.” When I called Schroeder and asked her to elaborate, she said, “If you know someone will be murdered, and you aid and abet by pointing him out beforehand—that’s participation. We have the evidence to show that when she pointed him out, she knew Gonzalo Ramirez was going to be killed.” What evidence? Schroeder wouldn’t say. Last Thursday, I sent this question along with several others to the spokeswoman for the Orange County DA’s Office. I asked to talk to lead prosecutor Michael Murray (or anyone else who could answer my queries). The spokeswoman said she would try to put me in touch with Murray, but despite my repeated efforts to follow up by phone and email, she did not do so nor did she answer any of my questions.

I’ve read through all the police interviews with the other witnesses and suspects, and none of them say that Esparza knew Ramirez would be killed beforehand. Thinking that the man you say raped you could get “roughed up” is very different from thinking he’ll be murdered. Maybe the prosecutors just don’t believe her. But given the lack of evidence that she’s lying, I can’t help but wonder if they are punishing Esparza for keeping quiet all those years—especially because they may well have botched the case to begin with, as the initial effort to crack it slipped away.

The Case Against Gianni Van

When investigator Ben Meza interviewed Gianni Van on June 13, 1995, five days after he talked to Esparza, Van backed up her account. He and Esparza had dated a few times a month, beginning the previous summer and continuing through February. In the first half of April, he’d gone to see her at Pomona and could tell that she was upset. When he asked what was wrong, she said she just wanted him to be there and comfort her. Late that night, she finally described the rape and told him Ramirez’s name. “I was totally devastated,” Van told the police. “I was really mad.” He urged her to go to the police, but she said “‘No, that’s it, just leave it like that,’” Van said.

Santa Ana Police Department

Meza and his partner also asked Van about a Chevrolet van that was registered in his name, and he told them it actually belonged to his friend Kody Tran, who owned an auto shop, Accurate Transmission, in nearby Costa Mesa. Tran had asked Van to register the vehicle because he was facing a methamphetamine charge. The police went to Tran’s shop later that day. They saw a white Chevrolet van parked outside. Tran said it belonged to him, and that Van borrowed it sometimes and also had a key to the auto shop. Meza noticed blue roller towel in a dispenser, much like the towel they found Ramirez’s body wrapped in. Had Tran ever noticed that he was missing an extra roll? Tran said that actually he thought the vendor had left two rolls in mid-April and that he only remembered using one. He wasn’t sure what had happened to the other one.

Tran let the police search the van and the shop, and they took DNA samples from bloodstains on the floor and the walls, which Tran said were probably from his employees. A week later, the police talked to the towel vendor, who told them he’d left a roll at Accurate Transmission on April 11, but afterward, Tran had called to ask him where it was. That missing roll had never been accounted for, the vendor said. The police also went to look at Ramirez’s pickup truck, which was blue. There was a dent on the rear bumper and a patch of white paint.

In January 1996, the results from the DNA analysis came back—with a match for Ramirez. His blood was on a wall in the office of Accurate Transmission. The police went back to Reyes, Ramirez’s friend who had been in the truck with him the night of the murder, to show him pictures of Kody Tran, Gianni Van, and two of their friends. Reyes recognized none of them. But he did remember that one of the men he saw wore his black hair in a long ponytail. Van wore his hair the same way.

On March 6, 1996, the police interviewed Van again. He stuck to his story: He’d “respected Norma’s wishes to forget the alleged rape incident.” (Esparza goes by both Norma and Patricia.) On March 8, Van was arrested and charged with murder.

Esparza was in Kenya on a student exchange program when Van, her then-husband, was arrested, and the police didn’t contact her there. They turned their attention to another potential witness or suspect: Shannon Gries. He’d worked at Tran’s auto shop in 1995 after getting out of jail for meth-related crimes. Gries matched the description for the first man Reyes had seen come out of the van—blond and tall, with a heavy build. Gries had been using an assumed name because there were warrants out for his arrest (more drug charges). He said he knew nothing about Esparza’s rape or Ramirez’s murder. The police asked him who else worked for Tran at the time of the murder, and he mentioned his girlfriend, Julie Rojas. “She was like the secretary,” he said. “We both got fired ’cause we both did drugs. Now she’s locked up.”

