Life is fragile, use it roughly. Wrest from it all you can. Love in it what you’ve got. For once it begins to end, the greens in your fridge will rot less quickly than you do.

I know because it’s just happened to my dad.

On Jan. 1, my father announced with some pride that he was the only one in our small family who’d made it through the holidays without getting sick. On Jan. 2, he awoke with a fever. On Jan. 3, he was dead.

By the time the coroner sent his body back to the mortuary two weeks later, it was so severely decomposed that the funeral directors beseeched my mother and me not to see it. We were just beginning to sort through vegetables he had bought to make my little girl fresh juice that day. Most of them were still good.

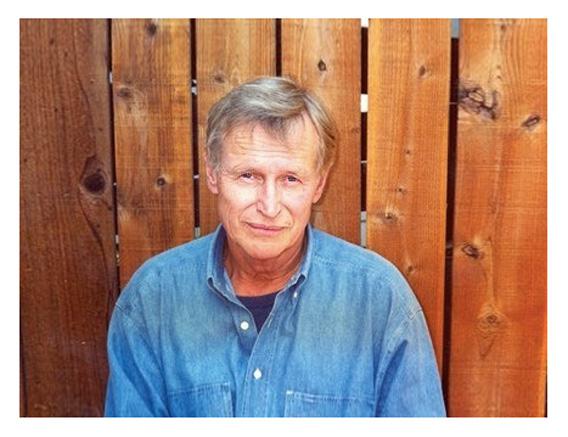

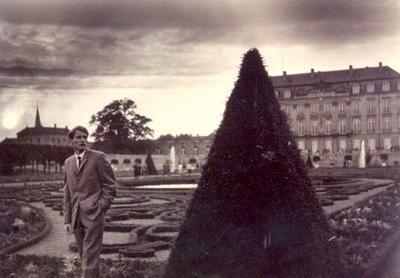

Wolfgang Nehring was a scholar and a gentleman, a stoic and a romantic, a handsome devil who kidnapped the woman he loved out of the home of her boyfriend in 1964 and married her immediately thereafter. He was an impassioned lover of German literature; a powerful hiker, swimmer, and prose stylist; an idealistic and demanding university professor; and—surely to his shock—an unparalleled grandfather to his exceptional little grandchild, Eurydice.

When Eurydice contracted acute leukemia at age 1, my dad searched high and low for medical advice and visited her in the hospital every day for seven months until she healed. His own hospital experience was less successful: After being wheeled into the emergency room by his general doctor in response to sudden back pain that left him unable to walk, a high fever, vomiting, and a loss of balance, he was sent home without any treatment and died within four hours.

Had this swiftest of exits occurred 20 years down the line, it might, in fact, have been graceful. But my dad stood at the brink of a new life when he was felled by a 20-hour infection and failed by the medical profession. His body was in the best shape it had been in 20 years—100 percent cancer-free, as the coroner intoned to me on the phone: Every organ was apparently healthy. (It is only, ironically, a coroner who can give you so clean a bill of health: No other doctor can conduct as thorough an examination without putting the patient at high risk.) Moreover, his horizons were widening, his imagination deepening, and his spirit filling with a fresh kind of love.

Death, it turns out, does not respect our plans for personal improvement. It does not rank us as human beings or decide who’s deserving of its favors and who isn’t.

Often it repulses those who flirt with it daily and who long—half or whole-heartedly—for its embrace. Often it rapes those who ignore it or spend years engaging its enemy, life. We must get away from the idea that there is justice. We must get away from the idea that the universe is benevolent—either to the good or to the “healthy.” The only person to whom the universe is benevolent is the person who squeezes all life into a chestnut in his palm and squeezes its juice—the one who grabs quality regardless of quantity.

In the Italian and English Renaissance, this was a cliché: “Carpe diem,” they called it, “Seize the day for tomorrow you shall die.” Princes and poets alike used it to get their heartthrobs to sleep with them more quickly: “The grave’s a fine and private place, but none, I think, do there, embrace,” coaxed the 17th-century lyricist Andrew Marvell. But the transience of our lives is not just an argument for lovemaking. It is an argument for loving. An argument for loving children. Experiences. Tragedies. Destinies we may not have thought intended for us, but which we can make our glory. My dad, when he died, was still director of graduate studies in UCLA’s German Department, but he had begun to plan a new existence in Berlin or Paris, a life of philosophical writing—the Montaigne chapter of his career. His relationship with my mother was the most tender and gentlemanly I recall seeing it. His relationship to my daughter was a thing of resplendent beauty.

My dad did not especially want to be a granddad. He was not one of those parents who needle their kid to have kids—quite the reverse. When, under difficult circumstances, I was expecting the birth of Eurydice, my dad had one word of advice for me. “Let me give you one word of advice,” he said. I perked up my ears: It was not so often he proffered advice to me. “Don’t send baby pictures. People hate baby pictures. Keep baby pictures to yourself.”

I was a bit crestfallen at the time.

Cut to December 2012. My father telephones me in France where I live with my daughter. “Just in case you don’t know what to bring me for Christmas,” he says with studied casualness, “you could give me a calendar of Eurydice pictures.” Pause. “You know, like you did last year. I love those pictures of the baby girl more than anything in the world.”

