It may have gone under the radar in the United States, but one of the most lucrative television deals in the history of professional sports was signed this summer. In June, Rupert Murdoch’s British Sky Broadcasting and British telecom giant BT collectively bid £3 billion, or $4.7 billion, for the rights to broadcast English soccer in the United Kingdom for the next three years.

On a yearly basis, major American networks pay just twice as much to broadcast the NFL in a country that is five times as big. And after the Premier League negotiates international broadcasting rights over the next few months, it should come close to closing the remaining gap. England’s Premier League is now the most profitable soccer league in the world, and one of the most successful sports businesses of any kind.

The Premier League’s economic success is a surprising story, the result of a remarkable and unexpected turnaround. In 1992, when the top flight of English soccer split off from the Football Association’s lower leagues after a contentious contract dispute, English soccer was as much of a national embarrassment as it was a national pastime. By the early 1990s, soccer in England had squandered a century-old history as the most storied sports competition in the world.

English teams were coming off a 10-year stretch that saw their reputations sink to catastrophic levels both domestically and internationally. In 1985, soccer reached its nadir in the country that invented the sport. Thirty-nine fans of the Italian club Juventus were killed by a collapsing concrete wall at Heysel Stadium during a European Cup match in Belgium following clashes instigated by supporters of Liverpool. After Heysel, English clubs were banned from competing in Europe indefinitely, a suspension that ended up lasting five seasons. That same year also saw one of the worst soccer riots in history between supporters of Millwall and Luton back in the U.K.

In addition to historic bouts of hooliganism, British soccer had to contend with dangerously deteriorating stadiums from the Victorian era. Just weeks before the tragic events at Heysel and just two months after the Millwall-Luton clashes, a horrific stadium fire at Bradford City resulted in 56 deaths.

By the end of the 1980s, English soccer was defined not by the achievements of the players, but by the violent reputations of the game’s fans and by stadium disasters. Margaret Thatcher’s government, notoriously antagonistic to the traditionally working-class sport, had started to treat soccer as a law-and-order issue and was clamoring for legislation that would require fans to show identification cards in order to attend games.

On April 15, 1989 the sport hit a new low point at an FA Cup semifinal between Liverpool and Nottingham Forrest at Hillsborough Stadium. Because of traffic jams on the road from Liverpool to Sheffield, streams of Liverpool fans arrived late to the game. Hillsborough Stadium did not have enough stewards to manage the rush of fans. Thousands of Liverpool supporters were hurried though gates into overcrowded standing-room terraces that were then typical of English football stadiums. Once those terraces were well beyond capacity, the fans were sent into holding “pens.” The pens quickly became dangerously packed as the rush of fans continued.

Eventually, protective barriers between the fans gave way and scores of people were pressed against each other, causing a fatal “crush.” Ninety-six people lost their lives, many dying from asphyxiation.

Top police and political officials attempted to scapegoat Liverpool supporters. Rupert Murdoch’s tabloid the Sun, citing false reports from anonymous sources in the South Yorkshire Police force and Parliament, claimed that Liverpool fans had robbed the dead, urinated on them, and prevented police and emergency services from doing their jobs.

“Initially, when all the Liverpool fans were blamed for having caused this there was a credibility to that because of the decade we had,” says Ian Ridley, author of There’s a Golden Sky: How Twenty Years of the Premier League has Changed Football Forever.

(Only last week did the full truth come out, when the findings of a three-year long inquest into the Hillsborough tragedy were released. Not only did it definitively conclude that Liverpool supporters were not responsible for the deaths, it blamed the police for attempting to cover up their own faults by altering 146 police statements after the fact. Most disturbingly, police covered up the fact that some 41 lives could have been saved had the emergency response been swifter. In a speech before Parliament, Britain’s Prime Minister David Cameron apologized to the family members of the Hillsborough victims.)

In the early 1990s, the Hillsborough tragedy came to be seen as the culmination of a disastrous era for the sport. “Hillsborough was almost the logical conclusion of that whole decade when it came to football,” Ridley told me. “Football was on its knees basically.”