The police didn’t interview Julie Rojas. They also didn’t talk to Diane Tran, though she co-owned Accurate Transmission with her husband. They did go to see Esparza again when she got back from Kenya. A new detective, M. Dominguez, conducted the oddly incomplete interview. He asked Esparza to go over the facts of the rape again—how she met Ramirez, why she let him into her dorm room, and how he assaulted her. Dominguez also asked whether Esparza went to church regularly and if she and Van had ever had sex. When she said yes, he pressed for details about when and where. “How is that relevant to anything anyways?” Esparza asked.

Dominguez didn’t ask Esparza about her marriage to Van—if he had, he might have learned that they didn’t live together and were in touch only sporadically. The investigator also didn’t follow up on Esparza’s offer to take a lie detector test, which the original investigator, Meza, had also dropped. And Dominguez never sounded her out about testifying against Van. In California, and under federal law, the spousal privilege meant she—not Van—could choose whether she would testify. (I tried to reach Dominguez, but the Santa Ana Police and the Orange County District Attorney’s Office would not let me speak to him or any other officers who worked on the case because it is pending.)

Inexplicably, instead of continuing to build their case against Van, the police and prosecutors at the time just let it fade away. The murder charge against him was dropped. When I asked Schroeder why, she cited “insufficient evidence.” (She also said that Van had merely been arrested rather than charged. This is also what the Santa Ana police told the Orange County Register. But the record includes a charging document.) I asked the spokeswoman for the Orange County DA about this, but as I mentioned, she didn’t answer my questions. I also asked the Orange County District Attorney from 1996, Michael Capizzi, about the decision to drop the charges against Van at that time. “It may be hard for you to believe that there are jurisdictions more heavily populated than Manhattan,” he wrote back. “I have no recollection of the nearly 20 year old case to which you refer.”

If the police had asked Esparza more searching questions in 1995 and 1996, could they have unraveled the remaining facts of the murder—and convicted Van, Kody Tran, and Shannon Gries? After all, they had Ramirez’s DNA in the auto shop and other pieces of the puzzle, and they’d found the chief suspects. If they’d learned more about Esparza, could they have figured out why she felt trapped by fear, and how to break through it?

“Shutting Down Was the Only Way to Deal”

Esparza was born in a village without running water in southern rural Mexico. When she was five, she moved to Santa Ana with her mother; her older sister, Juana; and her younger brother, Rodrigo. There they joined her father, who’d gone to the U.S. earlier to work in a factory. Esparza has two other younger brothers who were born after the move. As the kids grew up, her mother worked long hours at different jobs—making wreaths and floral arrangements at an orchard during the weekdays, cleaning offices as a janitor in the evenings, and cleaning houses on the weekends. “We used to go with her to clean,” Juana told me. “My mom worked very hard and gave us everything she had.”

Courtesy of Jorge Mancillas

Esparza says her father started abusing her soon after she came to California and continued until she was 12. Like many children who are molested, Esparza told no one. “She couldn’t go to her mother because her father beat her mother,” Mancillas, Esparza’s husband, told me. When I spoke to Juana, Rodrigo, and Esparza’s mother, they all said the abuse occurred. (I tried to reach Esparza’s father through Rodrigo, but he declined to talk to me: Rodrigo said that while his father feels terrible about what he did, he is afraid to discuss it publicly.)

Juana said that when she was 13, her father tried to molest her, too, and she did speak up. That was when she and her mother learned what was happening to Patricia. “We were in shock,” Juana said. Despite the revelation, Patricia’s father kept living with the family. “They didn’t know what to do with that information,” Esparza said of her mother and sister in a video made by a family member in the days before she went back to prison last November. “They didn’t know how to be there for me.”

