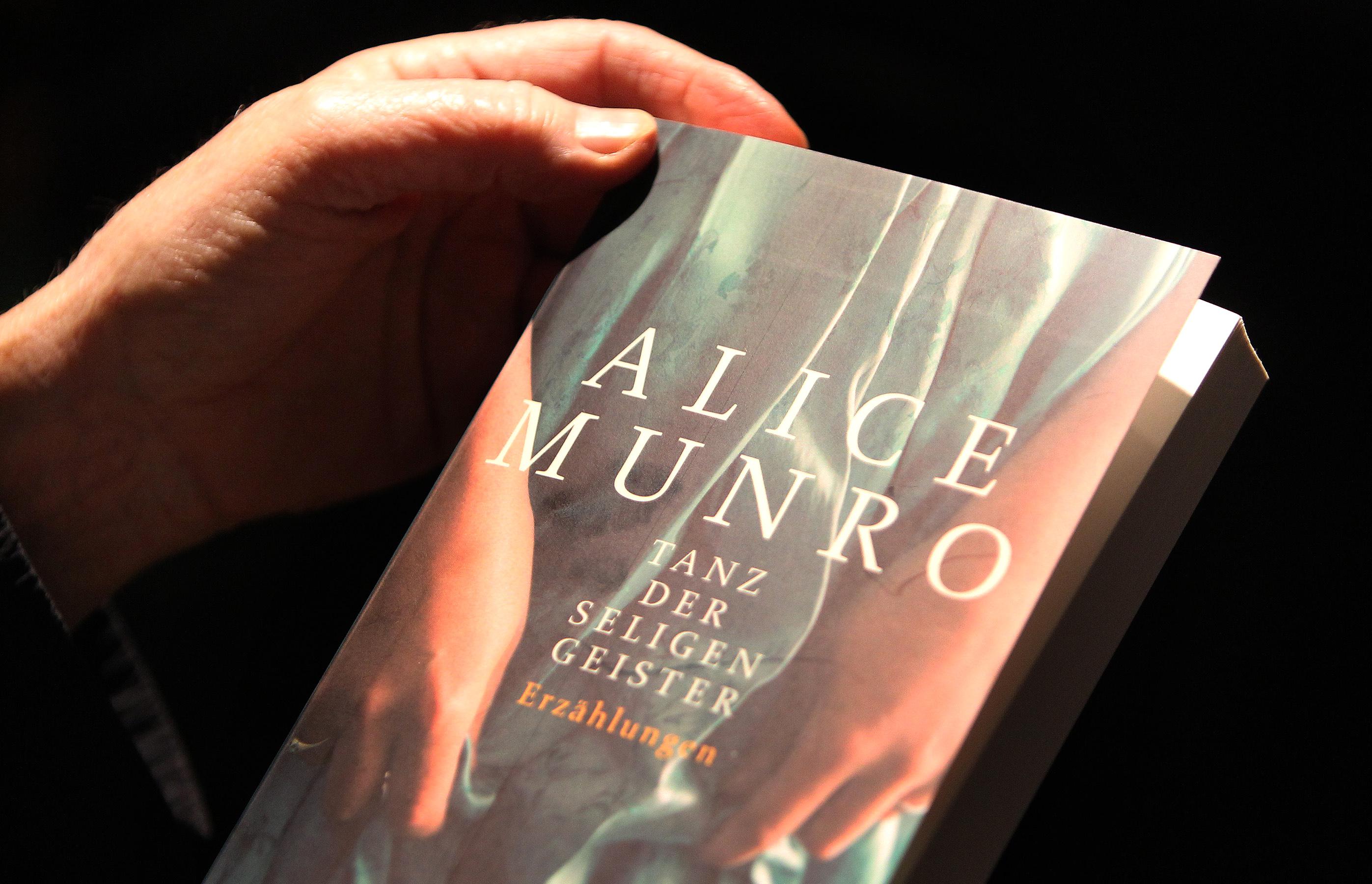

When I woke up this morning to learn that short-story writer Alice Munro had won the Nobel Prize for literature, I felt as happy as a Canadian. Munro is the writer I have loved the most and loved the longest. I never needed a fancy prize to confirm my love, but it felt surprisingly good to get it anyway. (I know I didn’t win anything.)