Out of this darkness, English soccer could have gone in one of two directions. The political class could have accepted the false narrative of Hillsborough as proof that England’s soccer fans were hopeless and that the sport was beyond salvation. The government could have gone full-steam ahead with Thatcher’s ID law. This would have alienated the sport’s existing fan base, while reinforcing the stigma that soccer was a sport for poor, drunken thugs.

But instead, three things happened that changed the course of English soccer—and ultimately the international sporting order—forever.

First, the government commissioned Lord Peter Taylor to conduct the initial inquiry into the cause of the Hillsborough disaster. Though he didn’t reach the sweeping conclusions of police ineptitude and conspiracy that this month’s report revealed, Taylor did determine that Liverpool fans were not at fault. The lax crowd-control methods of the police and poor stadium conditions were cited as the reasons for the catastrophe, and Taylor listed several recommended correctives. Principally, he advised that England’s major stadiums be converted to “all-seater” facilities, with the removal of standing-room terraces. This recommendation was implemented by the top two divisions of English football over the course of the next 10 years.

“Lord Justice Taylor is one of the great unsung heroes of English football and society in general,” Ridley said. “All his recommendations on seating, while they were expensive, they certainly paved the way for a new mood around football whereby fans were no longer herded like cattle.”

The move away from terraces had the unfortunate effect of pricing poorer fans out of stadiums. But it’s difficult to quibble with the safety results—there have not been any deaths as the result of soccer stadium conditions in the United Kingdom since the Taylor recommendations were implemented, and incidences of hooliganism have decreased significantly.

The second change in the wake of Hillsborough had to do with the actual product of English soccer on the field. At the 1990 World Cup in Italy, England’s early matches were marred by the typical rioting, arrests, and deportations of English fans, as well as a slow start to the tournament by a team that barely eked into the second round.

“There was a bad taste about football in England, a horrible taste,” Paul Parker, a starting defender on the 1990 England team, told me during an interview two years ago. “People didn’t want to be involved in it,” he added, recalling the standing of the sport heading into the 1990 World Cup.

But the knockout phase of the competition produced some of the greatest sporting drama the nation had ever seen. First, David Platt scored a stunning volley in the 119th minute of the team’s opening knockout match to claim a 1-0 victory for England over Belgium at the last possible moment of extra time. Then England repeated this seemingly miraculous performance with a shocking come-from-behind 3-2 win over Cameroon. Again, the decisive goal came in a thrilling period of extra time.

England ultimately lost the semifinal match with arch-rivals Germany in a penalty shootout, but it remains one of the most memorable soccer games the nation has ever played. The team was also rewarded with the fair-play trophy for its record of sportsmanship, a fact that Parker believed gave an added shine to the achievement.

The squad returned home conquering heroes rather than social pariahs. A flock of 250,000 jubilant fans greeted their arrival. “It looked like the Beatles were being knighted when we turned up at the airport,” Parker remembered.

“There was a wave of optimism and euphoria,” author Ian Ridley told me. “I don’t think we were fooled that English football was in great shape, [but] it allowed people to cast off a bit of the gloom and create a bit more of a climate where people thought, ‘well, how do we capitalize on this improvement?’ ”

All of this led to the final, and perhaps most critical step in the nation’s soccer revival: The creation of the Premier League in 1992. Just a few months after the end of the World Cup, the heads of the five biggest English clubs met with the director of ITV’s sports coverage to map a new course for the sport. For decades the top league had shared broadcasting revenue and negotiated rights jointly with the country’s lower divisions, the equivalent of the sport’s minor leagues.

The six men decided that this arrangement was not working. The big-five club owners would pressure the rest of the English first division into pulling out of the existing league system and for the first time ever negotiating its own TV deal. The lower leagues were ultimately forced to go along, and the new Premier League was forged. That first deal was signed for a then-record £300 million over five years with Rupert Murdoch’s fledgling satellite provider Sky winning the bulk of the rights. The 1990 World Cup team and the founding of the Premier League two years later led to an immediate image revival for English soccer, at least from a corporate standpoint.

“People who weren’t football fans, started recognizing footballers,” Parker recalled. “Major companies started wanting to be involved in football again.”

