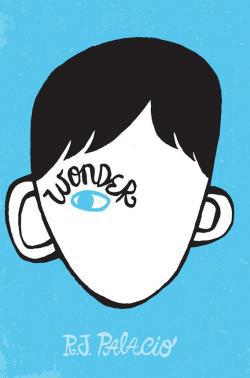

The book that has moved me most in the past year is Wonder by R.J. Palacio. It’s the fictional story of August Pullman, a 10-year-old with a very different-looking face—the result of a chromosomal abnormality and an illness—and his journey from the nest of homeschooling to the wilds of middle school. I listened to Wonder with my husband and my 9- and 12-year-old sons on a summer camping trip, and we spent hours mesmerized by the story and talking about the characters. Auggie knows that his appearance shocks people; he’s confronted constantly by that reality. Still, he’s got enough confidence to try to make friends. And over the course of his fifth-grade year, he’s rewarded for the effort. His perseverance came as an enormous relief to everyone in my family, because this is a children’s book, after all, and because the character had completely imprinted on our hearts.

My favorite thing about Wonder, though, is not that Auggie perseveres—it’s how unsparing the book is about the trouble he encounters along the way. For a time, the standard practice among the students at Auggie’s school is to wash their hands if they touch him accidentally. He overhears a boy he considers his best friend saying he’d want to kill himself if he looked like Auggie. His sister is loyal, but doesn’t want him to visit her high school, where she’s recently enrolled and for the first time has the chance to be just herself, instead of the girl with the brother whose face repels people. This is a book that makes you feel what it’s like to be Auggie, but also what it’s like to be the people around him.

R.J. Palacio is the pen name for first-time author Raquel Jaramillo, a book jacket designer in New York City. She launched an anti-bullying campaign called Choose Kind in connection with her book, and is ramping it up for National Bullying Prevention Month, which is now. I talked to her over the phone this week about Wonder and its message.

Slate: You’ve said that you got the idea for this book from a visit to an ice cream store with your two sons, when one had just finished fifth grade and the other was 3. They saw a girl with a facial condition like Auggie’s, and the 3-year-old started to cry, while your older son looked horrified. You got up and whisked your kids away, for the sake of the girl’s feelings, and you heard her mother say calmly, “OK, I think it’s time to go.” Afterward, you kept thinking about what you should have done differently. Why did this incident stay with you?

Jaramillo: I was really disappointed in my own response. It took me a whole book to figure out the answer, which has since been confirmed for me by parents of kids who look like Auggie. I wish I’d had the courage to turn around and look at the girl at the store. Even if my son kept crying, I should have just said, ‘I’m so sorry, my son’s not used to seeing people like you. What’s your name?’ Just simply acknowledged her instead of running away. That would have set an example for my kids. But I didn’t know how to handle it, and I think most people don’t. I responded from a point of fear in myself and I wish my natural default position had been to act out of kindness. But sometimes it takes work.

Slate: How did you decide what age Auggie would be?

Jaramillo: I really wrote the book with my older son and his friends in mind when he was in sixth grade. Middle school is often so fraught and it can be heartbreaking to watch as a parent. In a sense, it’s the first time kids are making their own choices about who they want to be. They’re pushing their parent away, which means they’re sometimes dealing with moral issues on their own. I also think there’s a universal aspect to Auggie’s experience at that age: We all know what it’s like to be an outsider and to have people talk about you behind your back—who hasn’t experienced that in middle school? I watched my son struggle with former friends who really betrayed each other, and more than anything I was dumbfounded by the lack of involvement of some parents. I kept hearing, “Let the kids work it out.” But at 11, they need reminding of who you want them to be. I think kids go home and they’re dying to hear from parents even if they pretend they don’t want to.

Slate: You show us lots of characters’ reactions to Auggie’s face from his point of view. All of them, I think, register some kind of shock and surprise. What were you trying to convey?

