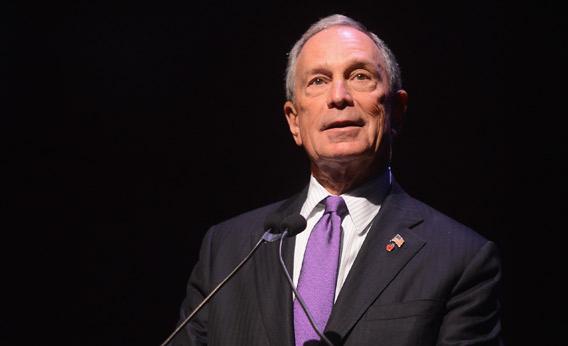

Last month, the New York City Board of Health approved Mayor Michael Bloomberg’s ban on the sale of sugary drinks larger than 16 ounces at restaurants and concession stands. Since its proposal in May, the restriction has been met with a PR campaign and a lawsuit by the American Beverage Association, head-shaking by a skeptical citizenry, and mocking glee by newspaper headline writers and Jon Stewart, who on his show said, “I think people look at this and say, ‘Well, that’s just silly.’ ”

Silly or not, the Board of Health voted 8-0 for the limited ban. The lone abstention, Dr. Sixto Caro, told the Associated Press he believes that to fight obesity the plan “is not comprehensive enough.”

Caro is wrong. The soda plan is perfectly incomprehensive. It’s so incomprehensive, it just might work. The array of similarly modest measures stitched together by Bloomberg over the last decade may represent the first new and effective government strategy of pursuing social justice in a generation.

For much of the 20th century, mayors ruled New York through audacious, sweeping measures. In the long wake of the New Deal, every mayor following Fiorello La Guardia inherited a mantle of urban renewal, the mandate to lift the poor and harmonize society’s economic and racial factions through immense infrastructure projects and dramatic growth in city services. La Guardia midwifed the radical idea that the city was responsible for its neediest citizens, and his successors, one by one, all stood for it and, because the dream was too big, ultimately failed.

No failure was more disappointing than that of John Lindsay, who entered office as a warm-hearted savior with matinee-idol looks. “New York is ill beyond belief,” Norman Mailer wrote in his endorsement of Lindsay in 1965. “I think he’s a great guy, and it would be a miracle [if] this town had a man for mayor who was okay.” Yet Lindsay’s two terms would be marked by nearly ceaseless strife: major transit and sanitation strikes, increased racial tension, looming deficits. The conflict between families trying to make their own way and a system intent to carry everyone into a world of tomorrow had sharpened to a dangerous point. The city was rapidly losing its taste for grand ambition.

The darkest of New York’s days came once Lindsay left office, in the four-year pit presided over by the hapless Abe Beame, when the city came within mere hours of bankruptcy, and looting and arson in the ’77 blackout burned parts of Brooklyn nearly off the map.

The only way to go, in hindsight, was up—thanks in large part to the rise of Wall Street, which paid, directly and indirectly, for much of the city’s resurgence. Ed Koch, David Dinkins, and Rudy Giuliani finished out the 20th century as the first caretaker mayors of a post-industrial New York, each attempting to build a city hall independent of party machines, power brokers, and ceaseless patronage (with varying success). That they proved the city was even capable of being managed—hardly a credible idea for decades—cemented their place in history. No surprise that social programs were de-emphasized in these years; there were more pressing things to worry about. At least Koch worked to functionalize and clean up existing anti-poverty programs. Under Giuliani, welfare caseloads declined more than 50 percent and food-stamp enrollment dropped off precipitously. La Guardia’s New York was by now little more than a faint memory.

No one would have blinked in 2002 if the city and its new mayor had continued this steady sloughing of the social safety net. Indeed, Bloomberg retained many of Giuliani’s work-requirement welfare reforms. He could also have done nothing, resting on his first-term laurels as a master of the budget, having headed off a post-Sept. 11 deficit crisis. But what the Bloomberg administration did instead was formulate, within the constraints of its era, a new way to address the effects of unequal living—and in terms of the most pressing issue of today: health care.