Esparza retreated into books. Shy and quiet at home and at school, her family and friends say, she would wait on the corner each week for Santa Ana’s mobile library. One favorite: A Tree Grows in Brooklyn, the 1943 classic about a girl from a poor immigrant family who, too, is threatened by sexual abuse and loves to read. “My home was chaotic in many senses,” Esparza told me from prison. “It was the home of a working-class family just struggling every day with putting bread on the table, and working to raise five children. One way I survived that chaotic upbringing was finding other worlds I could connect with, through books. A Tree Grows in Brooklyn is the story of a girl whose family is also struggling, who escapes her harsh reality through reading and education. I could relate so well to her. I felt, a tree does grow, and I can make something grow, too.”

Courtesy of Jorge Mancillas

In middle school, Esparza started running track. Her academic and athletic prowess brought her to the attention of a counselor who was recruiting for a program called A Better Chance that helps private schools recruit students of color. In eighth grade, Patricia and a friend of hers both found out they’d been accepted to Phillips Exeter Academy on scholarship. “I was so excited and wanted to share my happy news with everyone,” her friend, who asked me not to name her because of the charges Esparza is facing, wrote to me in an email. “I looked over at her and she seemed so calm and composed. She always knew how to contain her emotions.”

At Exeter, with its tony campus, wealthy student body, and cold weather, Esparza and her friend “clung to one another for emotional support,” her friend wrote. Sometimes they curled up together on a sofa in the common room of a dorm and whispered in Spanish. “I loved listening to them,” Susan Peterson, another classmate told me. Peterson said that Esparza studied hard but also branched out. She joined the cross-country team and went on a semester abroad program in Barcelona, Spain, during her junior year. “She was extremely driven to get the most out of it,” Peterson remembers. “Academically, yes, but also, in Spain, she went to every museum, she did everything. She was not an in-your-face kind of person at all, but throughout high school it was like she was saying to herself, ‘This is my shot. I’m gonna do it.’”

Juana says that after Esparza left for Exeter, they weren’t close, but she could see her sister’s determination. “I think seeing my mom made her strong,” Juana said. “She wanted to do more than my mom did in life.” That’s a standard narrative of ambition for a child of immigrants—fueled also, for Esparza, by her desire to escape from her past with her father. She tried to avoid him whenever she went home, her brother Rodrigo told me. And at Exeter, only her close friend from home knew she’d been abused. She learned to lock away painful experiences, to repress the memories in order to succeed.

Looking back, Esparza says now that, “shutting down was the only way I could deal with the harrowing experience” of being abused, when “I felt utterly helpless and just unable to protect myself.” As a psychologist, she has clinical terms for this: post-traumatic stress disorder and disassociation. But when I asked if she can entirely distance herself from her own experience, she said no. “You never escape the sensory memory—that visceral sense of being persecuted in your own home, of being under threat, of knowing there is no safe corner. No matter how much professional training I have, I can’t cure myself of that physiological reaction. You’d think I could overcome that, but it doesn’t get easier. Even now, just articulating it for you, I can feel my heartbeat and I’m starting to shake a little bit because I’ve been a master of tucking things away and compartmentalizing to survive. I did that as a little girl and I do it even now.”

Is this also how Esparza moved on from the horror of what she’d seen on the night of Ramirez’s murder, and from her own failure to go to the police or tell them the truth afterward? Or perhaps that’s not it at all; maybe she couldn’t shake the memory of Ramirez, beaten and bloody, hanging from the ceiling. Maybe she was just scared. When I asked Esparza about this, I heard a sharp intake of breath on the other end of the phone line. “For months afterward I thought I was going to die of panic,” she said. “These people—I’d learned they were violent, and I just felt that I was under threat. In danger. To have that happen again, in such an acute and horrible way, after what I’d experienced for all those years at home—I’m really surprised that I didn’t fall to pieces, and that I was able to continue. But I did.”

