In August 2008, Amanda Lindhout was a Canadian waitress in her late 20s who saved up her tips for bursts of ambitious travel. She’d backpacked through dozens of countries, including hot spots like Pakistan and Afghanistan, and she’d become a budding journalist. To give her career a boost, she finagled an assignment in the hottest spot of them all: Somalia. “I understood that it was a hostile, dangerous place and few reporters dared go there,” she writes in her new book due out next week, A House in the Sky. “The truth was, I was glad for the lack of competition. I figured I could make a short visit and report from the edges of disaster. I’d do stories that mattered, that moved people.”

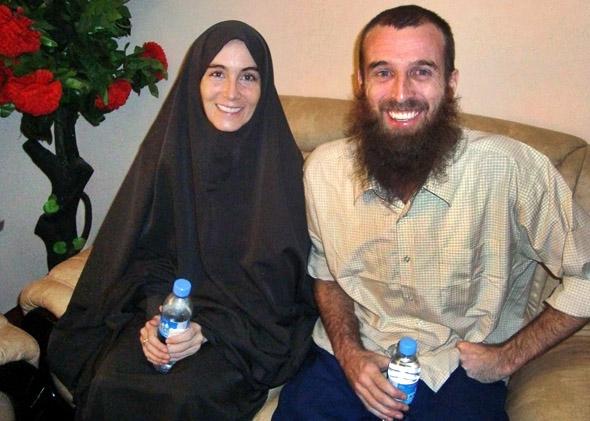

Lindhout has written such a story, though nothing else about her Somalia journey went according to plan. On her fourth day in the country, en route to report on a hospital and health education program for women outside Mogadishu, Lindhout was kidnapped, along with Nigel Brennan, the photojournalist (and former boyfriend) she was traveling with. She spent the next 460 days in a hell of captivity. What’s amazing about Lindhout’s book, which she wrote with New York Times Magazine writer Sara Corbett, is the clarity of her memory and the thread of hope that she somehow holds on to. Lindhout manages to tell her story and to transcend it. Her account stands as a nonfiction companion to Emma Donoghue’s shattering, haunting novel about captivity, Room.

When I finished A House in the Sky, I wanted to know even more, so I called Lindhout and Corbett to ask the questions the book raised for me. An edited and condensed version of our conversation follows.

Slate: How did you decide to write this book, and then go about doing it? Tell me about the process.

Amanda Lindhout: I knew what I didn’t want to do. I didn’t want to write a typical captivity narrative, beginning and ending with only that snapshot in time. That seemed to be what most publishers were interested in. But Sara and I had a mutual friend, Robert Draper, another writer who was in Somalia when I was, and appears briefly in the book. After my release, he connected us. For me, it was instantaneous when we met, because Sara, like me, saw the story as a much bigger one. We agreed that it should encompass my years of travel around the world and my childhood. We’ve said since we started that we see the world as a character in the book. There’s a lot of adventure and even fun in the first 100 pages. Yes, the captivity is often very brutal, but as a reader you also go on a larger journey with me as this young woman. It’s more honest and real that way, and to understand why I was in Somalia, it’s important to understand who I was at that point in my life.

Slate: The most riveting scene in the book is your escape attempt, excerpted here. You and Nigel managed to pry open a bathroom window and run into a nearby mosque. Dozens of men surround you. One of your kidnappers fires his gun, parting the crowd. One Somali woman steps forward and calls you her sister. Your kidnapper starts trying to drag you out of the mosque. “I don’t remember any of the onlookers trying to stop him,” you write. “It was only the woman who tried.” What do you want readers to take from this scene?

Lindhout: As you probably know, I also run a nonprofit organization that I started after my release, the Global Enrichment Foundation. We work a lot with Somalian women. What I want readers to understand about the woman in the mosque is connected to the work I do now. Women in Somalia face almost unimaginable oppression. Most basic freedoms are denied them in many parts of country. And yet they can be so courageous. The woman in the mosque that day risked everything, risked her very life, to help another person. It was instinctual, I think, but also, there is a confidence and power in what she did. I see that, too, with the women we work with in Somalia, in their desire to have an education, even when that puts their life at risk, in communities in which females are not supposed to go to school. There really is a thread of hope in that country, and it lies with the women.

In the year we launched, 2010, we offered 10 scholarships for women to go to university. We got 6,000 applications for 10 scholarships. Many came from places where women are forbidden to leave their homes without a male escort, much less go to school. Most women didn’t have the education to actually go to university, but all those applications spoke to their desire nonetheless.

Slate: Reading that scene, I struggled with the idea that so many other people in the mosque that day knew you were being held against your will, but did nothing.

Lindhout: The conclusion I’ve come to about that is that people in a country like Somalia understand how little value is placed on human life in a way that you can’t comprehend, and even I can’t. That day, they had to protect own skin and own family. It’s about self-preservation more than a lack of caring. The people there were scared to get involved, and I can understand that. It what makes what the one woman did all the more remarkable.

Slate: Knowing what you went through, I find it incredible that you have returned to Somalia and that your work is focused there. When you started your foundation, did anyone say, How can you want to do this? How can you go back there?

Lindhout: When I came home, I didn’t feel I wanted to go back to Somalia ever. But I did think in captivity that if I made it out, I wanted to do something, in whatever humble way, to contribute to positive change in the country. I understand more than most outsiders what’s going on there, and that came with a feeling of responsibility.

