It’s been a spectacularly awful week in rape. And that’s not just because of a gang rape of a photojournalist in India. No, it’s also been a really shockingly bad week for American judges dealing with child rape victims, including a Massachusetts woman who has sued to avoid a judicially mandated relationship with her rapist for the next 16 years, and a Montana judge who sent a teacher to jail for only 30 days for the statutory rape of a student who later killed herself.

It is a time-honored legal cliché that hard cases make bad law. That’s a simple way of saying that when courts get bogged down in all the subtleties and complexities of ambiguous human behavior, the legal result isn’t always satisfying. Ariel Levy’s recent exploration of the Steubenville rape case—with its booze-and-football-fueled victimizers and Internet vigilantes—is a pretty good example of all the shades of gray that play out when teen sex crimes are litigated in the courts. But this hasn’t been a bad week in date rape, or in acquaintance rape, or in “he said, she said” rape claims. It’s just been a bad week in rape. In violent, abuse-of-power, unambiguous rape. And what that suggests about where we are heading in the law of sexual assault is worrisome, to say the least.

The first story comes from Massachusetts, where a plaintiff known only as H.T. has sued the commonwealth in federal court for forcing her into a long-term relationship with her rapist. In 2009 H.T. became pregnant as the result of a rape that occurred when she was 14—in middle school. Her rapist, Jamie Melendez, was 20. Melendez pleaded guilty to the rape in 2011 and was sentenced to 16 years of probation. But the conditions of his probation also included an order that he “initiate proceedings in family court and comply with that court’s orders until the child reaches adulthood.” In short, according to the new complaint filed by H.T., the man who raped her was ordered to “initiate proceedings in family court, declare paternity as to the child born of his crime (paternity had already been determined in the criminal case, via DNA testing), and comply with the family court’s orders throughout the probationary period.”

This forced relationship between the victim and her assailant was judicially mandated despite the fact that the “plaintiff and her mother were adamantly opposed to participation in family court proceedings and repeatedly expressed this sentiment to state officials.”

In 2011 the court ordered Melendez to pay $110 per week in child support. Never having seen the child, he sought visitation and then allegedly offered to withdraw his request for visitation in exchange for not having to pay child support. H.T. asked the criminal court judge to order Melendez to pay criminal restitution instead of child support, keeping herself and her child out of his life, but the judge refused. The Supreme Judicial Court for Massachusetts found that she lacked standing to challenge the sentencing judge’s order. So H.T. filed suit arguing that she wants nothing to do with the child’s father, and that she “be liberated from a state court order that not only imposes unlawfully on her liberty for 16 years, but also obligates her with the unwanted and inappropriate responsibility for ensuring Melendez’s compliance with the conditions of his probation.”

Massachusetts is one of 31 states in which rapists are allowed to sue for child custody and visitation. Thirty-one. Last summer, after Rep. Todd Akin’s absurd claims about “legitimate rape,” Shauna Prewitt shared her harrowing story of becoming pregnant after a rape, then dealing with her rapist’s efforts to gain custody of their daughter. In a law review article published in the Georgetown Law Journal in 2010, Prewitt argued for legislation that would protect the estimated 30 percent of women who opt to keep pregnancies that result from rape, noting that in most states, “a man who fathers through rape has the same custody and visitation privileges to that child as does any other father of a child.” As a consequence, a mother will usually bargain away her legal rights in the interest of creating a distance between herself and her attacker. In a legal moment at which we are talking about amending statutory language to say “forcible rape,” it’s worth wondering how it is even possible that we live in a country in which most states privilege the rapist’s right to access his child over the mother’s right to be left alone.

The Montana case is just as appalling. On Monday former teacher Stacey Dean Rambold was sentenced to 30 days in prison for having sex with a troubled 14-year-old student when he was 49. The school district had warned Rambold in 2004 to avoid touching or being alone with female students. In 2008 he entered into a relationship with Cherice Morales, who killed herself two years later, just as her teacher was being charged with felony statutory rape. In Montana a child under 16 cannot consent to sexual intercourse. Period. After Morales’ suicide, Rambold entered a plea agreement in which the case would be dismissed provided he complete a sex-offender treatment program and agree to have no unsupervised contact with children. Prosecutors refiled the charges against him last December after he was terminated from the treatment program for unsupervised visits with family members who were minors.

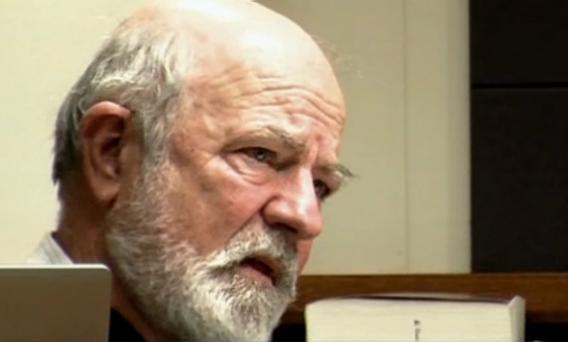

But on Monday, District Judge G. Todd Baugh suspended all but 30 days of what was originally Rambold’s 15-year sentence, explaining in court that Morales was “as much in control of the situation” as her teacher was, and that she was “older than her chronological age.” Which is actually impossible. At Monday’s hearing Rambold’s lawyers argued that he has suffered enough, losing his career and his marriage, and has the “scarlet letter of the Internet” due to the publicity around the case. As Judge Baugh explained, “I think that people have in mind that this was some violent, forcible, horrible rape. It was horrible enough as it is, just given her age, but it wasn’t this forcible beat-up rape.”

In the days since that sentence was announced, Judge Baugh—who is running for re-election in Billings—has faced angry blowback, including a petition for his removal from the bench, and he has since published an apology in the Billings Gazette, in which he observed that his comments had been “demeaning of all women” and that “I am not sure just what I was attempting to say, but it did not come out correct.” He defended the sentence, however, explaining that Rambold’s violations of the rules of his treatment program were not serious enough to warrant the reinstatement of significant prison time.

Please don’t tell me that this is all a result of Miley Cyrus and hypersexualized teenagers and ambiguous legal lines and feminist lynch mobs. We have strict liability for having sex with minors for a reason, and claims that the young temptresses of today are somehow sowing confusion in their male victims-slash-assailants predate Lolita. These are grown men having sex with children who cannot legally consent, with one case ending in a pregnancy and the other ending in a suicide. And these are judges who find ways to empathize with the accused and to shift blame and consequences onto the victims. There aren’t supposed to be balancing tests in statutory rape cases, and as admirable as judicial efforts to reunify “families” and sympathize with the shattered lives of rapists are, the notion that rape is still not a serious crime is sufficiently horrifying when it appears throughout the media or the mouths of the accused. That it is coloring how judges view underage female victims and their assailants is an astounding testament to all the upside-down ways we think about rape. Shifting the burden is an old, old game. The law is not supposed to allow it.

According to a survey published by the Centers for Disease Control in 2011, nearly one in five American women have been raped or experienced attempted rape. Someone is sexually assaulted every two minutes in the U.S., and most (54 percent) sexual assaults are never reported to the police. Yet somehow it’s still fashionable in some circles to claim that rape law is too draconian, that violence against women is a cunning feminist conspiracy, and that the legal system needs to course-correct for all the ways it’s too tough on men. If ever there were cases to bolster those arguments, these are not the ones. And when it’s the easy cases that start to make bad law, it’s really time to worry.