There can be no ambiguity about the progressive nature of Bloomberg’s long, unprecedented war on smoking and obesity: It is aimed squarely at the city’s poor. Uncertainty about this exists only because the agenda has passed in a spread-out package of citywide initiatives over a decade, each one just small enough—just un-ambitious enough—to be mocked as silly and then adjusted to by residents, and later imitated around the country, without smelling of “welfare.” The public face of the agenda, in fact, has been about taking away, in the form of bans and restrictions, rather than handing out. See: the two major smoking bans (bars in 2002, parks in 2011); the 2005 phase-out of trans fats; the 2008 requirement of restaurants to display calorie counts. While these “draconian” restrictions drew attention and protest, other city programs—such as expanded food stamps, diet education, quitting-smoking assistance, even coupons for farmers markets—have thrived in complement with their higher-profile cousins.

This brings us back to the soda ban. What was forgotten in the summer’s fizzy furor is that the soda ban exists only because the Department of Agriculture denied (perhaps smartly, given the trend against overt demographic targeting) a 2010 request by Bloomberg for a trial run forbidding food stamps from being spent on soda in NYC. (It should be noted Bloomberg also argued for a state soda tax and lost, as did Gov. David Paterson before him.)

So the ban we ended up with is actually a refashioned version of an initiative meant expressly for the city’s poor—who are also the city’s most obese. To many, this final version of the soda ban is loophole-ridden and unconvincing as a health measure. Yet the ban was never meant to be a catch-all. Next March, when the rules take effect, you will still be able to walk out of Wendy’s with two max-size 16-ounce drinks instead of a 32-ouncer, or lug as many 2-liter bottles out of the corner store as you can carry. There have been no pro-smoking riots. The personal sacrifice imposed by these measures is certainly tiny compared to the neighborhood-bulldozing futurism of post-war New York, and more tolerable than a complete prohibition of sugar and cigarettes. They are akin to Richard Thaler and Cass Sunstein’s “nudges,” concerned primarily with resetting the default option—to borrow the language of behavioral economics—available to people as they go about their day. Residents bumping about the public sphere (and in New York, it’s basically all public sphere) have slowly been encouraged to adapt to a new normal: Not only are bars and parks now smoke-free, but smokers who spend time in bars and parks are buying fewer cigarettes; customers who notice calorie counts are more likely to order less; and now inveterate soda drinkers who normally consume by the quart may soon discover a pint will do just fine.

In other words, it’s a lot of little. And all of it is aimed at getting results from those who can’t afford organic or a gym membership. (All eyes are on one borough in particular: the Bronx, which has the highest smoking rate and the highest obesity rate. When was the last time you saw a Park Avenue doyenne sipping a Big Gulp?) At a public hearing in June, City Council member David Greenfield found fault in the methodology, asking, “Why are you taking this piecemeal approach which may or may not work, which you don’t necessarily even have the science to back up?”

Yet piecemeal is a good thing these days. And what’s most notable is that the Bloomberg administration has been leading on this movement instead of following. Thaler and Sunstein’s book only came out in 2008 (and they might categorize Bloomberg’s regulatory moves as pushing the envelope of nudging), and Sunstein brought his scholarship to the White House starting in 2009. Philadelphia and California passed trans fat bans after New York, in 2007 and 2008. The next era of social justice is developing into a tightrope walk between individual freedom and managed environment, rather than swinging wildly between them—the natural offspring of the 20th century’s great ideological clash. And it’s happening here first, in a city of 8 million, rather than a frontier town. Where better?

As for the backing of science, when the success of the soda ban is gauged starting next year (three new studies—published after the Board of Health’s vote—provide advance support), Bloomberg will know he’s already winning in perhaps the single most important metric: New Yorkers are living longer—faster—than anyone else in the country. In 1990, according to the University of Washington, Big Apple residents lived three years shorter than the average American. Since then, they have added eight years to their lifespan, while the national average increased at only a rate of 1.7 years per decade. The study’s real kicker? The turnaround is not due solely to reduced crime:

More than 60% of the increase in life expectancy since 2000 can be attributed to reductions in heart disease, cancer, diabetes, and stroke. In the past decade, death rates for heart disease alone fell by some 25%.

The soda ban and its relatives are not anti-poverty programs as traditionally defined, but their place in the fabric of modern social policy can no longer be denied. Forgive Mike Bloomberg for still believing that his legacy still relies on being the education mayor, a goal he has put tremendous resources into with—alert—audacious breadth and pace, yet yielding inconclusive results. New York health commissioner Thomas Farley knows better: Bloomberg is “the world’s first public health mayor.”