Looking for the perfect baby-shower gift for a certain well-dressed duchess? Consider Kay Goldman’s new book Dressing Modern Maternity, a history of the Page Boy maternity label. The groundbreaking Dallas clothing company was founded in 1938 by the three Frankfurt sisters, who were frustrated with the limited options in maternity wear. Combining stylish design with innovative business practices, Page Boy dominated the maternity market for five decades. Jackie Kennedy, one of the first victims of “celebrity bump watch,” was a Page Boy client; so was Elizabeth Taylor.

With two more paparazzi-friendly pregnancies–Cambridge (ongoing) and Kardashian (just ended)—putting maternity fashion in the global spotlight, it would seem that the timing of this release couldn’t be better. There’s just one problem. As Women’s Wear Daily recently pointed out, both Kim and Kate joined the growing ranks of mommies-to-be who spurn maternity clothes in favor of adapting their pre-pregnancy wardrobes or buying slightly larger versions of the kinds of clothes they usually wear—and, with minor alterations, could wear again after the baby arrives.

This isn’t just recessionista chic; for most of the history of fashion (and motherhood) expecting moms have managed just fine without maternity clothes. The relatively high cost of textiles in the pre-industrial age made it impractical to wear any article of clothing for just a few months; most pregnant women wore their everyday clothes, altered or made with extra material that could be let out or taken in with frequent childbearing. It wasn’t until the early 20th century that women began buying clothes expressly designed for two. Maternity clothing, then, is a fairly recent phenomenon, and a close reading of Dressing Modern Maternity suggests that its days are numbered.

It’s a common misconception that “in previous centuries women secluded themselves during pregnancy,” Goldman writes. Pregnancy was an open secret, and clothing neither hid nor advertised it. By the mid-19th century, however, changing cultural norms and medical opinions meant that visibly pregnant women often lived sheltered lives, if they could afford to; when they ventured out, patented “maternity corsets” kept bumps in check.

As women became more active outside the home in the early 20th century, the question of what to wear during pregnancy grew more urgent. One of the first firms to market maternity clothing was Lane Bryant, launched in 1904 by dressmaker Lena Bryant (the bank misspelled her name when she opened her business account, and it stuck). Bryant’s simple, inexpensive maternity dresses were adjustable, but did not solve the problem of uneven hemlines as the tummy expanded and fashion dictated ever shorter skirts.

In 1937, Dallas secretary Edna Frankfurt Ravkind was pregnant with her second child and unable to fit into her usual elegant wardrobe. With true sibling camaraderie, her younger sister, Elsie, told her she looked like “a beach ball in an unmade bed.” Three days later, Elsie—who had studied accounting and design at Southern Methodist University—had cut up one of Edna’s pre-pregnancy suits and remade it as a maternity ensemble in the slim silhouette of the day. Within months the sisters opened their first boutique, strategically situated on ground floor of the office building housing most of the OB-GYNs in Dallas. Little sister Louise, a fashion design major, joined the family firm in 1941. The company’s name came from its logo of a page boy blowing a trumpet to announce the birth of an heir to the throne.

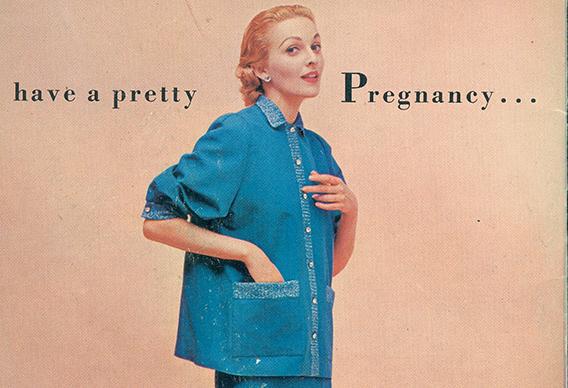

The secret to Page Boy’s success was Elsie’s patented skirt design, which fit snugly around the hips without hiking up in front. A scooped-out window in the front accommodated the expanding abdomen; a long jacket covered the window. Ads boasted that Page Boy’s skirts were “not wrap-around.” For the first time, maternity clothes resembled the latest Paris fashions. As Elsie was fond of saying: “You can’t hide the fact that you’re expecting a child… but you can detract from it.”

Page Boy also benefited from auspicious timing. Although ready-to-wear had been around for a century, at first only menswear and utilitarian clothing were mass-produced; fashionable ladies’ garments were the last to succumb to the industrial machine. By 1930, however, most women were buying their clothes from department stores or mail-order catalogues rather than having them custom-made. The baby boom and postwar prosperity transformed consumer buying power and spending habits, making the idea of clothes that would last just a few months palatable.

In 1940, on a family vacation to Los Angeles, Edna impulsively rented a storefront on Wilshire Boulevard, deeming it the perfect spot for Page Boy’s second boutique. On opening day, actress Margaret Sullavan bought an entire maternity wardrobe. It was the start of a beautiful friendship between Page Boy and Hollywood. Celebrity clients included Lucille Ball, Judy Garland, Debbie Reynolds, Princess Grace, and Mrs. Errol Flynn; Eva Marie Saint, nine months pregnant, accepted her 1955 Best Supporting Actress Oscar for On the Waterfront in a Page Boy-style skirt suit. Naturally, Page Boy used photos of these famous fans in promotional materials; true to their logo, the sisters were experts at blowing their own trumpet. By 1950, Page Boy’s “unexpected fashions for expectant ladies” were available in five boutiques and 350 department stores nationwide.

