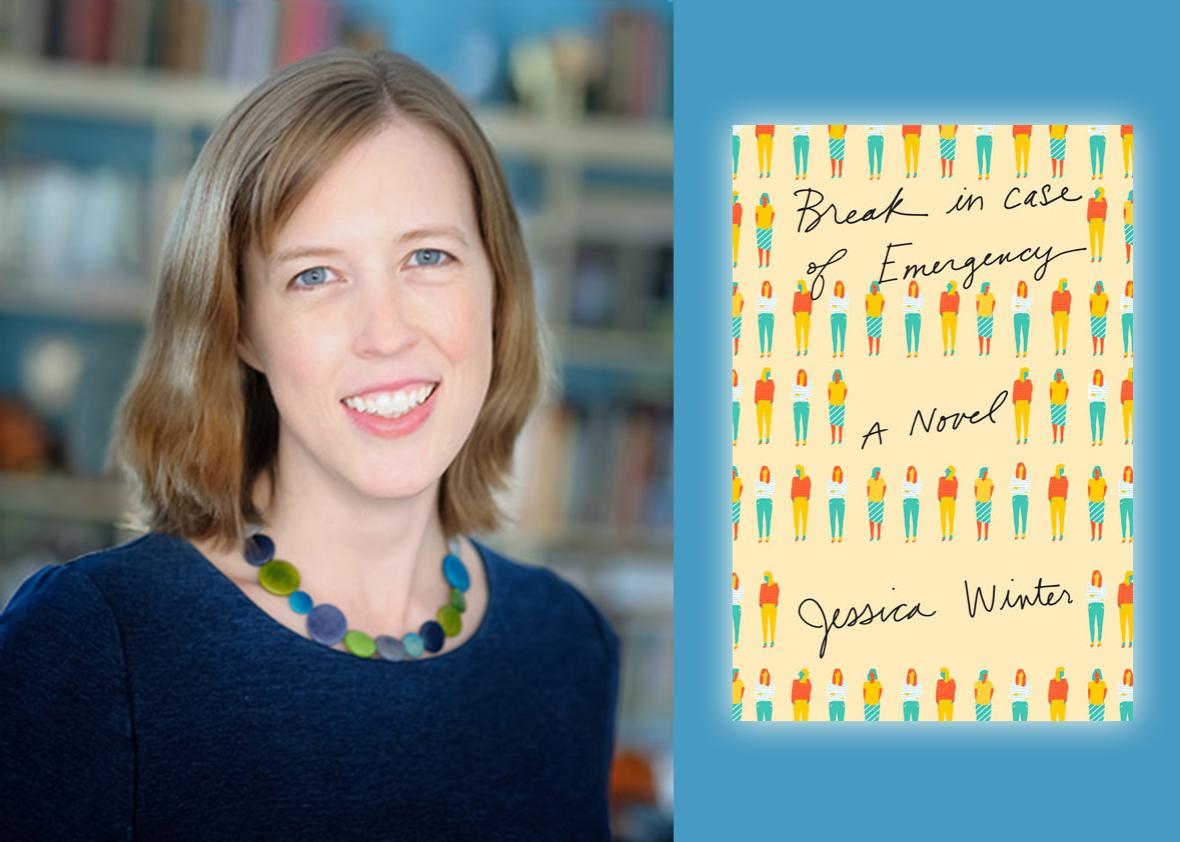

Jessica Winter is Slate’s features editor and the author of the new novel Break in Case of Emergency, which has been aptly characterized as a workplace satire (although it is much more than that). The novel’s protagonist, Jen, takes a job at a mushy “women’s empowerment” nonprofit founded by a wealthy former TV star. The foundation has too much money and not enough for its employees to do. Jen sits through meetings in which the staff talk endlessly without saying anything, writes countless memos for her impossible-to-please boss, and Gchats with her unflappable co-worker Daisy. Anyone who has ever had an intolerable office job will probably see him- or herself in Break in Case of Emergency—which might be painful if the book weren’t so funny.

Jessica and I have worked together for more than three years, and she’s now my manager. Since I write about workplace issues, I wanted to know more about how and why she conjured such a farcically noxious workplace in Break in Case of Emergency and what lessons white-collar office drones can draw from the book. We chatted last week about the differences between female and male managers, the importance of not caring too much about being liked, and the Dear Prudence column that inspired part of the book. –L.V. Anderson

L.V. Anderson: You and I happen to work together in a workplace that, I am happy to say, is pretty functional, so I know Break in Case of Emergency isn’t a roman à clef about Slate. Why did you want to set your book in a dysfunctional hellscape of an office?

Jessica Winter: A dysfunctional workplace is always going to be a maelstrom of fascinating human phenotypes and behavior disorders, and it seemed like a fun place for a novel to muck around in. I was specifically interested in an all-female version of a toxic workplace, especially one obsessed with “empowerment.” And in a bigger sense, I wanted to look at how a toxic job can work its poison into other areas of your life: your romantic partnerships, your friendships, your health, your sense of self.

Anderson: That is such a good point about a toxic job being poison. When you’re unhappy at work, it’s pretty much impossible to be happy in general. Do you think that’s just because people who work full-time spend so much time at work, or is there something fundamental about work that gives it enormous influence over your sense of well-being?