Esparza never lived with Van. But in the months after the murder, he and Tran kept tabs on her, she says, by calling her and showing up at her family’s house. “It was a way for them to control me,” she says. (Through his lawyer, Van declined to comment.) She got away from Van after she graduated from college and went to Chicago for graduate school. She couldn’t shed her fear, though: He knew where her family lived. And they remained legally tied by their marriage.

And so when Jorge Mancillas fell in love with Esparza and proposed to her in 2001, after dinner at the Windows on the World restaurant at the top of the World Trade Center, Esparza at first said yes—and then later broke down and told him she couldn’t do it. “She started shaking. I’d never seen her like that,” Mancillas told me. “She said we could still share our lives and be together, but she was already married—it was a forced marriage, and she’d never lived with the guy, but she didn’t want me to ask her anything about it, because she said she didn’t want to put me at risk.”

Courtesy of Jorge Mancillas

Mancillas says it didn’t make sense to him, but he stopped pushing her to explain when he saw how much it upset her. Instead, he put her in a touch with a lawyer friend of his, Leonard Weinglass. “He talked to her and told me, she’s right, it’s better for you not to know,” Mancillas says. Weinglass offered to try to arrange a divorce, and in 2004, Van agreed. Weinglass was able to obtain his signature for the divorce, and Esparza brought it to a judge in Chicago who signed off. “Good luck to you,” the judge said in parting, according to the transcript of the divorce hearing. Mancillas saw Van’s name on the divorce order, Googled him, and found nothing—no online record of the 1996 prosecution. Without any more to go on, Mancillas decided that Esparza’s family must have arranged a marriage for her to pay off a debt—“I thought it had to be something back in Mexico,” he says. “Lenny told me to trust Patricia. He said, ‘Go on with your life.’” They did, moving to Europe and climbing in their respective professions. They were an immigrant dream couple, and they thought they were free.

“What If”

In 2010, a pair of new Santa Ana detectives, Dean Fulcher and Frank Fajardo, launched a new chapter in the investigation of Ramirez’s murder. When I emailed Fajardo to ask why, he put me in touch with the public affairs officer for the Orange County Police, who would only say the police had “new leads” at the time. But I can’t find any new evidence from that moment in the record. Maybe Fulcher and Fajardo were just interested in this old case. They did know that Esparza and Van had divorced, and that she no longer had a marital privilege to assert if she wanted to avoid testifying. Fajardo found her online and emailed her in September 2010: “I merely wish to speak with you regarding the incident, which occurred in 1995,” he wrote after introducing himself. “I hope you believe me when I tell you that you are NOT a person of interest NOR ARE YOU A SUSPECT in this case. … You hold vital pieces of this puzzle and I hope you choose to help me.” (The bolding is his.)

Esparza sent the detective’s message to Weinglass, who offered to talk to Fajardo on her behalf. After that conversation, Weinglass emailed Esparza counseling caution about talking herself to the police. Fajardo, he said, seemed interested in information she had already given the police in 1995 and 1996—specifically, about what she had told Van about Ramirez. “My impression is that they’re not being totally honest with us and that this could become a kind of cat and mouse game where they’re seeking more than they let on,” Weinglass wrote.

Weinglass didn’t try to make a deal for Esparza—like immunity from prosecution in exchange for her full story of the events leading up to the murder. Instead, he wrote back to Fajardo saying that Esparza had already provided the police the information they now sought. “Hopefully, this answers your question and no further effort will be necessary to have her repeat what she has already twice said before,” Weinglass wrote. “As you can well imagine recalling these events is very stressful to her. She is now a married woman, a mother, a professor and a resident of Europe. There is no intention here to impede your investigation; but, as you may well imagine, it’s my obligation as her attorney to curtail any unnecessary intrusions into her new life.” Weinglass died a few months later. Mancillas, meanwhile, says that while he knew the police wanted to talk to Esparza, she and Weinglass still wouldn’t tell him why. In hindsight, it’s hard to believe or understand—for Mancillas, too. “In retrospect, now that I know the whole story, I think, how could I have not pushed?” he says. “I feel terribly guilty.” But he trusted Weinglass, and the police inquiry coincided with a difficult period for him at work. “I was pulled by external demands,” Mancillas told me, his voice breaking. Later, he emailed, “As I looked back at the last few years, I have just been unable to put aside that most corrosive of thoughts: what if?”