Jaramillo: I think it’s a really human reaction. We shouldn’t even feel bad about it. We’re conditioned to think of a human face as having certain proportions. Having spoken to people who look like Auggie: They know they look different. It’s when fear enters into it that they feel badly about themselves. Or it can get worse. One mom who has a son with a cleft lip told me about some girls on his bus who said, “I don’t want you to sit next to me, you’re too ugly.” That broke my heart. We have to get over that initial impulse and act with kindness. That’s the cornerstone of Choose Kind: It’s not about just “being nice.” There’s more effort required.

Slate: Alongside Auggie, several characters narrate chapters in Wonder, including his friend Jack, his older sister Olivia, and her boyfriend.

Jaramillo: I didn’t start out thinking I’d do that, but at a certain point, I wanted to get to know Olivia in particular. She had a lot to say. Also, I decided that to tell Auggie’s complete story, I had to leave his head. He’s limited in what he perceives. He’s adept at picking up how people respond to him, but not that swift in seeing the bigger picture, the full impact he has on other people. A lot of it goes on way over his head. On the other hand, I didn’t write from the point of view of any of the parents because this is a kids’ book, and that would have given it a darker tone. We only see Auggie’s mother from his point of view or from Olivia’s. They have no idea what she’s telling her friends over a martini at night.

Slate: Let’s talk about Auggie’s parents. Has anyone complained to you about how they’re idealized? I wondered, as I was reading, if the parents of disabled kids would read this and feel inadequate because these parents are never tired, never short-tempered, never anything other than devoted.

Jaramillo: No, I haven’t heard that. I’d emphasize that we mostly hear about them from the perspective of a 10-year-old boy, and when Olivia is narrating, she is more critical of her mother. I also have to tell you: I wanted to portray a very loving family. Justin, Olivia’s boyfriend, says that the universe takes care of all its birds, and what I meant is that yes, Auggie has a lot to deal with but at least he has this great family unit who adores him unconditionally. If you read between the lines, there are some cracks and stresses in that marriage, but these parents are functional in that they try to hide that part of it.

Slate: The character we don’t hear from, in the first person, is Auggie’s nemesis, Julian. He remains for us, I think, essentially a rotten kid with rotten parents. Did you think about telling any of the story from his point of view?

Jaramillo: I did. I started writing a chapter from Julian’s point of view, but the biggest problem Julian has is that he doesn’t want to get to know Auggie. So I found he was hijacking the story by turning it into his own. And you know, writing in Julian’s voice, a lot of mean stuff came out on the page, and I didn’t want to give a platform to a bully. And for me to give him an epiphany about Auggie—that didn’t feel true to Julian’s character or to life. Not everyone can change in a year. I wanted Julian to cheer for Auggie, but I thought, no, if I’m telling the truth then Julian would be fuming or not getting it.

Slate: One of the great strengths of this book—maybe my favorite thing about it—is that you show people who love Auggie saying terrible things to him and about him. Olivia doesn’t want him to go to her school play. When his friend Jack says he would kill himself if he looked like Auggie—to other kids, in the cruelest way—Auggie overhears him. It’s a crushing moment. But Auggie recovers, and his friendship with Jack recovers! Why?

Jaramillo: That was definitely a deliberate choice on my part. I remember being a kid, and I think most adults have this moment, when you think about something you wish you hadn’t said and it still makes you shudder. Also, I wanted to say something about forgiving people: about how you can move on when a friend is mean for a couple weeks—even really mean—and then turns around. I wanted to show all the range we have as people.

Slate: Right. One way I think you do that is to show how the attitude toward Auggie at school gradually softens.

Jaramillo: Yes, the kids themselves get tired of it, of the chorus of meanness. I think there also comes a moment in a lot of kids’ lives when they decide, who am I going to be? I don’t like the way I feel when I’m with this mean kid. Sometimes it’s a painful moment because you have to choose to be alone.

Slate: How have kids with facial anomalies, or disabilities, responded to the book?

Jaramillo: I’ve gotten the most amazing emails and notes and blog posts. I’ll send you one. You know, a lot of people are surprised I don’t have a child with this kind of condition. But I really do think all of us can imagine what it would be like if we try.