Page Boy offered maternity outfits for every occasion, from ski clothes to fur-trimmed dinner suits to lingerie. Originally geared to affluent and professional women, the company increasingly targeted small-town, stay-at-home moms as well. The patented cut-out skirt came with flat panels that could be sewed over the abdomen after giving birth, to extend the garment’s life (and appeal to customers who weren’t even pregnant). Dresses had hidden zippers to expand and contract the waistline—the original “during and after” garment. Ads highlighted the fact that Page Boy’s clothes were washable.

Courtesy of Specialties Photography in College Station

Changes in fashion in the 1960s hurt Page Boy more than the declining birthrate; trendy tent dresses and shifts could double as maternity wear. In response, Elsie declared “the cut-out skirt is dead” and designed skirts with stretch waistbands that could be worn with the short tops then in vogue. These skirts—which Elsie called “as simple as Mrs. John Kennedy’s”—could remain in use after the baby arrived. (Jackie Kennedy—a Page Boy client during her pregnancies—never appeared in the company’s publicity materials, a rare instance of discretion.)

The company rallied again in the 1980s, as a new generation of professional women spent lavishly on maternity wear, and fashion dictated power suits and tailored, preppy clothes that could not easily transition from everyday wardrobes to maternity. Page Boy offered a personal shopping service for busy working mothers-to-be and on-trend styles like bomber jackets and leather miniskirts—a first for the maternity market. The contemporary notion that pregnant women should show off their legs—because they can—originated with Page Boy. You can’t hide the fact that you’re expecting a child, but you can detract from it.

But these “pregnant yuppies,” as Elsie called them, wanted to wear familiar designer brands, not maternity-only brands. (By popular demand, Guess Jeans introduced a maternity line in 1985.) They also appreciated the convenience of buying maternity clothes, accessories, and baby things under the same roof—a move Page Boy resisted. At its peak, in 1984, the company had 30 boutiques across the country. But in 1994, the struggling company sold out to Destination Maternity.

The same concerns that made Page Boy a runaway success in the 1930s—cost, fit, changing styles and lifestyles—may doom maternity clothing today. With the sluggish economy and the increased emphasis on fashion—and fitness—at all stages of pregnancy, it’s no wonder that women are beginning to question whether maternity clothes are really necessary. It’s become a point of pride for a pregnant woman to wear her regular wardrobe as long as possible, as well as a point of comfort, physical and psychological. Would we recognize Kim Kardashian without her leather miniskirts, animal prints, and stripper heels? Would she recognize herself?

While even Kardashian gave into flats and tent dresses in her seventh month—a development that made headlines—it’s hardly unrealistic for pregnant women to expect to wear their pre-pregnancy clothes into the third trimester, with the help of a belly band or minor alterations. Doctors used to encourage eating for two; now, they closely monitor patients’ diets and weight. Prenatal Pilates and personal trainers ensure that women of means—the traditional consumers of upmarket maternity wear—stay fit throughout pregnancy, and slim down quickly after giving birth.

Cost, too, is an issue, even for celebrities. The Duchess of Cambridge—who regularly recycles her designer outfits—has only been spotted in a few maternity dresses, and they were from budget-friendly Topshop, ASOS, and Séraphine. The rest of the time, she has made do with her usual enviable wardrobe of wrap dresses, coat dresses, and shifts, perhaps with a button relocated here, a hemline adjusted there.

“We created a monster that came back to haunt us,” Elsie Frankfurt said of the tent dress. Today’s maternity industry has worked hard to convince customers that maternity clothes are fashionable and functional, offering maternity skinny jeans, maternity yoga gear, maternity bikinis, and more maternity cocktail dresses than a woman who can’t drink alcohol will ever need. Mall stores like Gap, H&M, and Ann Taylor Loft have added maternity collections that are virtually indistinguishable from their regular offerings. Even Spanx launched a maternity line in 2007. (While there’s always been a market for maternity support garments, these weren’t the maternity corsets of yore; Spanx explicitly targeted the thighs and butt, not the bump.)

At the same time, our everyday clothes have become more and more like maternity clothes. Stretchy fabrics are no longer reserved for swimsuits, just as custom-made clothing is no longer reserved for the wealthy, thanks to eShakti, Etsy, and the like. Maxi dresses, blazers, T-shirts, and leggings transition easily to maternity wear. There’s no excuse for looking like a beach ball in an unmade bed. If this trend continues, maternity clothes may be one less thing to expect when you’re expecting.

—

Dressing Modern Maternity: The Frankfurt Sisters of Dallas and the Page Boy Label by Kay Goldman. Texas Tech University Press.

See all the pieces in this month’s Slate Book Review.

Sign up for the Slate Book Review monthly newsletter.