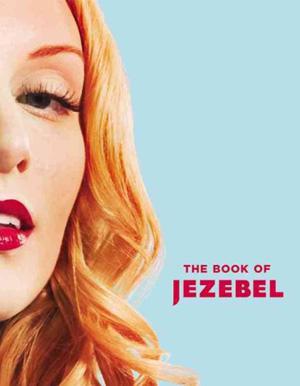

When Gawker Media launched Jezebel in May 2007, it was the first big bid at reimagining popular women’s media for an online audience. Now, Jezebel is going analog. Released today, The Book of Jezebel: An Illustrated Encyclopedia of Lady Things, edited by Jezebel’s founding editor Anna Holmes with contributions from a group of female writers, include Slate contributors Jessica Grose, Amanda Marcotte, and yours truly, is both an earnest celebration of the historical and pop cultural figures that have shaped women’s lives in the 21st century and a compendium of elaborate menstruation jokes. (I wrote many of them.) Critics are divided on how seriously to take the thing: Fresh Air’s Maureen Corrigan found it a “jolly feminist cultural commentary”; the Daily Caller’s Mark Judge counters that “the rage of the Jezebels is indicative of a serious cultural problem that is potentially fatal for the United States.” (Spoiler alert: The cultural problem is daddy issues). I am biased and think it’s great.

I spoke with Anna about translating a blog to a dead-tree medium, the Jezebel definition of cunnilingus, and how to compete with other women without undermining women in general.

Amanda Hess: Now that the book has come out, people keep asking me which entries I wrote, and I honestly do not remember. It’s all a blur of badass historical ladies and uterus jokes at this point.

Anna Holmes: You’ve just described my life.

Hess: The book is a part of a trend in publishing that takes a Web outlet and reimagines it as a print product. As someone who writes primarily on the Internet, I’m of two minds about that: On the one hand, the immediacy and community provided by writing online can be really special, but there’s also a lot of great writing and argumentation that happens online that just quietly disappears. Is that why you’ve turned the website into a book?

Holmes: I don’t know that the trend toward turning Web products into books is that new—we’ve seen peoples Twitter feeds effectively spun into books. But I had some hesitation about doing it with this site, because I don’t think there are many books that have succeeded in translating Web content to print form.

Way, way back when we first started talking about the book, there was some discussion of turning the Best of Jezebel into book form, but I don’t think a book of previously published stuff is that interesting to consumers. But there was something compelling in taking a site that has a known sensibility and translating it into book form in a very explicit way—which is the way we see the world. And when I say “we,” it’s a very broad term, and it should be a broad term—no pun intended. The sensibility of the site has been crafted by the people who have run it, the people who write it, and the commenters and readers as well. There isn’t one party line, except that women should be taken seriously and are awesome and funny—I think everyone can agree on that—and that historically they have not been well-served by women’s media, which is part of why the site started in the first place.

Hess: One of the frustrations of writing in women’s spaces online is that we’re often defining ourselves in opposition to other coverage about women. In my writing on Double X—and in a lot of the writing that appears on Jezebel, too—the pace is so quick that our work is largely a response to an offensive story or the latest frat boy email. Part of the fun of writing the book was to celebrate female culture independently, in a way that’s not bogged down by the day-to-day call and response.

Holmes: A lot of Internet writing is reactionary—I don’t mean that in the revolutionary sense, but that a lot of blogging is about applying readings to things that exist elsewhere in the media. The book is more self-contained. It’s about the situations and concepts that are relevant to being female in the contemporary United States, and not in the granular way that a blog or website demands, which can be very exhausting. Sometimes, you need to explain things more in a blog post to put everything in context—some entries in the book are just a one-liner, because sometimes that’s all that needed to be said. I can’t think of that many posts on the site that were just one-liners. Were you the one who did the entry for cunnilingus?

Hess: I have no idea!

Holmes: It was simply one word, which is: “Mandatory.”

Hess: You left Jezebel three years ago. What advice did you give to the current editor, Jessica Coen, when she took over?