Esparza had missed her second chance to help the police solve this crime—and to bring to justice the men she now says committed a terrible murder, not to mention psychologically tormented her. “I was still scared of those people,” she says. She pointed out that Fajardo himself suggested in his initial email that they were dangerous. “The person I am investigating has possibly committed the same type [of] crime again,” he wrote. That wasn’t true of any of the suspects, as far as I can tell. But the line made Esparza think that “even though I was far away, my family could still be at risk.” Still, she added, “I wish now that I had resolved this then.”

Her decision to keep quiet, based on her lawyer’s bad advice, clearly didn’t help her standing with the police. “Several attempts have been made to interview Norma Esparza to clarify information developed in the ongoing investigation, both in person and via the telephone,” the detective who issued the warrant for her arrest in October 2012 wrote. “Esparza has refused to make herself available to be interviewed.” The warrant also cited one new witness: In December 2010, the police had talked to Nancy Luna, the Pomona friend who had gone with Esparza to El Cortez the night she first met Ramirez. Luna told investigators that when she asked Esparza about Ramirez’s death in 1995, after learning of it, Esparza told her about going back to the club in April with Van and his friends and pointing out Ramirez to them. Luna didn’t suggest that Esparza intended to have Ramirez killed, but she did link Esparza to the chain of events that ended with his death.

Courtesy of KCBS/KCAL TV

While Esparza sat in jail in the fall of 2012, she and Mancillas remained optimistic about negotiating a deal that would not include prison time nor accepting culpability for the murder, which they thought would ruin her psychology career. At that point she had two lawyers: Peter Schey, another friend of Mancillas’, and Isabel Apkarian, a public defender. At first, Schey was in touch on his own with the prosecution, angling for an agreement in which Esparza would plead guilty to a relatively minor offense, like obstruction of justice, in exchange for her testimony. Schey told me he thought he and lead prosecutor Michael Murray were close. But then Schey mentioned, as a “small gift” to Murray, Mancillas says, that Julie Rojas, Shannon Gries’ girlfriend, had driven Esparza away from Ramirez’s kidnapping. Schey thought he’d done nothing wrong, given that Rojas’ name was already in the record. “I’m certain that none of the steps that I took were to her disadvantage,” he said of his representation of Esparza when I called him. (Schey had permission from Mancillas to speak to me.)

But Apkarian thought the opposite, according to Mancillas. (She declined to comment for this article because of attorney-client confidentiality.) She told Esparza and her husband, they say, that Murray was now saying that since he could get Rojas to talk, based on what Schey told him, he didn’t need Esparza’s testimony. (And since all the investigators may have known before this was that Rojas had worked at the auto shop, Apkarian’s concern appears well founded.) Apkarian told Esparza and Mancillas to stop talking to Schey. And then, Mancillas says, Esparza was rushed to talk to investigators before Rojas did. This, too, reduced Esparza’s bargaining power. On Dec. 6, 2012, Esparza gave the police a two and a half hour statement about what she knew related to the murder.* But while Apkarian ensured that Esparza’s statement to the police could not be used against her, she did not secure full immunity from prosecution or a promise that Murray would reduce the charges.