After the injection of fresh money into the top-tier of the sport and the stadium changes initiated by the Taylor report, the league started to see an expanded fan base. As matches became safer and stadiums became cleaner, attending games became a normal family activity.

At the same time, foreign players began to take a greater interest in the English game because of all the new money. In the 1980s, foreign players who left home had opted to play in the more prestigious Italian league Serie A. By the mid-’90s, they were starting to come to the cash-rich Premier League.

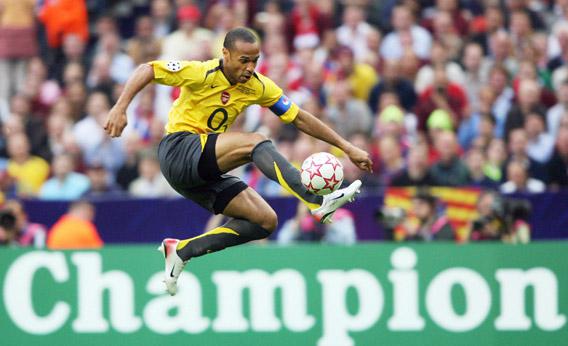

The European continent’s biggest stars—Eric Cantona, Jürgen Klinsmann, Dennis Bergkamp, Thierry Henry—who in the earlier era likely would have opted to play in Italy, were instead coming to England. The influx of foreign players and managers have radically improved the dreary, rainy soccer of the ’70s and ’80s, famously described by Nick Hornby in Fever Pitch. The Premier League is now as exciting as it is wealthy. Today, a Spurs-Arsenal match featuring such international stars as Gervinho, Lukas Podolski, and Emmanuel Adebayor is more likely to see seven sizzling goals than none.

As the product improved on the pitch and more money came in, the foreign TV markets began to take an interest. The domestic TV deals, meanwhile, continued to swell. In 1997, Sky renewed its deal for £670 million, a 337 percent increase in annual rights. At the same time that the satellite station was drawing in millions of new subscribers, the country’s soccer clubs were now drawing the largest share of their revenues from the TV deals.

The upcoming round of international TV contracts are expected to amass as much as £2 billion, which—when added with June’s record domestic deal—would move the league within striking distance of the NFL for the wealthiest in the world. The whole endeavor weathered the latest economic crises, with player wages increasing commensurately with TV rights.

“Football has done very well during an economic recession because it remains a comparatively cheap form of entertainment,” Ridley said.

At the same time, however, record sums of money have resulted in a disparity on the field and in the stands. Tickets in all-seater stadiums are more expensive than they were in the terrace days, while clubs have moved more towards the American model of aggressively marketing season tickets. Ticket prices have increased by upward of 1,100 percent since 1992.

Foreign owners, meanwhile, have bought some of the top teams for exorbitant sums, and started paying salaries that are inconceivable for smaller market clubs. This has led to the creation of a handful of wealthy superteams that dominate the competition year in and year out. At the beginning of any given season, it’s fairly easy to know which two or three major teams are going to contest for the title by year’s end.

Despite the league’s self-image crisis, it still is more competitive than the other big European league in Spain, where just two teams inevitably dominate year after year. It’s also very difficult to argue with the bottom line. The sport continues to generate billions of pounds in TV, merchandising, and ticket revenues, and a cool £1 billion alone in tax revenues for the British government.

Longtime fans might resent the idea of a billionaire Russian owner, billionaire American owners, and a billionaire Sheikh from Abu Dhabi having “bought” the last three English titles for Chelsea, Manchester United, and Manchester City respectively. But in terms of pure sporting spectacle, last season was probably the most dramatic finish any European soccer league has witnessed, ever. In the final minutes of the final day of the season, Manchester City clinched their first title in 44 years ahead of cross-town rivals Manchester United. City was able to capture the trophy only after Bosnian star Edin Dzeko and Argentine star Sergio Aguero both scored goals in injury time to lead the club to a shocking 3-2 come-from-behind victory over London’s Queens Park Rangers.

Just one thought came to mind after last year’s dramatic finale: What a comeback.