Munro is only the 13th woman to win the Nobel for literature, and she is a woman who writes— well, I can’t bring myself to say “wrote,” despite her announcement this summer that her recent collection, Dear Life, would be her last. Anyway, she is a woman who writes about women and their concerns: lust, love, security, jealousy, ambition, husbands, aging, housework, boredom, regret, and children. The younger women in her older stories are often poor, or very nearly so; the older women in her later stories are sometimes successful, or married to successful men. She returns so often to the same territory in rural Ontario that her work has been called “Southern Ontario Gothic.” But the fact that she writes about one particular place—and yes, one demographic—belies the diversity of her characters’ personalities and desires: To know one girl in 20th-century rural Ontario is not to know them all.

It’s fair to say she didn’t exactly need the prize, which is why I thought I wouldn’t care if she won. Munro is not a deserving but “difficult” writer like Elfriede Jelinek, or a giant who merits greater renown in the West, like last year’s Chinese winner Mo Yan. Munro has won the Booker, the National Book Critics Circle, the O. Henry, and just about every other award and honor the continent has to offer. When I heard she won $10,000 for something called the “Harbourfront Festival Prize” a few weeks ago, I chuckled to myself, imagining her rolling her eyes and cashing yet another check. Not that she would ever roll her eyes: At 82, she has perfected the “overwhelming favorite acts humbly surprised upon winning” dance. “I knew I was in the running, yes, but I never thought I would win,” she told the Canadian media in a post-Nobel phone interview this morning. Taylor Swift, take notes.

And though the Nobel will certainly boost her book sales and fame, Munro hardly needed more of either. Even before today, it would have been hard to think of a living short-story writer who is more widely read and beloved. Her stories proceed in orderly fashion from The New Yorker to collections that regularly make the best-seller list. When Jonathan Franzen wrote a cover review in the New York Times Book Review of her 2004 collection, Runaway, and framed it as an attempt to correct the fact that “her excellence so dismayingly exceeds her fame,” it would have been easy to dismiss: She was already so famous! But it still felt correct in some way: Alice Munro is so good it’s impossible for her to be overrated. (This is the kind of gushing that inspires occasional backlash. Writing in the London Review of Books in June, critic Christian Lorentzen eviscerated Munro as dull, repetitive, a one-time “epiphany-monger” who now tends to “heap on details for details’ sake and load up her stories with false leads.” Obviously I think he was wrong.)

It’s sometimes considered a kind of gossipy weakness to be interested in an artist’s life apart from her work, but so be it: What we know of Munro’s life makes her work even richer. She was 37 when she published her first collection, and she had to find time to write in the margins of her “real life,” though she seems to have had a way of making those margins wider than most. Here’s how she once described it:

When the kids were little, my time was as soon as they left for school. So I worked very hard in those years. My husband and I owned a bookstore, and even when I was working there, I stayed at home until noon. I was supposed to be doing housework, and I would also do my writing then. Later on, when I wasn’t working everyday in the store, I would write until everybody came home for lunch and then after they went back, probably till about two-thirty, and then I would have a quick cup of coffee and start doing the housework, trying to get it all done before late afternoon.

And before the girls were in school, she worked while her daughters napped, which, as Slate contributor Jessica Grose noted this morning, “inspires one to find the time to be 1% as brilliant.” She has lived a life that seems both full and focused, which can seem an impossible trick.

Later, her professional life presumably got easier. Her stories became well-known, and she enjoyed a long and apparently happy second marriage to a geographer who died this year. They lived together for decades in his childhood home. In her 2006 collection The View From Castle Rock, which featured semi-autobiographical stories drawn from her family history and her own life, she described taking long drives with him, seeking out various plains and glacial moraines in the Canadian countryside. The passage can read as a description of her approach to fiction:

There is always more than just the keen pleasure of identification. There’s the fact of these separate domains, each with its own history and reason, its favorite crops and trees and weeds—oaks and pines, for instance, growing on sand, and cedars and strayed lilacs on limestone—each with its special expression, its pull on the imagination. The fact of these little countries lying snug and unsuspected, like and unlike as siblings can be, in a landscape that’s usually disregarded, or dismissed as drab agricultural counterpane. It’s the fact you cherish.

So I surprised myself by feeling moved this morning to hear about a successful person receiving a fancy prize. Alice Munro didn’t need the Nobel Prize, but she deserved it, and she won. It’s a straightforwardly happy and uncomplicated ending—the kind she never would have gone for in her stories.