As the co-authors of Red Families v. Blue Families, we often give talks about the recent rise in what’s called the “nonmarital birthrate,” or the idea that more than 40 percent of children are now born to women who aren’t married. Sometimes at our talks someone will come up to us, confess his or her encounter with single parenthood, and say something like: “When my daughter got pregnant and decided to keep the child, we were OK with that because we are Christians. When she decided not to marry the father, we were relieved because we knew he would be bad for her and the marriage would never work.”

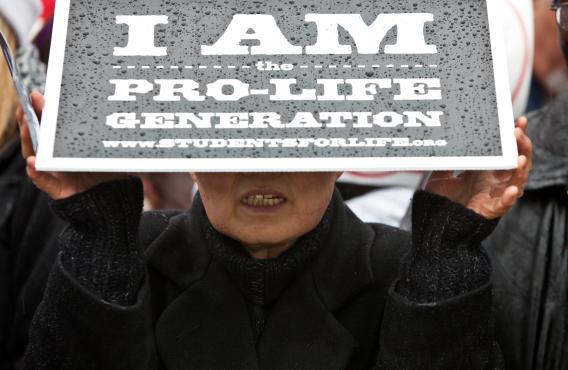

They express these two beliefs—that they are Christian and thus uncomfortable with abortion and that they are relieved their daughter decided to raise the child alone—as if they are not connected. But in fact this may be one of the stranger, more unexpected legacies of the pro-life movement that arose in the 40 years since Roe v. Wade: In conservative communities, the hardening of anti-abortion attitudes may have increased the acceptance of single-parent families. And by contrast, in less conservative communities, the willingness to accept abortion has helped create more stable families.

Researchers have considered many reasons for the rise in the nonmarital birthrate—the welfare state, the decline of morals, the increasing independence of women, even gay marriage. But one that people on neither the left nor the right talk about much is how it’s connected to abortion. The working class had long dealt with the inconvenient fact of an accidental pregnancy through the shotgun marriage. As blue-collar jobs paying a family wage have disappeared, however, so has early marriage. Women are then left with two choices: They can delay childbearing (which might entail getting an abortion at some point) until the right man comes along or get more comfortable with the idea of becoming single mothers. College-educated elites have endorsed the first option, but everyone else is drifting toward the second. In geographical regions and social classes where the stigma for having an abortion is high, the nonmarital birthrate is also high. Without really thinking about it or setting up any structures to support it, women in more conservative communities are raising children alone. This is a legacy the pro-life movement has not really grappled with.

In Red Families v. Blue Families, we pointed out the irony that blue states, despite their relatively progressive politics, have lower divorce and teen birthrates than red states. In fact the college-educated middle class, partly by postponing having children, had managed to better embody the traditional ideal: that is, a greater percentage of children being raised in two-parent families. In response, New York Times columnist Ross Douthat admitted that “it isn’t just contraception that delays childbearing in liberal states, it’s also a matter of how plausible an option abortion seems, both morally and practically, depending on who and where you are.” Although he conceded that “the ‘red family’ model can look dysfunctional—an uneasy mix of rigor and permissiveness, whose ideals don’t always match up with the facts of contemporary life,” he argued that “it reflects something else as well: an attempt, however compromised, to navigate post-sexual revolution America without relying on abortion.”

He’s right. The big secret very few are willing to discuss is that abortion rates do seem to correlate with greater commitment to marriage. Although the college-educated have a relatively low number of abortions, a higher percentage of their unplanned pregnancies end in abortion than for any other group. The college-educated almost certainly think of themselves as embracing the pill and resorting to abortion only in the relatively rare cases where contraception fails. Yet the bottom line is that the willingness to abort, however infrequently it occurs, makes it possible to reinforce the norm against having a child outside of marriage. Sociologist Averil Clarke points out that unmarried white college grads, who have maintained a 2 percent nonmarital birthrate for the last 20 years, terminate a higher percentage of pregnancies than other groups. And urban theorist Richard Florida finds that the higher a state’s abortion rate, the lower its divorce rate, with an even greater negative effect on the likelihood that residents will be married multiple times.

This creates the dilemma Douthat identified for those who see abortion as immoral. The Christian right preaches that contraception is not perfect, sex inevitably risks pregnancy, and abstinence provides the only solution. Indeed, as the number of abortions has dropped, the rate of unmarried women giving birth has increased. And nonelite young women often give their opposition to abortion as an explanation for why they went ahead and had the child, even if in other ways religion has not influenced them much. In their book Premarital Sex in America, sociologists Mark Regnerus and Jeremy Uecker report on a conservative, moderately religious young couple who have a child without marrying: “Some semblance of Christian morality may have prompted Andy and his girlfriend to keep their baby rather than elect abortion,” they write, “but beyond that, the evidence of religious influence on sexual decision-making is slim.”

So why do those wringing their hands over the rise in single-parent families never blame, much less even mention, opposition to abortion? They certainly mention everything else. Welfare comes up often as the killer of the traditional American two-parent family, even though there is very little evidence to support this connection. Sen. Daniel Patrick Moynihan, author of the 1965 study that called attention to the increase in black nonmarital births, pointed out that the change in family structure began before the expansion in welfare benefits and accelerated after they were cut. Indeed, nonmarital births continued to increase after the Aid for Families with Dependent Children program was abolished in 1996.

A second shibboleth has been same-sex marriage. In 2009, Maggie Gallagher observed in the National Review that in the preceding five years, the increase in nonmarital births “had resumed its inexorable rise.” She then speculated, “Is it mere coincidence that this resurgence in illegitimacy happened during the five years in which gay marriage has become (not thanks to me or my choice) the most prominent marriage issue in America—and the one marriage idea endorsed by the tastemakers to the young in particular?” Again, there is no evidence whatsoever that single-parent families have anything to do with same-sex marriage.

It is time to consider another possibility. If abortion is not an option, then more single-parent births are pretty inevitable. Think of it as the Bristol Palin effect, after Sarah Palin’s 17-year-old daughter announced her pregnancy shortly after her mother’s selection in 2008 as the Republican vice-presidential candidate. Republican women applauded the Palins’ choice to support their daughter’s decision to have the child. They wrote that unlike other Republican leaders, the Palins were sticking to their values rather than doing what others had done and quietly arranged an abortion. Democratic women were appalled—mystified why anyone thought having a 17-year-old raise a child was a good idea. Liberal and conservative women did agree on one thing, however: Neither group thought there was any point in having Bristol marry Levi Johnston, the father of the child.

Therein lies the rub. Moynihan argued in 1965 that the proximate cause of the increase in African-American nonmarital births was the disappearance of steady jobs for inner-city black men. Today, stable employment has been disappearing for all but the best educated men (and more recently for less educated women).

The big increase in African-American nonmarital births occurred in the 1960s and 1970s. For whites, the development has been more recent, and it has occurred at the same time as the emergence of anti-abortion sentiment as a key constituent of conservative political identity. Has the hardening of anti-abortion attitudes among white working-class conservatives helped cause the increase in white nonmarital births? Did it contribute to the erosion of the stigma on nonmarital births?

As scholars, while we suspect that the answer is yes, we have to admit that we have no definitive data. We do know that in spite of conservative denials, contraception reduces abortions and early births: A 2012 study found, for example, that providing women with free contraceptives resulted in lower abortion rates and lower teen birth rates compared with regional and national statistics. So we wouldn’t be surprised to find that a well-funded and influential anti-abortion movement contributed to the growth of single parenthood. Conservatives should at least start to be more open about whether this is a price they are willing to pay.