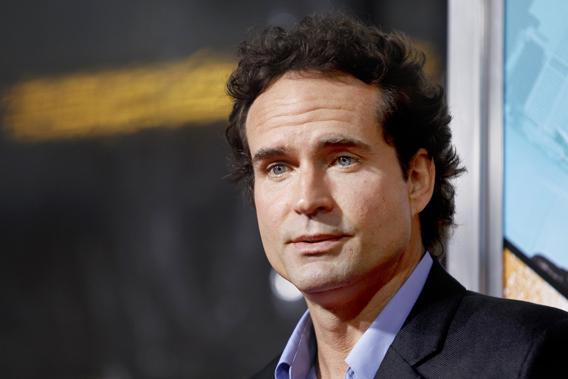

The actor Jason Patric wants to be a dad. The mother of his biological child, 3-year-old Gus, wants him to just be a sperm donor. Who wins?

If I taught family law, I’d make this case my last class of the semester, because it’s right at the edge of a frontier of parenthood that courts and states haven’t settled yet. It also scrambles the usual assumptions. Traditionally, it is fathers who have run from parental responsibilities and mothers who have tried to hold them accountable, often to win child support. I’m not talking about most fathers, of course, just the ones who essentially say they got tricked—they just gave sperm, or they just had sex, and didn’t intend to become fathers at all.

In this case, Patric wants a relationship with his biological son, and it’s Gus’ mother, Danielle Schreiber, who is asking the courts to turn him away. It’s a different entry point into an old fight. But Schreiber’s stance shouldn’t change the underlying rule: Unless both biological parents agree before birth that the father has no rights at all, courts should presume that he is indeed the father, not just some guy who ejaculated into a cup.

Patric and his ex-girlfriend, Schreiber, conceived Gus via in vitro fertilization. Patric says he spent time with Gus after the boy was born, until Schreiber cut him out. He has pictures to prove it. “I want my son back,” he told Katie Couric. He says he was there from the start and signed a document stating that he was Gus’ “intended parent.” Schreiber say that Gus was conceived after she and Patric broke up, and that neither of them intended him to be the boy’s father. “It’s not about him having a relationship or contact with Gus. This is just about rights,” she said, also on TV. “Me preserving my right to be a sole legal parent, not having to share that with someone who has never intended to and never raised Gus.”

So far, Patric is losing. A California court ruled that he has no parental rights. The judge interpreted state law to provide that if a man isn’t married to the mother of his biological child, and gives her his sperm, then the general rule is that he has no paternity rights. It doesn’t matter whether he spent time with the baby afterward—or what might be best for the child.

If you think about it, that’s pretty shocking. Usually, family law presumes that two parents are better than one, University of Florida law professor Lee-Ford Tritt pointed out when I called him to talk about this case. That way, a child has two sources of love and income. The two-parent rule doesn’t apply to anonymous sperm donors—no one would donate if it did. Also, if the sperm donor is someone the mother knows, the parents should be able to contract away his parental rights if that’s what they want. Otherwise, it will be harder for women to go to men they know for sperm, and that’s not a good outcome. Sometimes children are better off knowing who their fathers are, even if the fathers aren’t legally responsible for them. The law should allow for different kinds of donors and family constellations.

But if there’s no clear agreement between the parents, then the law should go back to presuming that the genetic father should be treated as the real father. The judge who ruled against Patric did the opposite. He’s saying, in effect, that Schreiber gets to decide to bar Patric from any kind of parental involvement. We’re not talking about whether Patric gets to raise Gus—that’s a separate custody issue—just about whether he has any leg to stand on in court proceedings about Gus at all. Why should this decision about Gus’ parenthood be up to his mother alone, without any consideration of how Patric behaved toward Gus, and whether Gus would be better off with Patric in his life?

Courts should, and often do, ask a different question: Has the father “held out” a child as his own? That’s the legal term of art for a test that looks at the father’s relationship to the child. Did Patric spend time with Gus or pay for any of his care? Did he acknowledge him as his son? “Holding out a child as one’s own is huge in the courts for determining parental rights,” Tritt says.

That’s not how current California law works, however. It provides that a sperm donor, to a bank or for IVF involving a woman other than his wife, “is treated in law as if he were not the natural father of a child thereby conceived, unless otherwise agreed to in a writing signed by the donor and the woman prior to the conception of the child.”

Patric is trying to change that. He has convinced the state legislator who wrote the 2011 law defining what it means to be a sperm donor to propose an amendment. The new bill would allow a sperm-donor father or a mother (actually “any interested party”) to go to court “for the purpose of determining the parentage of a man presumed to be the father because he receives the child into his home and openly holds out the child as his natural child.”

David Plotz, author of The Genius Factory: The Curious History of the Nobel Prize Sperm Bank as well as the editor of Slate, would go further. He argued to me in an email that any genetic father who doesn’t explicitly renounce paternal rights in advance, or donate sperm to a bank anonymously, “should be presumed to have paternal rights, unless he acts in a willfully and legally approved manner to abandon those rights. A known donor who is a friend enlisted to donate should have to go through a legal process to separate.” That way, the law guards against “casual decision making about a huge life choice.”

I like that point. The clash between Schreiber and Patric shows how hard it can be to settle questions of parenthood after the fact. The best role the law can play is to push parents to figure out who is who in a child’s life at the outset. And when they don’t, courts should probably stick with the old presumption that two parents are better for a child than one. A mother, or a father, should have the chance to prove that presumption wrong. But that’s the place to start.