Turn on your TV tonight. Or tomorrow. It doesn’t matter whether we’re talking network or cable TV, quality or schlock. The odds are good you will see a divorced mother. On TV, if nowhere else, divorced and separated moms are the demographic of the day: Cougar Town, Breaking Bad, Parenthood, Mad Men, Californication, Damages, Hung, The Good Wife, and now I Hate My Teenage Daughter all feature divorced or divorcing mothers. The marital backstories run the gamut from happily sharing custody to abandonment by a deadbeat dad (usually a musician), to newly separated (with the lingering possibility of reconciliation), to remarried.

Why all these divorced mothers on TV? The obvious answer would be because lots of mothers get divorced. Logical though that point may be, it doesn’t explain why the existence of divorced mothers has eluded other media, from popular magazine articles and nonfiction books to movies and novels, all of which have, with few exceptions, strangely glossed over divorced mothers in recent years. If the conventional wisdom is that television lags behind other media when it comes to cultural depictions, in the case of divorced women this dynamic has been upended: These shows are the early adopters.

Divorce is not new, of course, and discussions of it go in waves. On television, divorced mothers have been around since I Love Lucy; One Day at a Time and Kate & Allie were also about mothers without husbands. But this history only makes it more notable that the early 21st century was so lacking in depictions of mothers without husbands. I know, because I have been on the lookout for them since I divorced 10 years ago, when I was 34 and my son just 2. As part of the college-educated demographic that divorces at a lower rate, and as part of a Generation X that delays marriage and kids (and, by extension, divorce), I found myself suddenly bereft of examples of women in similar situations, whether real or fictional.

Dutifully and desperately I searched the card catalog for divorced-mother literature. The “mommy wars” were being waged in books like Judith Warner’s A Perfect Madness: Motherhood in the Age of Anxiety, Alison Pearson’s novel I Don’t Know How She Does It, and Caitlin Flanagan’s To Hell with All That: Living and Loathing Our Inner Housewife. Divorce barely made the indices of these books, though. The only mention of it in Warner’s thorough book about overparenting amongst the middle classes came when she suggested that a mother’s greatest fear was to be “an unhappy mom. A divorced mother, perhaps, who is crippled with worry over money.” Caitlin Flanagan, writing decades after joint custody became normal, wrote that children should “wake up every morning to see a mother’s face.” Long magazine articles on “The Opt-Out Revolution” failed to even raise the obvious, lurking question: What if the mother’s marriage fails? This despite the fact that writings by single mothers by choice were coming into vogue. The ensuing years have been little better. How can you be a Tiger Mother if your daughter’s viola lessons fall on the night she is with dad? Even dogged feminists seem to have punted on divorce: When did you last come across any prominent discussion of child support or joint custody laws (pieces about dads’ rights excepted)?

Recent movies are almost as bad. The best-known divorced mothers in film remain very last century—the vilified Meryl Streep character in Kramer vs. Kramer or the streetwise Julia Roberts character in Erin Brockovich. It seems somehow fitting that even the excellent 2005 movie The Squid and the Whale was set in the 1980s. Novels, too, are surprisingly thin on the topic, making 2011’s Stone Arabia, by Dana Spiotta, a welcome surprise.

Which brings us to television’s sudden, salutary spate of mothers who are divorced (or at least separated). They are so plentiful that they can be broken down into subtypes. We have Cougar Town’s Jules, a successful real estate developer in a gleefully recession-free Florida, with a charming, well-adjusted son and a chummy if somewhat unbelievable relationship with her cheating, unemployed ex, whom she happily supports. On Parenthood we watch Lauren Graham’s Sarah go through familiar motions: She’s the girl who fell for the bad boy too young and is now raising troubled teens on her own, while hoping to find a nice guy. Skyler in Breaking Bad and Karen in Californication are struggling through the craziness of separation while raising teenagers (and, in Skyler’s case, a baby as well). For both, reunion with their estranged husbands is still a possibility.

Divorced mothers on television are so ubiquitous, indeed, that they are unremarkable, and unremarked upon. Even Mad Men, that nostalgia-fest for conventional femininity, allowed Don and Betty to divorce. And the latest entry into the divorce stew, I Hate My Teenage Daughter, uses divorce as a casual plot device, one that allows it to plunk two insecure moms on the same couch, where they can make weight jokes and commiserate about how their daughters treat them. Meanwhile, Louie, one of TVs best comedies, is about the daily life of a divorced dad.

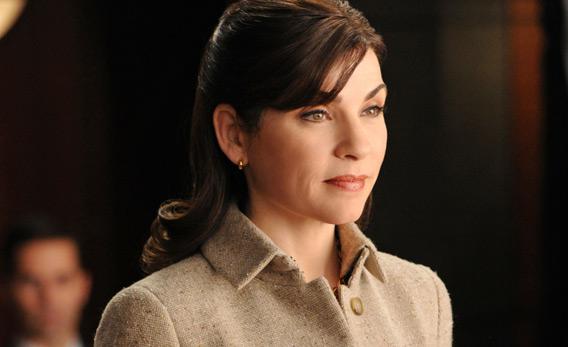

The best of the lot, even though its protagonist isn’t actually divorced (at least not yet), is The Good Wife. Juliana Margulies’ Alicia saw her happy marriage implode in the pilot, but on this show, there is no jaunty ensemble of girlfriends and neighbors to blunt the loneliness that follows her separation—though she did sleep with her boss, at least for awhile. Nor is the effect of having a womanizing husband papered over. (All over the paper is more like it.)

While Alicia gets overwhelmed, she never plays the harried single mother. She is annoyingly competent, a trait consistent with having been a politician’s wife. She has a pleasant yet businesslike relationship with her children’s father, who is a cad but not all bad. And in the most recent episodes, she is acquiring some serious feminist credentials—looking for friends, not a man, and considering getting on the partner track, work/family balance be damned.

The Good Wife has figured out that important feminist questions can be asked by seeing what happens after wives, and marriages, are no longer good. Divorce also creates gripping problems and plotlines, as the current shows, and their alternately ludicrous and wrenching stories, prove. Even on Louis C.K.’s grim Louie. In one scene, Louie and a divorced mother hang out while their kids are on a play date. They huddle in the bathroom, drinks in hand, blowing cigarette smoke out a window. “Who wants to hang out with divorced people?” the mother asks Louis. “We’re all lost.”

This season, it seems, a lot of people want to hang out with divorced people, at least on TV.