The police interviewed Rojas the same day. As it turned out, she sounded like she would make a terrible witness, though that hasn’t helped Esparza. She had a lengthy prison record, including convictions for theft, burglary, assault, and possession of methamphetamine, stretching from 1991 to 2009. She said that she was using meth and drinking on the night of the murder and that she’d gone back to prison shortly afterward. She didn’t recognize Van in photos the police showed her. About the events leading up to the murder, she backed up Esparza’s story, saying, “The girl did say that she got raped, okay. And so we all went out drinking that night and, uh, so she could point out somebody that raped her.” She took Esparza to a bar after they drove away from the kidnapping, and then an hour later to the auto shop when Van called. She stayed downstairs, she insisted, so she didn’t see Ramirez, but she heard Esparza cry and scream that it wasn’t him. “I was scared to death,” she said when the police asked why she didn’t come to them when she learned Ramirez had been murdered a day or two later. “Nobody came to talk to me,” she pointed out. “I would have told them.” In exchange for her promise to testify now, Rojas was granted immunity.

Santa Ana Police Department

The next day, Dec. 7, the police arrested Diane Tran. She and Kody had begun divorce proceedings in 2008, and she’d gotten a restraining order against him. He’d violated it in July 2012, by coming to the house where she lived with their two teenage sons and locking himself in a bedroom. When a SWAT team arrived at the scene because of reports that Tran had a gun, he shot and killed himself. After she was arrested that December, Diane Tran told the police she was ready to talk about Ramirez’s murder—and confessed that she’d known about the plan to kidnap him days before it happened. She said that Van came to Kody Tran upset about the rape, and the two of them, on their own, decided to beat up Ramirez. That night, she’d gone to the auto shop to see Ramirez “out of curiosity,” and said she thought Van intended to kill Ramirez at that point. The next day, Kody told her that he, Gries, and Van drove Ramirez down a nearby hill, and Van got out and used a knife to kill him. When the police asked Tran why she hadn’t come to them earlier, she said. “I guess it was just my thought was, ‘You know what? … it’s not my problem.’”

Last month, Diane Tran pleaded guilty to manslaughter and got a four-year prison sentence. “It’s a terrible blow to her, but out of love for her teenage sons, and given the vagaries of our legal system, she removed the possibility of a life sentence without parole,” her lawyer Robert Weinberg said. Van and Gries have each pleaded not guilty to the murder charges they face. Van’s lawyer, Jeremy Dolnick, said the evidence against his client comes from Esparza and other witnesses who “lack credibility.” Van, he said, has no criminal record. “He’s a short, quiet, unassuming guy. There’s nothing gangster-ish about him.” Gries’ lawyer, James Crawford, said of the prosecution: “They don’t have any real or competent evidence to connect Shannon Gries to the commission of the offense. All they have are these accomplices trying to save their own skins.”

Santa Ana Police Department

Crawford also called Esparza “the most culpable of them all,” telling me, “She’s the one who alleged that the victim raped her. She started the ball rolling. But for her, nothing would have happened.” That took my breath away, but in a stark sense, it’s true. Of course, there is nothing wrong with seeking comfort after being raped. Whether to blame Esparza for telling Gianni Van about the rape depends entirely on her motivation. The same is true for her decision to point out Ramirez to Van and his friends when they went back with her to El Cortez. Was she setting Ramirez up? Or was she a traumatized young woman who didn’t see the level of violence coming? Legally speaking, what comes into play here is called the “natural and probable consequences doctrine.” In most states, including California, when a crime involves another person, or a group, you’re responsible for the criminal actions of others if those actions are a natural and probable consequence of your own. In Esparza’s case, the answer to that question turns almost entirely on the answer to this one: Do you believe her?

Two Victims

In the local press, prosecutors have made Esparza sound untrustworthy by saying that “she wants to try this case in the media,” as well as insinuating that she is skilled at playing on emotions. The Los Angeles Times has pointed out that “according to court records, she has changed some details of her story” since she was arrested.* I asked Mancillas and Esparza about this, and they said they cannot publicly explain the discrepancies without jeopardizing the only kind of immunity she has, which is that her statements to the police and the grand jury can’t be used against her in court.

