William Faulkner, in his acceptance speech for the Nobel Prize, declared that the only subject worth writing about is “the human heart in conflict with itself.” Great writing demands the universal truths of “love and honor and pity and pride and compassion,” says Faulkner; any writing without pity or compassion is “ephemeral and doomed.” As Kafka wrote in a letter to his friend Oskar Pollack in 1904, “A book must be the axe for the frozen sea inside us.” It’s compassion that shatters the ice.

But somehow we no longer require compassion from the literature we admire. We admire writers who celebrate irony, disdain, contempt, who establish emotional distance rather than intimacy. We’ve come to confuse compassion with sentimentality and we’re slightly embarrassed by both. Have people changed, in some fundamental way? Is the human heart no longer in conflict with itself? Is this deep inner conflict no longer important?

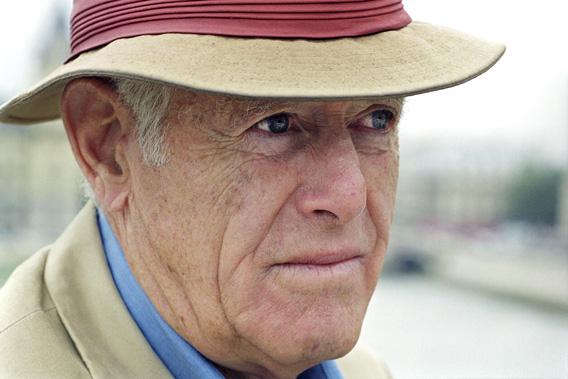

James Salter is praised as a writer’s writer, with good reason: His work is hauntingly beautiful. Each word seems inevitable and perfect, as though the sentences were carved in marble. His voice creates an enchanted forest, and we move, entranced, through its deep shadowy glades. The spell is such that we might not notice the content. If we did, we’d pause, in confusion and dismay.

Salter’s latest book, All That Is, is written in the episodic style of a memoir. It recounts in a meandering fashion the story of Philip Bowman, who grows up in a modest fatherless household in New Jersey and goes into the Navy in World War II, where he sees action in the Pacific. He comes home and goes to Harvard, where he feels like an outsider. He finds a job in publishing, which becomes his career. He gets married, then divorced. He has affairs, he moves house. In the end he meets another woman.

Bowman, like most young men, thinks constantly about sex, and sees women almost solely in physical terms. The jokes and comments made by him and his friends are coarsely sexist. Perhaps we’re expected to forgive this, because sexism was then common. But this isn’t Faulkner, using the N-word while it was still current. This is Salter, in 2013, writing racist and sexist fantasies—like the one about the black maid who is laid down naked on her belly so her white boss can set silver dollars on her back before he screws her. Salter writes this passage with loving attentiveness, infusing it with a hushed and secretive heat. He compares it to “certain feverish visions of saints.” Apparently we’re meant to think of this like a kind of religious ecstasy—but isn’t it kind of loathsome?

About halfway through, Bowman (Beau-Man, or the Archer—he is prodigiously handsome, and prodigiously good in bed) falls in love with Catherine and they have great sex. She finds him a beautiful house in the Hamptons. He won’t marry her, but he buys the house in both their names. She lives there with her teenage daughter, Anet, while Bowman comes out on weekends. Catherine betrays him, sues for sole possession of the house, and wins. Enraged, Bowman leaves the Hamptons. Several years later, when he’s around 50, he runs into Anet, who is around 20. This is his chance, and he mounts a calculated campaign. He seduces her, introduces her to hashish, and then takes her on a romantic trip to Paris. They have great sex, during which she lovingly surrenders herself, making it “plain she was his.” That’s what he wanted, and while she’s asleep he walks out, leaving her without money or a ticket home. It’s quite a remarkable act of cruelty: revenge carried out on an innocent, and driven not by a great emotion like love or grief or even rage, but by small, dishonorable ones—vindictiveness, hoarded spite, pure malice.

The icy heart is not new for Salter. His earlier novel, A Sport and a Pastime, is also marked by emotional detachment, and the title story of his last collection, Last Night, is remarkable for its inhumanity. A woman dying of cancer spends a final evening with her husband and a friend. They spend a last, elegiac dinner together, drinking a splendid wine. At bedtime the husband and wife retire upstairs where he injects her with a lethal dose of morphine. Then the husband retires downstairs to spend the night with his girlfriend—the close friend who came to dinner. They have great sex. But the morphine doesn’t work, and to everyone’s dismay, the wife survives. Sadly, the wife’s discovery of the erotic liaison between the other two is the cause of their breakup, though the husband does his best to sustain it.

Bowman feels entitled to his vindictiveness: He has no scruples and feels no remorse, and nothing in Salter’s prose suggests he should feel otherwise. There is no conflict within this human heart, and herein lies the book’s great flaw. Salter presents Bowman as a kind of prince, a man we’re intended to admire. He’s a man of sensitivity and refinement, who loves good books, good shirts, good wine and women, though his love for women is almost entirely sexual, and his deepest engagement with them occurs in bed. He is at moments candid about his inability to empathize, but Salter presents this not as a flaw so much as the natural entitlement of man. When Bowman’s wife refuses him in bed, “He knew he should try to understand but felt only anger. It was unloving of him, he knew, but he could not help it.”

Katie Roiphe, writing in Slate, characterizes the book as a brilliant indictment of love—but love is an abstract emotion, you can’t indict it. In fact what Salter does is reveal his own incapacity for that huge and engulfing passion. As Roiphe says, he writes “as if he is watching life down here from a very distant planet. … There’s a disturbing anonymity to Bowman’s attachments. … Salter seems to be saying that these unique, individual ardent attachments could just as easily be with another woman encountered on a different day.” Bowman is an emotional isolate and a narcissist: Musing on the end of an affair, he thinks sentimentally of himself: “They had done things together that would make her look back one day and see that he was the one who truly mattered.” Cold and withholding, Bowman’s character denies the deepest and most fundamental aspects of compassion. A protagonist whose view is narrow and fixed means an absence of struggle and complexity; as an authorial vision, Salter’s is limiting and constrictive.

Bowman’s actions reveal that he’s not the noble prince. He’s Iago, ruthless, mean, and vengeful. Shakespeare knew, of course, that you can’t make Iago the main character—he isn’t large enough. He has only one point of view: his own. A villain—a character without morals or compassion—doesn’t offer enough substance or complexity for a great protagonist, just as its opposite does not—a Pollyanna, someone without capacity for hatred, rage, or envy.

Certainly there are loathsome creatures in celebrated works of fiction—Humbert Humbert is a prime example. But I’d argue that Lolita fails to reach greatness for this very reason—there is no conflict within this human heart. Humbert’s icy coldness, his monumental disdain for every character he meets, turns him into a parody of a human being, and the book itself is a parody of a romance. Its brilliant writing and shocking content have mesmerized and titillated readers, but the book won’t endure beside King Lear. Lacking compassion, interior conflict, and consequences, Nabokov’s vision devalues human experience, instead of celebrating it.

Why do we read great fiction? For many reasons, and one of them is the beauty of the prose. For that we read Salter: His grave and sonorous descriptions, of landscape, of weather and of sex, are almost unmatched. But another reason we read it is to expand our understanding of the human heart, and for that we need someone who offers an expansive vision, someone who understands the human heart in all its spaciousness and reach. Salter doesn’t seem to be such a writer; he doesn’t seem to understand the vastness and the heat of the deep interior spaces. He moves only through the cold outer chambers, and, though beautifully observed, this is bleak territory, and what is written there is only half the truth.