Holmes: I had hired her five months prior, so she had five months to kind of get it. I don’t know I gave her any specific advice when I left—if I did, it was to not spend your every waking hour on the site so that you have no life. I’m a cautionary tale. I went so balls-out that it became an unhealthy thing for me. I didn’t read the site for six months after I left, because I didn’t want to get close to creating a situation where I would meddle. If I saw something I didn’t like, I didn’t want it to come out in some way, if I ran into someone on the street. It was like my baby. I had a baby, and I handed it off to someone else, and now that person is raising that child and I can’t be like, “No! You have to feed her at this time.” Maybe that’s a horrible analogy because I don’t have kids, but it felt like it was such a part of me that I had to just not engage with it.

Hess: Since Jezebel launched, a whole crop of women’s sites—including this one—have emerged that also align pop culture and feminism. That sounds like a great compliment as an editor, but also a challenge. How can sites like Jezebel continue to remain relevant now that there’s more competition in those spaces?

Holmes: When those sites first started popping up, within about a year of Jezebel launching, I remember feeling like, Oh hellllll no. I think I felt threatened, but that very quickly morphed into a feeling of, “I am going to crush you.” I felt competitive, which was not unhealthy, because I was under a lot of pressure—a lot of it self-imposed—that the site be successful. When the competition arrived, I didn’t feel that we were necessarily successful. We were in our infancy. We could have been overshadowed by someone else, and I didn’t want to lose any ground. I felt we had to be not only bigger, but better and faster and insert-adjective-here than the other ones. As time went on and I saw that Jezebel was still growing by leaps and bounds, I felt perhaps less threatened, but no less competitive. After I left the site, I didn’t feel competitive at all and it was easier to see how all of these spaces can coexist. I don’t think there are too many of them. As a genre, it isn’t going anywhere.

On a related point: We as women have been socialized to believe that other women are competition, because we only see so many spaces at the table. We see each other as competition for mates or for professional success. I’ve tried—since I was a teenager and became aware of this in myself—to reject the idea that I need to feel competitive with other women specifically. There’s nothing wrong with feeling competitive with people in general, but when we start to see other women as the enemy, that leads to nowhere good. When people ask me if I feel like the space for women’s websites is crowded, I wonder if anyone would say that about sports websites geared toward men. Are there too many sports websites? The question comes from the idea that there’s a finite amount of space for women to occupy, and I don’t believe that there is.

Hess: As a writer, one of my questions about the proliferation of websites for women is whether they conscribe female writers to women-branded spaces, or whether they can actually extend more opportunities for those writers at legacy publications or more mainstream platforms.

Holmes: Every couple of months someone asks the question. “Why is there such a thing as a women’s website?” Are they somehow ghettoizing or limiting? Men have dominated these conversations for so long, and have been the default point of view on a number of topics for so long, that I don’t see what’s so offensive about a space where females are the default. And there are plenty of men paying attention to the writing on these sites. They’re hungry for it as well. I don’t think that women’s websites are bad for women. I think some types of women’s websites might be bad for women—ones that are overly obsessed with things I reject, like an obsession with heterosexual coupling and finding a man and keeping a man, and all that stuff.* But a lot of these sites have contributed to some really exciting developments in writers’ careers, beyond just talking about women’s issues, because they give female thinkers a platform to showcase their diversity and intelligence and wit. The Internet has leveled the playing field. To get a byline or a great assignment for a high-profile media outlet, you don’t have to have jumped through the same hoops you did when I was young—live in a certain city, work at a magazine, get promoted. That’s been all shot to hell. People still do that, but the quality of writing on the Internet does rise to the top, and does get people noticed—not just at women’s sites but everywhere.

Hess: Another challenge for women finding a space to write online—or in particular, launching their own spaces—is that the pipeline of funding and institutional support is very male-dominated. How can we get men to pay us to start our own media empires?

Holmes: Sucks, right? I don’t know how to tell anybody, male or female, how to fund their own media empire. It’s a question I’m asking myself in the back of my mind every day. I really believe in the Web, and when I start to think about my next step, I know I’d like to have more ownership over the next thing that I do. That would require funding, or a trust fund—which I don’t have. I’m not sure there’s something wrong with having something funded by a man just by definition, but I also don’t know how we find female funders—or how we create more female funders. I’m struggling with that.

Hess: If you figure it out, please let me know.

Holmes: I know, right?

Correction, Oct. 23, 2013: Due to an editing error, this post originally implied that Anna Holmes rejects heterosexual coupling. She rejects an unhealthy preoccupation with heterosexual coupling. (Return to the corrected sentence.)