In 2011, Oklahoma passed a law making it harder for doctors to prescribe abortion-inducing drugs. Oklahoma’s Supreme Court struck down the law as unconstitutional. Then the Supreme Court agreed to review the case, but asked the Oklahoma court (which had written only a few paragraphs) to clarify why they struck down the law in the first place. This week, the Oklahoma Court explained itself: The state’s effort to regulate abortion-inducing drugs amounted to a total ban on medication abortions. And so it was unconstitutional.

One day earlier, a lower court in Texas, looking at a substantially similar (but not identical) effort to regulate medication abortions, upheld the provision, albeit with an exception. If a woman need a nonsurgical abortion to protect her health or life, she can still get it. The raft of new efforts to regulate medication abortions are confusing, and the legal questions surrounding them are even more so. How can we square what happened in Texas with what happened in Oklahoma, and what does it all mean for the future of this type of abortion at the Supreme Court, where the Oklahoma case may be heard in the near future?

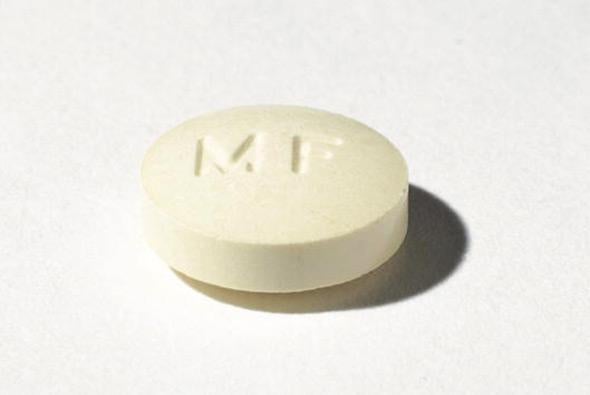

The constitutional questions around medication abortions are new and complicated and different from the usual fights we’ve witnessed over surgical abortion and TRAP laws (Targeted Regulation of Abortion Providers). Medication abortions mainly involve the drug mifepristone, or RU-486. They take place in the first trimester—and that means the state-erected limits are often thinly disguised state efforts to challenge what remains of Roe v Wade. Oklahoma Gov. Mary Fallin, signing her state’s bill in May 2011, called it “a critical part of our effort to promote the cause of life.” Gov. Rick Perry has expressly stated that his goal is to make abortion at any stage “a thing of the past.” In effect, these challenges force questions that have been unanswered for years at the court: Is Roe still on safe ground? Are state efforts to force the question back before the high court going to pay off? And what does it mean when courts seem to find it easier to write about the rights of doctors to practice good medicine than the rights of women to receive it?

Twelve states, including Oklahoma, have some form of medication-abortion regulations on the books. The Oklahoma ban was incredibly poorly drafted, essentially sweeping in any “abortion inducing medication,” which made it easy for the state Supreme Court to see it as a total ban. The other states have been sneakier.

As Linda Greenhouse explained in September, the issue here is not the abortions themselves. The statues revolve around how doctors may prescribe the series of pills that induce them. Only one drug—mifepristone—has been approved by the FDA for inducing abortions, and only for the first nine weeks of pregnancy. But the way doctors use this drug and others related to it has changed in the intervening years. At this point, the most common medication-abortion protocol requires that women take two pills: mifepristone, which terminates the pregnancy, and misoprostol, two days later, which causes the uterus to expel the pregnancy. In most states, women can take the first pill at her doctor’s office and the second pill at home, which helps improve access for poor or rural women who live far from abortion clinics, can’t take off several days from work, and want to terminate as early as possible.

Under the 2011 Oklahoma law, the state required physicians to follow the dosage and procedures only as written on the F.D.A. label. The prohibition on allowing doctors to prescribe the pill in a manner considered “off-label” effectively means that although research and best practices have evolved (as they have for medications approved for cancer and migraines and most other things), physicians must continue to prescribe dosages that are medically outdated. As Amanda Marcotte explained in Slate, since the FDA label was approved, further research has shown that the second pill in the series can safely be taken at home, and that the 600 milligrams of Mifeprex required by the label is too high. Most doctors agree that only 200 milligrams are needed. Finally, as Greenhouse clarified, “While the original F.D.A. label specified that the drugs should be used only up to 49 days of pregnancy, doctors have found the regimen safe and effective for up to 63 days—nine weeks of pregnancy.”