Winter: It’s both, but it’s especially the latter. If your job is one that’s fulfilling, creatively satisfying, one that brings you into daily contact with people who value and support you and who are just fun to be around, it buoys you in general, but at the same time, it’s not something you dwell on—it’s not like you go home at night to your dog or your kids or your books and think, “Wow, what a great job I have.” I mean, maybe once in a while you do, but mostly you take it for granted, in the best possible sense. Whereas if you have a bad job—and let’s add a blanket caveat here that in this situation we are talking about demoralizing white-collar office jobs, which would strike many, many people across America and around the world as extremely good jobs indeed—you dwell on it, you obsess over slights, you lay awake at night thinking about how you can get your superior to respect you or how to get a colleague to pull her weight, and those worries and resentments can wrap their tentacles around every area of your life. It’s very hard not to internalize this stuff, where you feel yourself becoming a synonym or synecdoche for your job: “I have a shitty job, ergo I am a shitty person.”

I once had a boss who was such a micromanager and so unstable and so bizarrely obsessed with me and whatever I might be doing wrong at any given moment that I devised a physical ritual around her. Whenever she sent me an email, I would literally push myself away from my desk and read the email from a squinting distance. It was a physical act that declared, “She cannot get to me; I am not internalizing this.” I thought it was so clever and healthy at the time, and now I’m just appalled at myself. Also, the trick didn’t even work, because usually about the time I’d push my chair away she’d be coming up behind me barking, “DID YOU GET MY EMAIL.”

Anderson: That ritual does actually sound healthy to me—a way of keeping things in perspective. People are capable of putting up with a lot of bullshit in order to survive at work, and later on, once they’ve extricated themselves from the situation, they’re shocked by how bad it was.

I want to get back to your earlier point about “an all-female version of a toxic workplace.” I think the politically correct position is that that the vast majority of female bosses aren’t territorial mean girls and that women are no less supportive of one another in the workplace than men are. (See, for instance, Sheryl Sandberg on “the myth of the catty woman.”) This is a tricky topic, but do you think that bad female bosses are bad in a particularly female way or that female-dominated workplaces are dysfunctional in a particularly female way? (With the caveat that we’re talking about learned behaviors: the way women are socialized not to be too direct, not to ask for too much, etc.)

Winter: We are wading into some dangerous territory, but then again, so does the book. Obviously, any workplace that doesn’t attain some threshold of hybrid vigor in terms of all kinds of diversity—gender, race, sexual orientation, socioeconomic status—is probably going to be inferior to those that do. Having said that, I have no doubt that there are certain all-female workplaces that are feminist paradises. But is there a specific terribleness to the terrible all-female workplace? I am going to venture—very hesitantly and with the full understanding that I may be forfeiting all my feminist credentials—that yes, there is. And that specific terribleness has a lot to do with, as you say, how women are conditioned not to be too direct or ask for too much or put themselves forward. The alchemy of a bad workplace can transform those traits into cattiness and back biting and virulent passive aggression, which I guess is the mirror image of the plain old aggression aggression you might get in a male-dominated workplace.

Anderson: I’ve avoided writing about ways that management styles can be gendered because I think it’s a very tough tightrope to walk. But if I were the feminist-credential fairy, I would wholeheartedly let you keep your credentials.

There’s an interesting contrast in that the book’s protagonist, Jen, keeps trying to hit the moving targets her passive-aggressive boss puts in front of her. Meanwhile, her cube mate, Daisy, just does not give a fuck about work. Daisy is a very funny character and a source of comic relief in scenes that might otherwise be overly infuriating, but is there any other reason you wanted to show these two very different approaches to working in a dysfunctional office?

Winter: Daisy knows her stuff, and someday she is going to be running Doctors Without Borders or the Red Cross or some legit organization that makes a real difference in the world. But for whatever reason she is temporarily in the middle of this celebrity-foundation shit show, and she’s making the best of it where she can, and where she can’t, she plays Socialist Revolution on Facebook (the book is set in 2009, when people still played games on Facebook) or steals out to movies in the middle of the day. This job is a blip in her life’s trajectory, not a referendum on her existence. And Jen is constitutionally incapable of letting go in that way. Jen wants to fix what is unfixable, and in this regard, she is very dumb and Daisy is very smart.

I wanted Daisy to be almost a fantasy character, the absolute ideal of a co-worker—the colleague you dream about having. Everyone who read early drafts of the book wanted more Daisy, and I said, “No, I need you to feel an unrequited longing for Daisy.”

Anderson: So does this mean you think it’s not actually possible for a real person to detach from a horrible work situation as well as Daisy does?

Winter: I think there’s a force field that certain people can generate in bad workplace situations—a kind of calm competence that is wholly uncoupled from any concern about being liked or approved of—that creates a barrier between you and the situation that you’re in. I don’t think you have to be a superhero to achieve that, but it helps.

Anderson: You need a robust sense of self, so you don’t automatically go to those thoughts of “I have a shitty job, ergo I am a shitty person.”

Winter: Yes. Jen’s sense of self is deeply imprinted and shaped by other people’s perceptions or what she perceives of them. That is true of anyone—only a psychopath 100 percent wouldn’t care about other people’s opinions—but it’s overly and painfully true of her, and that’s why she is doomed in a toxic workplace.

Anderson: Jen undergoes treatments at a fertility clinic. Her boss, Karina, asks her lots of invasive questions about why she’s late to work. What do you think people should say when their bosses ask them personal medical questions that they don’t want to answer?

Anderson: Well, I do wish you’d stop following up every email by coming up to my desk to ask, “DID YOU GET MY EMAIL.” And I’m a little miffed that you have created a fictional co-worker who is better than my actual co-workers, which makes me wish my actual co-workers would step up their game.

Anderson: Huzzah.

Winter: Should I ask you what is the worst thing about me as a “manager”? My most Karina-like trait?