It is testimony to the tenderness and greatness of my dad’s heart, to his capacity for transformation, his arresting ability to transcend his own boundaries, to grow and discover—that he fell in love with Eurydice the moment he laid eyes on her—and stayed in love no matter what the cost.

It was an improbable alliance. My dad, the cerebral scholar and intimidating intellectual, and the little girl with an intellectual disability. My dad, the tall, slender triathlete, and the chubby 1-year-old with down syndrome who immediately got leukemia and dragged her loved ones into a horror story of hospital isolation rooms, chemotherapy, and blood transfusions. The 2-year-old who couldn’t stand or crawl (much less walk). The 3-year-old who was not yet even ready to start potty training. The sphinx-like 4-year-old who still can’t say “How are you?” in any language, though she regularly hears half a dozen.

My ordinarily proud father didn’t care a whit about those “deficiencies.” What he saw was my girl’s soul—which is full of love and joy, high-spirited mischief, laughter, tenderness, and “Zaertlichkeit”, as he said in German—and which quickly became the center of his life.

Courtesy of Cristina Nehring

My dad would take Eurydice everywhere when we were visiting in Los Angeles. He’d take her to his office, to the park, to the opera, to the market, to the hardware store, to the homes of his doctoral students. He basked in the attention she garnered from passers-by in the supermarket. “It takes us 20 minutes to go 20 meters,” he remarked in his journal. “All the women in West Los Angeles are crazy about Eurydice. It’s great fun being out with her, but the best part is when I am finally alone with her again.”

My dad cut Eurydice’s fingernails and blew-dry her hair. He read her story books, made her fresh carrot and beet juice, circle-danced around the living room with her, and talked about her so incessantly that I—as her mother—was embarrassed. I recall with mortification this last summer in Sardinia: Every day he would regale the childless young couples and adolescent jet-setters on the sunbeds at our side with elaborate accounts of Eurydice’s toileting antics. It simply did not occur to him that anyone could be less than riveted by every detail about his grandchild. To him, Eurydice was a superstar.

Now, Eurydice is a superstar, and it’s no secret that I can’t stop writing essays and books about her myself.

But sometimes—just sometimes—it takes a great soul to know a great soul.

A friend of mine who has a son with a disability puts it better than I ever could: “My son is a litmus test. The moment I introduce him, the angels flock and the assholes flee.”

By that standard, my dad’s been an angel for some time. Today he’s an angel for real.

I’d like to tell you one more thing. I’d like to tell you my father’s last request of me. It was after 9 p.m., and we were preparing for a night in the hospital, and I was asking him what he wanted me to fetch him from his house: pajamas, toiletries … and what about a book? Which book should I bring from his sprawling literary library?

His answer was unhesitant. “Pinocchio,” he said. He and my mom had given Eurydice an attractive, detailed version of the Pinocchio story for Christmas, but it was too long to read to her word by word. “I want to preread Pinocchio,” he explained, “so I can tell it to the Lovebug in my words when I see her next.”

My father never saw the Lovebug again—and I never fetched Pinocchio. Moments after this conversation, a new doctor arrived in the ER and discharged us over my mother’s and my loud protests. “Your dad probably just has a flu,” she said. “Have him take two Tylenol and sleep it off.” The next day, my dad was still sleeping. He’s still sleeping now.

Eurydice covered him with kisses as he lay beside his bed after the paramedics had given up at 7 the next morning. She caressed his cooling cheek as he had caressed her cheek so many times. She smiled at him gently as he had smiled at her, just the day before, with all the pain he’d been in.

My dad had the most radiant smile of any man I know. Eurydice has a pretty radiant smile, too. Somehow I hope the smiles of this unlikely pair are so wide that they touch each other.

There’s a lot of talk in my little world of being ready. Ready to commit to a relationship, ready to write your own syllabus, ready to potty train, ready to proceed to the next stage. “Readiness is all,” says even Shakespeare. Readiness is good, or so we are supposed to think.

And yet my dad was not ready to die. I am devastated to say—and I’m also proud to say—he was the unreadiest to die of any person I’ve ever met. He may have lived in a little house and driven a 30-year-old Volvo, but my dad was a man who changed, who widened, who loved, who explored, who drank life to the lees, who went the extra hundred miles for those he loved whether they were a promising young literary scholar or a toddler with down syndrome.

And perhaps that is the greatest counterintuitive lesson we can glean from Prof. Nehring: to be unready to die. To be planning a rendezvous in Paris when Death comes for you, to be moving to new continents, planting new trees, inaugurating new love stories with special kids, serving your wife the outlandishly expensive wine she likes—and reading Pinocchio in the ER.

Courtesy of Cristina Nehring

Not everyone who met my externally austere Germanic dad would have known he was such a bon vivant—but he was. When he died in the wee hours of Jan. 3, he had just marked the two calendars I’d given him for the holidays with yellow happy faces to distinguish them from the ones I’d made for my mother. He was preparing to hang them in his graduate director’s office. He loved those baby calendars so much, he’d repeated. But he sure didn’t get far in the year with them.

Now it is up to those of us who are still here to fill those calendars to bursting.