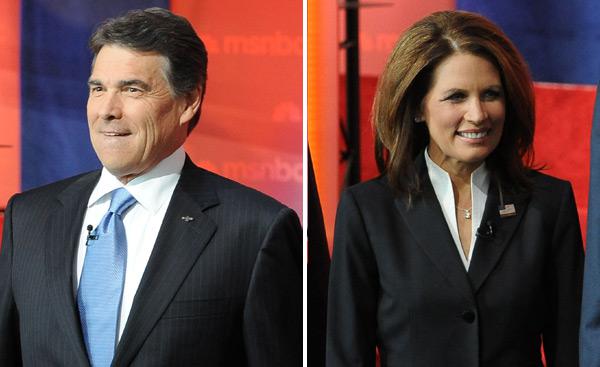

Michele Bachmann has lately fallen on hard times. Since her big win at the Iowa straw poll in August, Bachmann has endured a lack of campaign funds, the insults of an ex-campaign manager, underwhelming debate performances, and, most important, the loss of supporters to Rick Perry. On paper, Bachmann and Perry have a lot in common: They both appeal to the socially conservative and Tea Party factions of the Republican Party, they’re both evangelical Christians, they both support low taxes and low spending, and they’ve both been called out for major gaffes on the campaign trail.

One marked difference between the two is obviously their gender. And while it’s hard to say whether Bachmann’s decline in the polls has anything to do with the fact that she’s a woman, it’s easy to see some differences in the way the media treats the two candidates. Pundits may equally denigrate Perry when he says Social Security is a Ponzi scheme and Bachmann when she says the HPV vaccine causes mental retardation, but there is a subtext to some of the criticism: Bachmann is too fragile to lead.

The infamous Newsweek “crazy eyes” cover perfectly encapsulates the dominant narrative about the candidate. Progressive bloggers go on MSNBC and call her “crazy,” (in Rolling Stone, Matt Taibbi ups the ante and calls her “batshit crazy“). Crazy is not a quality that anyone wants in the person potentially dealing with nuclear weapons.

Perry, meanwhile, comfortably fits into the Republican archetype of the stupid male candidate. We had a former Texas governor in the White House for eight years who took pride in his anti-intellectual cred—it made him more relatable. As Steve Benen at Washington Monthly points out, Perry even took a page from the Bush playbook by bragging about his crap grades at Texas A&M. Though the Houston Press may have a random generator of dumb things Rick Perry says, this sort of admission tends to draw cheers from conservative audiences.

Of course, it’s just as easy to make the argument that Perry is crazy and Bachmann is stupid. As Rebecca Traister, the author of Big Girls Don’t Cry: The Election that Changed Everything for American Women, points out, a lot of Bachmann’s early gaffes—that the Revolutionary War started in New Hampshire (that would be Massachusetts), that John Wayne was born in Waterloo, Iowa, (that would be serial killer John Wayne Gacy)—were more “stupid” than “crazy.” Conversely, to many secular Americans, Perry’s ties to religious groups that claim that Texas is “the prophet state” sound, well, crazy.

Then there is the way the media has dealt with the health issues both candidates have faced. The dust-up over Bachmann’s alleged migraines emphasized her femininity: Would she be able to handle the many high-pressure decisions and controversies that come with the presidency? Perry’s back troubles, in contrast, have been used as fodder for speculation about his lackluster debate performances or as a starting point for a debate over the medical use of stem cells. (He received an injection of his own stem cells as part of back surgery in July.)

Yes, Traister says, we’ve come a long way since 2008 in indentifying sexist doublespeak. (Recall that Hillary Clinton was called shrill, a nag, a she-devil, confronted with “iron my shirt” posters, and so on.) And as long as the Republican debates include just one woman and one black man along with six (or seven) white guys, the non-white-dudes are going to stand out. Still, it matters how those differences are described. Whether a candidate is crazy or stupid may not be the most edifying debate of the 2012 campaign. But it may help us separate our views of the candidates from our prejudices about them.