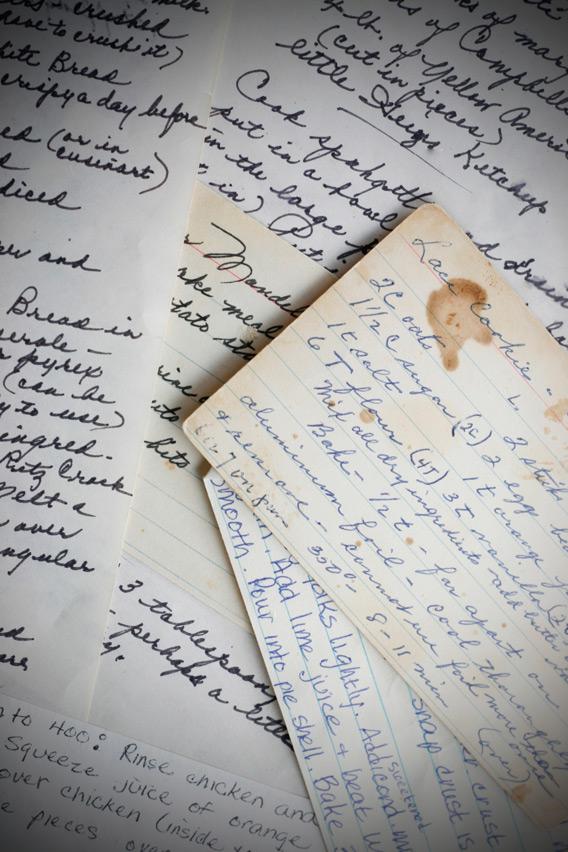

When my great-grandmother Pauline died 20 years ago, my mother requested only one item from among her possessions: her old recipe file. Not that Mom needed it for practical reasons; by then she’d known for decades how to make the sour cream raisin pie and overnight rolls and boiled fudge described therein. What she wanted instead was the history. Tucked inside the file were photos and notes, mementos from a life that encompassed a long marriage and two continents and children who had gone on to have their own children (who, by the time Pauline died, had become parents themselves). The file was rich with evidence of its owner, and of its frequent use: It was spattered with grease stains and marked with thumbprints, and the crabbed hand in which it was written had visibly deteriorated between the first recipe and the last. My great-grandmother was a stoic German woman; she wouldn’t have poured her heart into a diary. So this file was the nearest approximation, the most intimate thing she left behind. But it was bigger than just Pauline: It was also an accidental charter of our family’s traditions, rendered in 3-by-5-inch index cards.

My mother makes that sour cream raisin pie most every Thanksgiving, and it signals the arrival of that time of year when a goodly portion of the population hauls out the dishes that, for better or worse, make the holidays complete—stuff we may understand intellectually to be archaic and categorically unhealthy and in some cases downright bizarre, but that, even apart from their deliciousness, simply must be made for Thanksgiving to be Thanksgiving, or Christmas to be Christmas. (Speaking of unhealthy and bizarre, take my mother’s Holly Berry cookies: cornflake clusters shellacked in marshmallow goo she dyes green with food coloring, then garnished with Red Hots.) Since most of these treats appear only once a year, for many of us creating them it means hauling out the grandma-certified documents that explain how they’re made.

If you’ve still got any, that is. As the shiny touch-screen device in your purse has all but replaced your phone book, address book, calendar, notepad, magazine, novel, and newspaper, I hardly need to point out that we don’t much bother with paper anymore. If we have recipes clipped, we have them in a file on our desktop, or in what the Epicurious iPad app calls—irony of ironies—My Recipe Box, which is comprised of digital index cards. (They’re even lined in college rule with tabs at the top, just like real cards.) It’s curious that 3-by-5s remain the signifier for a treasured recipe, despite the fact that in the last 80 years, they seem to have gone from ubiquity to impending extinction.

Between Roman times and the 19th century, women typically passed down their recipes to younger generations by example. But as literacy became more widespread over the last 200 years, women slowly shifted to writing their instructions down. So says Sandra Oliver, former publisher of Food History News. “The earliest examples of written recipes are to our modern eyes exasperatingly terse,” Oliver told me. “They say things like, ‘enough flour to make a stiff dough’ or ‘bake until done.’ Some are just lists of ingredients, without quantities. They were meant merely to jog the memory of making these dishes with one’s mother—you knew what ‘enough flour’ meant because you’d seen her put in that amount.” But near the turn of the 20th century, as scientific progress revolutionized many aspects of daily life, the desire for precision trickled down to the American housewife. “Recipes became more formalized,” Oliver said, “and you started to see women’s magazines talk more explicitly about nutrition science.” Suddenly, magazines were name-dropping terms like nutrients, metabolism, and, my favorite, carbonaceous materials, which we modern folk would call carbohydrates.