To sum up, the FDA label mandates a protocol that is more cumbersome, expensive, and dangerous for most women. Emily Bazelon explained why FDA reauthorization has not been sought, even though, at this point “96 percent of all medication abortions now involve an evidence-based regimen that departs from the FDA protocol that’s on the label.” That’s why a district court judge in Oklahoma, looking at the restriction, found that limiting physicians to the label requirements was “so completely at odds with the standard that governs the practice of medicine that it can serve no purpose other than to prevent women from obtaining abortions and to punish and discriminate against those women who do.” In other words, he got it. And then he stopped Oklahoma’s law from going into effect.

The issue in Oklahoma, though, was that the law as drafted was ambiguous. It either had the effect of banning all medication abortions, or—as the state contended—merely provided that medication abortions induced with Mifeprex had to follow the FDA protocol. The Oklahoma Supreme Court decision from 2012, which struck down the law, merely found that the law as written was unconstitutional under Planned Parenthood v. Casey, the 1992 case that reaffirmed Roe but permitted abortion regulations that are “reasonable” and do not impose an “undue burden” on women.

So what happened this week in Oklahoma? Having been told by the Supreme Court to unpack its earlier decision striking down the medication abortion law, the state Supreme Court took 22 pages to explain that yes, in its view, the Oklahoma statute barred physicians from using misoprostol (the second drug in the protocol) and methotrexate (a third drug sometimes used in the abortion-inducing protocol). By focusing on outdated FDA regulations, the state’s intention was to outlaw medication abortion.

Last April, a district court judge in North Dakota struck down a similar ban on off-label uses of abortion inducing drugs. But last year a federal appeals court upheld a related Ohio law, largely on the theory that the restriction was not unconstitutional if a majority of women could still access abortion in some other manner. The split increases the chance that the Supreme Court will have to decide the issue.

Meanwhile, in Texas this week, U.S. District Judge Lee Yeakel upheld a provision of the Texas law that limited doctors to FDA labeling requirements for medication abortions. The Texas law differs from the Oklahoma statute HOW? Judge Yeakel didn’t seem to buy the state’s proffered safety reason for forcing doctors to stick to the labelling requirements: “This court finds that, when performed in accordance with the off-label protocol, medication abortion is a safe and effective procedure, as is medication abortion with the FDA protocol.” He also found that “taken as a whole, the FDA protocol is clearly more burdensome to a woman than the off-label protocol.” But then he deemed the burden insufficient to strike the law down. The restriction wasn’t an unconstitutional ban, he reasoned, since women have other options. And to make sure that women’s health isn’t compromised, he wrote a do-it-yourself health exception into his opinion: “The medication abortion provision may not be enforced against any physician who determines, in appropriate medical judgment, to perform the medication-abortion using off-label protocol for the preservation of the life or health of the mother.”

As a result of this ruling, in Texas, some doctors must prescribe heavier doses of abortion-inducing drugs (unless they see a threat to the health or life of the woman) and can only offer medication abortions up to seven weeks into a pregnancy, as opposed to nine.

How to reconcile the Oklahoma Supreme Court’s decision to strike down the law with the Texas court’s determination that it could stand? Partly the bad drafting in Oklahoma. But it feels like something else is going on.

The Oklahoma Supreme Court struck down the statute by focusing a great deal of attention on the professional imperative requiring that licensed physicians adhere to best practices. Indeed the whole concluding section revolves around the professional obligations of doctors and the Hippocratic oath. The court’s path here is very different path than the one taken by Yeakel, who focused on a woman’s right to medical care (and then said that a woman’s right was not compromised as long as alternative procedures exist). This semi-solicitude for a woman’s health is the result of a years-long campaign by opponents of choice, to suggest that protecting women’s health is so critically important, that every other concern falls away.

If the Oklahoma Supreme Court ruling had been a full-throated discussion of women’s rights, and all the ways regulating medication abortions drastically restrict them, it would have been close to perfect. But the court was thinking about physicians. The Oklahoma Supreme Court’s attention to the rights (and statutory responsibilities) of physicians is reminiscent of Justice Harry Blackmun’s original reasoning in Roe, which as Jeffrey Toobin recently reminded us, had a lot less to do with a woman’s rights than those of her physician. As Toobin wryly observed, the word “physician” appears in Roe 48 times, the word “woman” 44 times. Later cases made clear that the rights of the physician and woman were in fact aligned; that this is the relationship on which the state must not intrude.

It just shouldn’t be the case, 40 years after Roe, that courts still don’t see the rights of women and those of their doctors as equally compelling; that such opinions still just don’t seem to “write” (as the lawyers say). The Oklahoma Supreme Court decision was correct, but it still pinches that the outcome is rooted in the harms to doctors who can’t practice medicine as they see fit, as opposed to the needs of women to get the care they are due. Efforts to legislate first-trimester, constitutionally permissible abortion right out of existence, are subversive and paternalistic. And the cure for legislative paternalism shouldn’t be judicial paternalism.