But yeah, a lot of people didn’t understand why I’d want to have anything to do with that country. That played into another aspect of my homecoming. During my reintegration, often I couldn’t connect with my friends, or other people in my life, because I came back fundamentally a different person.

Slate: Can you tell me a bit about your recovery? It must be an incredible struggle.

Lindhout: Thank you for that, because yes, it is. I think I’ll be healing from the kidnapping for the rest of my life. Now, four years later, I have many, many really good days. But it’s also still hard. I work with a wonderful psychologist sometime every day. And I’m committed to be well. I hope that one day it will be easier, [that my experience] will be processed at a deeper level, and the memories and the symptoms of PTSD won’t be as intense and often as they are now.

Slate: Are there ingredients for resilience?

Lindhout: There’s no one recipe. For me, it’s about facing the fears that are deeply ingrained. I’m faced with a crossroads every day. I’m afraid of the dark, but I choose to sleep in the dark. I can fall right to sleep with the lights on. But I want to be someone who can sleep in the dark, so that’s the choice that I make. I’m afraid of elevators, because they are an enclosed space, but I get in. Getting on a plane is hard for me, but I do it, because travel is vital to me.

Slate: So you’ve continued to travel?

Lindhout: Yes, I’ve done a number of fun, adventurous trips. I went hiking in Amazon and on the Tibetan Plateau in India. I travel differently now than I did when I was in my mid-20s. I take safety precautions I didn’t before—I take out ransom and kidnapping insurance, for one thing. And I’m going to countries that are not as dangerous.

Slate: Do you travel alone?

Lindhout: I do a lot of travel by myself. Especially during this period, when I’m processing a lot, not only the 460 days in Somalia but the whirlwind that has been my life on the other side, where so much has changed. Time to reflect on all of that, when I travel, helps me.

Slate: How have you raised the money for your foundation? It’s pretty amazing that you started a whole new organization.

Lindhout: We’ve raised more than $2 million. I started with me talking, at schools and other places, about what I wanted to do next. And people would give. The funds really started coming in 2011, because that was the year of the devastating famine in Somalia. We fundraised for a hunger relief organization, Convoy of Hope, and the Today show did a nice story. The CEO of Chobani Yogurt saw it and reached out. They’ve given us $1.2 million since then. The rest of the money comes from individuals. We have small offices in Ottawa, Nairobi, and Mogadishu. I take no salary—I never have.

Slate: You mentioned that you’ve had trouble reconnecting with some of your friends. What about your family? Your parents play such an important role in the book, and in getting you back.

Lindhout: In my immediate family, we are all much more close than we were before. That’s a really good thing that came out of my kidnapping. I’m closer to my brothers, my mom, my dad, and my dad’s partner. We have remembered through my experience the importance of family and how much we love each other. We’re still living that four years later—it hasn’t dissipated.

Sara Corbett: Amanda and her mom live on the same block.

Lindhout: I’m at her house right now! We have meals together and see each other a lot and we can take care of each other.

Slate: I’m impressed that she lets you out of her sight.

Lindhout: My mom is amazing. She not only lets me out of her sight, she understands that being out in the world is vital to who I am and she seems to have no animosity or anger for the choices I continue to make to travel.

Slate: Your parents paid the kidnappers ransom for your release. In the book you talk about your guilt about that. Have you paid them back?

Lindhout: Literally, yes. My dad had remortgaged his house to the last penny. I have paid him back. I did. As far as my family getting on our feet again, many people in the communities where we live wanted to see us succeed. That giving is completely separate from the foundation.

As far as my guilt goes, I’ll probably live with that for the rest of my life, too. It’s not just the monetary loss, it’s what my family lived through because of my choice to go into Somalia. But I don’t want to live my life attacking myself for that decision day in and day out. I make the choice every single day to forgive myself for it. I don’t always get to that place, but I try.

Slate: There is a small but wrenching moment in the book when you mourn the loss of your plucked eyebrows. You know it’s a minor vanity, but I could completely understand the feeling that your body was no longer your own. You also describe having fungus on your face, broken teeth, and illnesses. Are you OK now, physically? Your author photo is lovely, but I want to make sure!

Lindhout: The fungus went away really quickly when I had the proper creams to put on it. A couple of weeks after my release, I was beginning to look like Amanda again. My eyebrows were plucked in the hospital—I took care of that. And my teeth have been repaired. But there is also serious damage. I was really, really sick, physically and emotionally, and I’m still physically recovering. Particularly my digestive system. The experience of starvation essentially changes you: Your intestines stop producing the good bacteria that breaks down food. A lot of things still make me sick to eat, and there are still long periods when it’s hard to eat anything.

Slate: Tell me if I’m being too nosy, but I finished the book wondering whether you would want to be in a romantic relationship, and, with apologies for being presumptuous, wanting that for you. What’s your thinking about that?

Lindhout: It’s not part of my life now, but it’s something I really look forward to having in my future. The last few years, I’ve been focused on taking care of myself and my recovery. At some point in the future, I do feel excited for that.

Slate: How old are you now?

Lindhout: I’m 32.

Corbett: You’re young!

Lindhout: That’s what Sara is always saying—that I have plenty of time.