These magazines played a critical role in the rise of the recipe card. As a more precise recipe format gained traction, magazines recognized an opportunity: They began offering readers subscriptions of recipes printed on heavy cards branded with the magazine’s logo and mailed out every six to eight weeks. Between the 1930s and the mid-’90s, few women’s magazines neglected to offer this service, which delivered regular installments of full-color, uniformly sized recipe cards to your door, divided into categories like “entrees,” “starches,” or “vegetables & sauces.” (If you signed on with an especially generous outfit like Life, they’d even send you a wooden box to keep them in.) The magazines’ food advertisers got into the act, too, offering recipe cards that wrote brand loyalty right into the recipe: Sunkist’s citrus-based recipe cards directed you to use their oranges and lemons.

However much trust women may have placed in the test kitchens of Ladies’ Home Journal or McCalls, ultimately they went on to write out their own recipe cards, swapping them with friends and sisters and daughters, and commemorating their origins with titles like “Mrs. Johnson’s Coffee Cake.” The ritual of keeping recipe cards seems to be rooted in the same impulse that makes us keep shelves of books we’ve already read and snap photos of every vacation we take: We like to remind and reassure ourselves of that which we already know. “The idea of the recipe card was that you were building a treasury of your knowledge,” said Amy Bentley, associate professor of food studies at New York University. “When I was in Girl Scouts, we did the same thing. As we cooked new dishes, we’d record the recipes. It served as a kind of card catalog for the knowledge you’d gained.”

But the knowledge the cards evoke isn’t limited to the information contained in their step-by-step instructions. My mother could’ve made Pauline’s sour cream pie with her eyes closed, but what she couldn’t conjure as easily, once Pauline had died, was the pie’s intangible context, the years of experience and life and circumstance that had brought it to our family. Holding Pauline’s recipe as she stirred and sifted let my mother recall the precious intangible ingredients with which the finished product would be imbued. Pauline’s recipe file was, like those inexact recipes of yore, the thing that jogged her memory.

The info-hoarding impulse that filled all those midcentury filing boxes with index cards hasn’t changed, of course—but what we do with it has, and radically. It’s the same urge that now inspires me to check Smitten Kitchen and Serious Eats each day, and that has resulted in the prodigious stack of food magazines in my living room. Over time, magazines and online recipe sites have displaced our reliance on family and friends for sustenance, supplying us instead with new culinary idols. Even though I’ve never made Grandma Pauline’s bean soup with dumplings, I’ve made Tyler Florence’s corn chowder—and that makes me sad. Sadder still, if we’re swapping recipes these days we’re probably doing it via email, sending off these fragments of our personal histories to be archived or deleted once the brownies or meatballs or enchiladas are made, replacing our handwriting with the hollow uniformity of a sans-serif font. (Also it’s a lot easier to make a typo—like the time my autocorrect told my best friend to put 1T of cumin into my homemade barbecue sauce, instead of 1t. “This sauce tastes like B.O.,” she later replied.)

The recipe card may be in dire peril—but it’s not quite dead yet. Take Martha Stewart Living, which hasn’t yet given up on its tear-out recipe cards even now that it has iPad apps full of recipes. And besides, isn’t the recipe card, like ’60s fashions and the classic cocktail, the sort of thing our nostalgia-obsessed culture might want to revive? Already, there are all kinds of charmingly retro recipe cards and templates available for purchase (like this one, or this one, or this one, which I’ve been using to record my own best dishes).

I like the idea of bringing the recipe card, in all its grease-smudged idiosyncratic glory, back from the brink. And I especially like the idea of my great-grandkids flipping through my own box of recipe cards after I’m gone, touching paper my fingers touched and admiring my as yet un-crabbed penmanship. And then, in all probability, they’ll wrinkle their noses at the juxtaposition of the words boiled and fudge, before hopefully making it themselves.

* * *

Slate readers, please join us in celebrating the recipe card by scanning and emailing in an original, handwritten card spelling out a recipe for any holiday dessert that has been handed down in your family through at least two generations. (So, a card your grandmother wrote out counts; one your aunt wrote doesn’t.) We want to see it all: Recipes that are archaic, beloved, categorically unhealthy, and downright bizarre; we want butter stains; and we especially want beautiful penmanship, Send them to us at doublexmail at gmail dot com by this Sunday, Dec. 18, together with a few lines about their provenance, and we’ll publish our favorites in a slide show next week. (We will use your name unless you specify otherwise.)

See more food articles at delish.com: