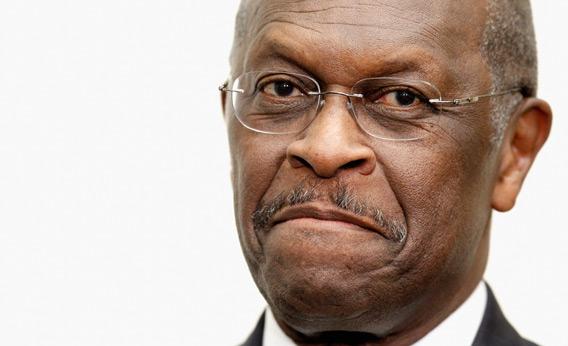

As Herman Cain discovered this week, today’s political candidate has a new means of saving face should he find himself facing an insurmountable obstacle to victory. If he wants to drop out of a race or back away from considering a run, he needn’t admit weakness, not anymore; all he needs to do is pass the buck and blame his wife. Cain did this on Wednesday, when, in the wake of allegations that he had a lengthy extramarital affair with a woman named Ginger White, he said that he needed to discuss the fate of his presidential campaign with his wife, Gloria Cain.

“I will do that when I get back home on Friday,” Cain told reporters. “I am not going to make a decision until after we talk face-to-face.”

How awkward for Gloria. But while Cain’s use of the wife-as-escape-hatch strategy may be particularly egregious, he isn’t the first to lay this sort of responsibility at his spouse’s feet. Earlier this year, when Indiana Gov. Mitch Daniels announced that his wife and daughters—“the women’s caucus,” he called them—had vetoed a presidential run, the reasoning actually sounded believable, given Cheri Daniels’ well-documented aversion to the spotlight and the growing media attention to the Daniels’ past marital problems. (In the ’90s, she divorced Mitch, married another guy, and then came back.) Mississippi Gov. Haley Barbour didn’t directly invoke his wife in deciding not to run earlier this year, but he hardly needed to: Unnamed family friends did that work for him, telling reporters that she was a definite factor in the decision. (“Marsha absolutely didn’t want him to do it,” one told the Daily Beast,)

Can you imagine, say, 1980s-era Bob Dole invoking Liddy as the reason he was backing away from a run? Not too long ago, it would have been unthinkable for a candidate to tell the public that his wife had vetoed a presidential campaign. In part this is because such a move might have been considered wimpy, but the change is also a sign of how much our assumptions about the role of the campaign spouse have shifted. The Reluctant Wife excuse resonates because we have come to expect that politicians and their spouses may have divergent careers and interests, and because we know just how often spousal smiles are faked. When Richard Nixon invoked Pat in his 1952 Checkers speech, it wasn’t to blame her for the fact that the future of his vice presidential run was in question; it was just to point out that she, like he, was not a quitter. “After all, her name was Patricia Ryan and she was born on St. Patrick’s Day, and you know the Irish never quit,” Nixon said.

Politico has suggested that the move toward open discussions of how candidates’ wives feel is a sign that politics is becoming more honest, and that may be. “Campaigns have altered their expectations for spouses and are moving toward more realistic and authentic expressions of their family circumstances,” Molly Ball wrote earlier this year. But the Reluctant Wife excuse is also a matter of strategy and convenience, a kind of shorthand that stops further questions. In this sense, the strategy recalls the way politicians and CEOs always claim they’re resigning to spend more time with their families. It’s not necessarily that the excuse isn’t true, but it may not be the entire story.

The wife-as-escape-hatch, if artfully done, can work on two levels. It makes a candidate seem attentive to his wife’s concerns, but suggests no diminution of his own testosterone-fueled ambitions. It’s the campaign-trail equivalent of the swaggering guy who threatens to take a swing at another guy in a bar, but manages to avoid the fight by bellowing ”Hold me back!” He gets to be manly and competitive and a good guy, all at the same time. In February, as he was mulling an entry into the 2012 presidential race, South Dakota Sen. John Thune mentioned to a reporter that his wife had read Game Change, the exposé on the 2008 campaign that painted Elizabeth Edwards as a power-mad harpy. “It was not helpful,” Thune said, laying the groundwork. A few weeks later, he announced he wouldn’t run. Without having implied that he lacked that vaunted fire in the belly, Thune, who’s only 50, might theoretically consider a future run. After all, as far we’re concerned, he’s just as ambitious as he ever was. And as for his wife, she could yet have a change of heart.

The problem with this strategy, though, is that it puts the candidate’s interests at odds with his wife’s in a most public way. If the candidate doesn’t run, it’s she who’s to blame. If he does run, everyone knows her heart isn’t in it. And running a campaign with an openly reluctant spouse is like running a campaign in which the candidate is feuding with the campaign manager—you can do it, but it won’t go well. That’s why in practice, the Reluctant Wife Excuse is typically the prelude to an exit, a means of letting supporters down easy. If you hear a candidate or a candidate’s spouse setting the scene for this exit, say by discussing how much the spouse despises the campaign trail, refrain from any hasty donations.

Which brings us back to Herman Cain. Having now cited Gloria as a potential stumbling block to his continued candidacy, and having previously discussed the need to “reassess” that candidacy, it’s hard to imagine that he plans to do anything other than drop out. And that’s precisely the problem with his use of the Reluctant Wife Excuse: He comes off as a guy who knows he needs to leave the race but just can’t bring himself to say the words. His ego won’t let him. So Gloria is his out.

What an awful lot of pressure for Gloria Cain. She’s made few public appearances during her husband’s run; her introduction to the nation was explaining to Greta Van Susteren that her husband was not, in fact, a serial sexual harasser. Now, her husband has thrust her into the spotlight again, telling everyone she’s responsible for a decision that’s rightly his.

Which is why, when Herman Cain goes home today, he should call his family meeting, and talk things over with Gloria and his kids. But when that’s done, he should go in front of the cameras and say that he’s made a decision. End of story. As most CEOs can tell you, you’re the boss, you take the hit.