It has become a truism that “men don’t read women.” The assertion is taken as self-evident by feminist publications like Salon (“while women read books written by men, men do not tend to reciprocate”) and shown anecdotally by blogs. It is also perpetuated by male bastions like Esquire, which recently released a list “of the greatest works of literature ever published” featuring one (1) book by a woman out of a total of 75. (Dudes like stuff that is “plot-driven and exciting, where one thing happens after another,” helpfully explains Esquire’s editor-in-chief, who introduced Fiction for Men e-books to widespread scorn last year.)

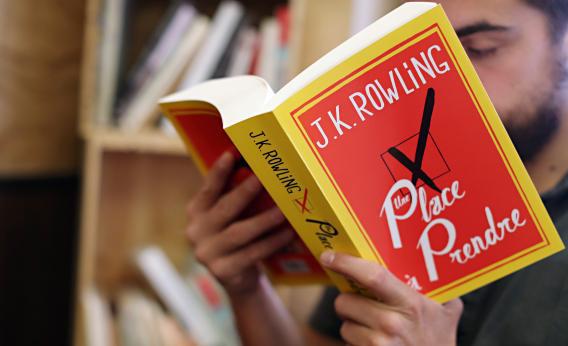

To be sure, the inequalities of the literary world are as plain as the nose on Jonathan Franzen’s face, and many writers and readers alike remain outraged about this unbalanced state of affairs. The Women In Literary Arts numbers for 2012 (compiled annually by VIDA) have barely budged from 2010 and 2011—men still dominate the major outlets as tastemakers, reviewers, and authors whose works are deemed worthy of review. The Nation recently published a cri de coeur by novelist Deborah Copaken Kagan lamenting “centuries of literary sexism, exclusion, cultural bias, invisibility. There’s a reason J. K. Rowling’s publishers demanded that she use initials instead of “Joanne”: It’s the same reason Mary Anne Evans used the pen name George Eliot.” And a recent Salon interview with Meg Wolitzer addressing these frustrations is titled “Men won’t read books about women.”

The truth is more complicated. Of course men read books about women and have for centuries—what are Madame Bovary and Anna Karenina if not classic books about women? Those canonical examples are merely a couple of the ones explicitly named for their central character. Nobody picking up those lauded works of fiction could claim to have been misled by the title to think they were reading about Hitler’s Germany, or fishing, or fishing in Hitler’s Germany, or whatever else men are solely supposed to want to read about. (Tell me, Esquire!)

OK, you say, but those are books about ladies and traditionally feminine spheres by men. True enough! The same can be said for contemporary publishing phenomena like The Girl With the Dragon Tattoo, The Golden Compass, and their sequels. Let us restate the argument, then: Perhaps men don’t read books by women. That is a solid thesis, but it’s based more on self-perpetuating impressions and assumptions than facts. Because publishers, editors, and agents fear that men won’t read books by women, they encourage people like Rowling and Evans—and, for that matter, the Bronte sisters, Hilda Doolittle, Ethel Florence Lindesay Richardson, Karen Blixen, Alice Sheldon, Amandine Lucie Aurore Dupin, and an exhausting number of others—to hide behind gender-obscuring initials or pen names, and thus they exacerbate the problem. A male-seeming author of a well-loved book doesn’t help to change the perceptions of a male reader, just as a child who hates spinach doesn’t come to love it when it is blended skillfully into his cupcake.

Currently, the No. 1 best-selling book on Amazon.com is Sheryl Sandberg’s Lean In. Also making up half of the top 20: Susan Cain, E. L. James, Sarah Young, Kate Atkinson, Gillian Flynn, Gwyneth Paltrow, Haylie Pomroy, Mimi Spencer, and F. Scott Fitzgerald, for his masterpiece about love, loss, romantic longing, and the hottest parties in town. In 2012, again, 10 of Amazon’s top 20 best-selling books were written or co-written by women, including Nos. 1, 2, and 3. In 2011, the total was six out of 20, and in 2010, it was eight, but numerous spots both years were occupied by the tales of Stieg Larsson’s female vengeance demon Lisbeth Salander.* Agatha Christie wrote one of the best-selling books of all time (though she gave it a truly heinous title). Margaret Mitchell wrote another, and she shares that honor with Harper Lee, Anne Frank, Anna Sewell, and Johanna Spyri; J. K. Rowling wrote several, as did E. L. James, James’s hero Stephenie Meyer, and the much more sedate L. M. Montgomery. Perhaps a voracious female audience is enough to shoot “mommy porn” like Fifty Shades of Grey and Mormon porn like Twilight to the top of the charts, but it can’t alone account for the tremendous international appeal of by-women-about-women sensations like Suzanne Collins’ The Hunger Games trilogy or Gillian Flynn’s Gone Girl. These are not anomalies; this is progress.

It seems clear, then, that men do read books by women and they do read books about women. Occasionally they read books by women, about women, and even esteem them, as in the case of Virginia Woolf’s To the Lighthouse, Elizabeth Strout’s Olive Kitteridge, and Toni Morrison’s Beloved, which was voted the best novel of the past 25 years in the New York Times (it perches atop a list otherwise embarrassingly short on women). Hilary Mantel, Zadie Smith, Jennifer Egan, Marilynne Robinson, Tana French, Ann Patchett, and Cheryl Strayed are only some of the other prize-winning women writing under their own names, who are not only at the top of their game but at the top of their field.

Female authors still have a long way to go before they achieve parity with their male counterparts. The establishment, which as a whole has mainly pretended to take them seriously for the last 30 or so years, is still biased against them—often unintentionally or thoughtlessly. This bias seems to arise less out of malice than out of habit, because men’s experiences are assumed to be universal in a way that women’s aren’t and because men have been writing, publishing, and reading their own stories for almost a thousand years with almost no competition.

Holding the establishment to account for its oversights and entrenched prejudices is key, and it benefits all of us that a range of public intellectuals, from the brilliant Roxane Gay to the tireless soldiers of VIDA, continues that depressing work. But merely repeating the simplistic myth that men don’t read women discourages women and other underrepresented groups from following Amazon’s No. 1 best-selling author Sheryl Sandberg’s advice. It further codifies the noxious idea that men are intellectually uninterested in women as the Way It Is and the Way It Has To Be, because it’s the Way It Always Was. And it obscures the positive change happening, albeit slowly, in the literary world.

Correction, April 25, 2013: This post originally mispelled Gwyneth Paltrow’s first name and Stieg Larsson’s last name. (Return to the corrected sentences.)