With less than two months before my wedding, I am a fearless groom, ready to feign interest in things I have spent 38 years pretending did not exist: DJs, letterpress, flowers. But there is one aspect of the coming wedding that has turned me into Mr. Kurtz, in Heart of Darkness, crying out in a whisper no more than a breath.

The hora, the hora.

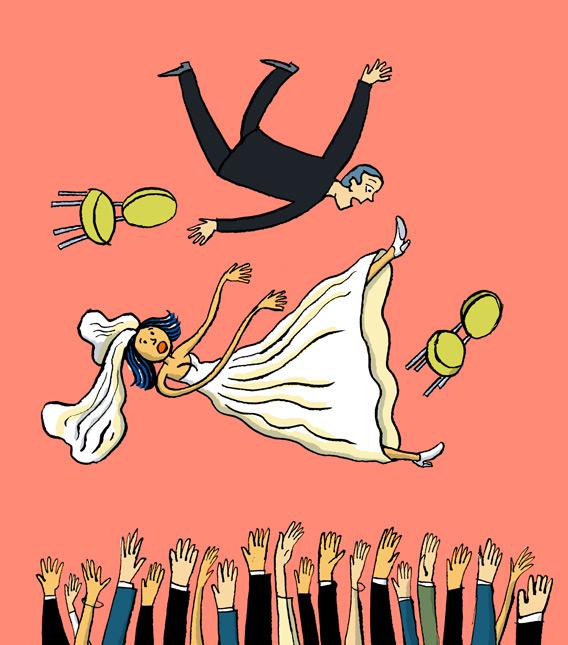

“Hava Nagila,” the circle, the bride and groom being lifted on chairs, the hand holding with sweaty cousin Bernard: It all makes me queasy. But to everyone—the Intended included—it is beyond question that we will dance the hora at our wedding. If cheese from a ham sandwich fell on my shrimp cocktail at high noon on Yom Kippur, eating the shrimp would be a personal choice afforded me as a modern secular Jew. But if I don’t dance the hora at our wedding, I am letting Mel Gibson win.

The hora partisans I know seem uniquely concerned with “preserving” the hora despite ignoring or loudly disagreeing with thousands of other Jewish beliefs and precepts, including, in a curiously large number of instances, the existence of God. (I don’t know if God exists, but I do know that if he doesn’t, he doesn’t care about how I dance.) These hora fanatics try to silence my curmudgeonly grousing with that magic word, Tradition!, and are unmoved when I note that stoning has a pretty long tradition too.

They are also unmoved when I explain that the wedding hora with the lifted chairs is the meatball parm of American Judaism—recent, misunderstood, mish-mashed, and prone to cause great bodily harm. To clear things up: I have no fear of being lifted by hammered people. And I’m completely comfortable with my religion, which is, officially, “Jewish enough.” But the hora isn’t even Jewish. It’s Romanian. According to the International Encyclopedia of Dance, the hora’s many variants (the Sunday hora, the fir tree hora, the straight hora, the young maiden’s hora, the tinsel hora, etc.) have long played central roles in three-day wedding celebrations, adulthood ceremonies, and other rituals of Romanian village life. The hora became specifically “Jewish” in Palestine-turned-Israel in the last 100 years or so. It arose from a natural selection process among various imported Eastern European folk dances such as the krakowiak, sher, cherkessia, and polka to become Israel’s iconic dance. Some ascribe its success to the popularity of the “Hora Agadati” by Baruch Agadati, a Jewish-Romanian modern dance choreographer. The first performance of Agadati’s hora was in 1924 in Palestine—the same year my grandfather, who will be at the wedding, turned 10 in Milwaukee. Other authorities, like the late Rivka Sturman, a kibbutznik choreographer quoted in Seeing Israel and Jewish Dance, noted that there was something in the hora—an energetic, egalitarian, close-knit dance—that made it the best means “of expressing the enthusiasm of building the country together.” It couldn’t hurt that it was easier to spell than krakowiak.

Somehow, a new Israeli folk dance collided with a completely separate Jewish dance tradition, the lifting of the bride and groom on chairs, to become a centerpiece of the contemporary American Jewish—and, oy, occasionally non-Jewish—wedding. (As in all things Jewish since 1964, the likely suspect: Fiddler on the Roof.) So where did this chair-lifting come from? While The Knot starts its cringe-inducing, Romania-ignoring description with “the Hora, or chair dance, most likely derived from the tradition of carrying royalty on chairs,” the lifting of the bride and groom—and increasingly the parents of the bride and groom and probably somewhere the pets of the bride and groom—comes from Eastern European Orthodox Jewish rituals. In those traditions, the married couple, being careful not to touch, is raised to hold a handkerchief on either side of the mechitzah, the partition between men and women at the wedding. Our wedding will not include a partition, given how awkward it would be to see dozens of primarily straight men dancing alone to “Mustang Sally.” Also, this is the 21st century. I am befuddled why this specific tradition, rooted in gender separation, has not been targeted for eradication by the normally feminist hora proponents in my life, who when not busy accusing me of hating God and kugel are otherwise occupied burning Rush Limbaugh in effigy.

I grant the legitimate responses to my objections. I understand that a Jewish tradition doesn’t need to come from the Bible to be authentic. (Frankly, everything I know about biblical dancing comes from Kevin Bacon in Footloose.) I know that just because you won’t be able to find a meatball parm in a chic Roman trattoria doesn’t mean that tomato sauce, mozzarella, balled meat, and bread aren’t Italian. Indeed, the Talmud says that it’s obligatory to dance at a wedding, for the bride’s happiness. Beginning in the 12th century, the tanzhaus, large halls specifically built for wedding dances, became central features of Ashkenazi Jewish life. Hasidic and other Orthodox Jews take very seriously the commandment to dance at weddings, known as mitzvah tanz, which has led to a YouTube sub-genre that, however impressive, is unlikely to pull global viewers’ attention away from more important issues, like college athletes van-dancing to intensely forgettable pop songs, any time soon.

The joyous tradition of Jewish dancing is something I admire. And it’s certainly better to dance in a circle than bunny-hop like Presbyterians. Still, the hora annoys me. In this meatball-parm-and-reuben-sandwich world, where most religious and cultural traditions are a mix of history, commandment, and unadulterated bogusness, almost all of us pick and choose which customs to follow. When the yentacracy declares out of nowhere that one of those customs—this random Romanian roundelay—is an essential expression of Jewishness, I feel bound to object, especially when that custom is a half-invented semi-chauvinistic nontradition tradition that entered the annals of Jewish life, in its current form, not at the time of Moses but at the time of Sandy Koufax. Also, I don’t want to hold hands with sweaty cousin Bernard.

With all this on my side—facts, history, a commitment to intellectual consistency—I continue to work on the Intended, explaining, pleading, occasionally whining that if we start fully accepting all the rules of the Talmud and stop touching each other and move to Israel and learn Romanian and install a fir tree in a wedding hall, only then can we authentically and full-heartedly dance the hora at our wedding.

And she continues to say, be careful, my love, not to fall off the chair.