The inconsistency may undermine Esparza’s credibility, but I believe what I know of her story. That’s mostly because of the evidence and the fact that other witnesses have backed up each part of her account and contradicted none of it. But it’s also because her reactions to the rape and its fallout seem plausible. “She had no experience, nothing at all—no, no, no,” her sister Juana said when I asked her to help me understand how Esparza could have trusted Van or Ramirez. “She just went to Exeter, and then to college, studied, went back home. She was not the type of person who went out to nightclubs. I was the one who invited her to go out that night. She didn’t have a lot of friends at all. She just stayed home.” Gianni Van was the second boyfriend Esparza ever had. He seemed normal enough, Juana said. “I didn’t hang out with people who owned guns, with people who were violent,” Esparza said. “I was just so unprepared.”

At 20, in a moment of vulnerability and distress that harked back to her childhood experience of abuse, Patricia Esparza missed the warning signals Van and his friends must have sent that night. However wretched and unfortunate, that doesn’t seem especially surprising to me. In reporting this story, what has surprised me is the number of people who don’t believe Esparza at all. She wasn’t raped, I’ve seen asserted in comments online and heard as speculation from lawyers for the other defendants. (Pomona has added to these conjectures by disputing aspects of Esparza’s account, according to the Pasadena Star-News, saying that if she had reported a rape to the campus health center, the college would have alerted the police.) Update, Feb. 11, 2014: Pomona spokeswoman Cynthia Peters now says that while according to current policies, the health center would alert the campus police to a date-rape report, the health services records don’t go back to 1995, so it’s entirely plausible that Esparza is telling the truth about this.

Or if she was raped, then she was the one who connived to make Van and his friends carry out the revenge killing. Never mind that none of them—not Van, not Rojas, not Tran, not Gries—have implicated Esparza in planning the murder, according to the record I’ve read, even though that version of the story would serve their own interests.

Photo by Bruce Chambers/Orange County Register/AP Photo

Maybe Esparza is a figure of so much suspicion because it’s hard to square the 20-year-old she says she was—a young woman whose judgment was obliterated by fear—with the 39-year-old articulate professional she has become. Esparza is not always her own best advocate on this front. If she’d come clean in 2010, based on better legal counsel, and tried to right this old wrong from her past by telling the police the whole truth, she might have spared herself the ordeal of her arrest and prosecution. And by emphasizing the degree to which she has been a victim, she sometimes seems to lose sight of the greater magnitude of Ramirez’s suffering and death.

But in her husband’s presentation of her case, that thread of awareness is there. “There are two victims in this case, Gonzalo Ramirez, an older married man who preyed on young women and raped Patricia, but did not deserve to die for it, and Patricia, who did not deserve to be raped and then intimidated and terrorized by Van and his friends,” Mancillas wrote in the petition for her release on Change.org. “Yes, absolutely, we were both victims,” Esparza told me from prison. She pointed out that she could have fought extradition rather than talking to the police in 2012. “I could have said, ‘I’m staying quiet, prove what you can.’ But I didn’t because this is my chance to finally put all of this behind me and to bring about justice for this man who was killed. It hasn’t gone as I’d hoped but I still think that is right.”

Does not coming clean in 2010, or in 1995, make Esparza guilty of murder? I don’t see how it could. It’s evidence for a charge of obstruction of justice, not for criminally punishing Esparza for Ramirez’s killing. That’s the plea bargain that matches the record I’ve read and the reporting I’ve done, and given the months Esparza has spent in prison, she has already served enough time for an obstruction offense. The criminal justice system forces a choice between guilt and innocence. But for the system to achieve justice, prosecutors have to set the terms straight, by bringing charges that reflect actual culpability. Stretching the law to call Patricia Esparza a murderer doesn’t accomplish that. It’s just one more injustice in a series that stretches back for almost 20 years.

Correction, Feb. 10, 2014: This article originally stated that the police interviewed Patricia Esparza on Dec. 5, 2012, and that Julie Rojas was interviewed the next day. They were both interviewed on Dec. 6, 2012. (Return.)

Correction, March 4, 2014: This article also originally said that prosecutors have pointed out in the local press that Esparza has “changed some details of her story.” In fact the reference to this in the Los Angeles Times, which the sentence links to, comes from court records. (Return.)