Last month, millions of college seniors received their diplomas, threw their mortarboards in the air, and set out to find a job. If you are among them, I don’t envy you. Trying to get your first job out of college is a soul-crushing experience. When you don’t have much (or any) job experience, you have very little leverage in job negotiations other than your willingness to work cheaply. You are also, by virtue of your age, likely to be judged by hiring managers as immature, careless, and unprofessional.

To counter this, many young job-seekers become anxious perfectionists. They scour their cover letters and résumés for typos and grammatical errors. They obsess over the wording and punctuation of every email. They can probably relate to a job hunter who wrote what might be the saddest letter I’ve ever read in an advice column. Seeking advice from Ask a Manager columnist Alison Green in 2009, this tragic figure wrote:

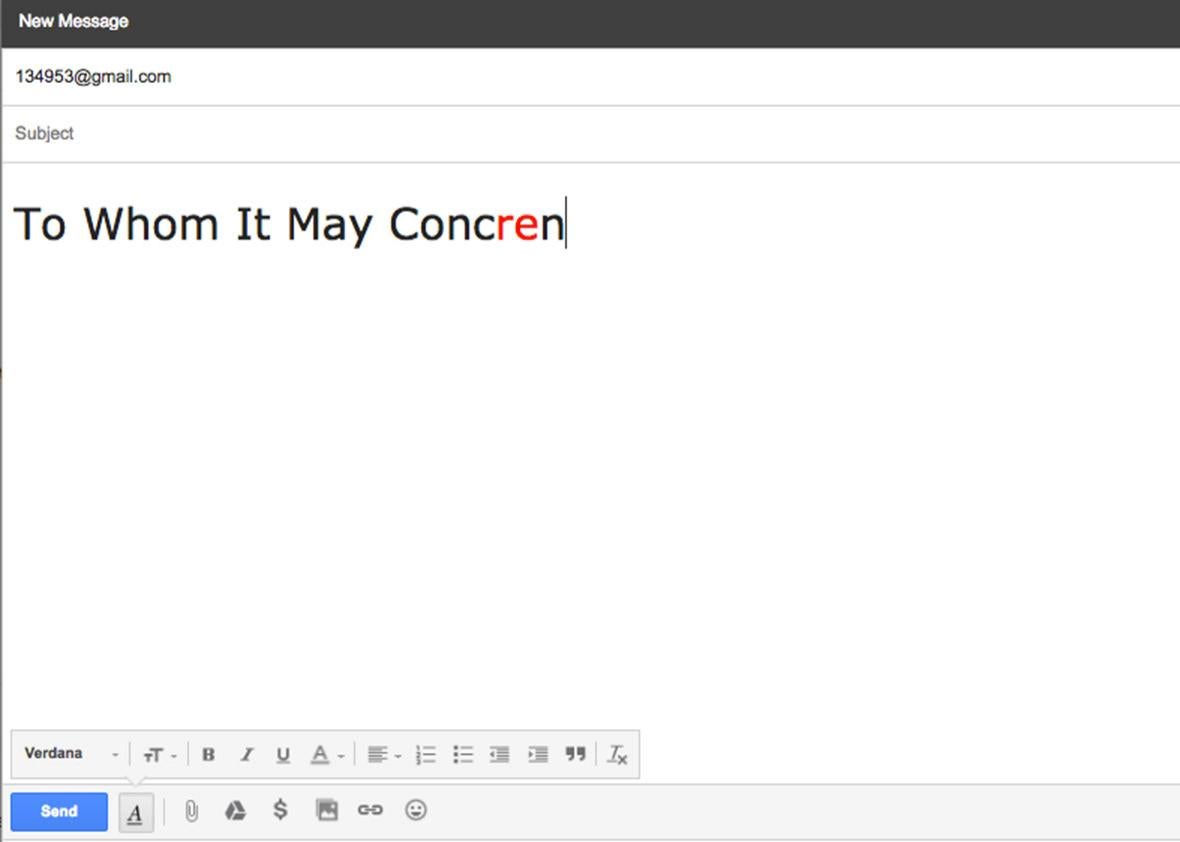

I just made the worst mistake ever and I feel so sick about it. I found a job that I really want. I spent two days drafting my cover letter and adjusting my resume for this position. … I wrote a short little email attached my letter and resume and then hit send.

Once I hit that send button, I saw a typo. I guess in my excitement to get my resume sent, I re-read the email too fast. So unlike me. When I saw the typo it seriously took my breath away. I frantically looked for a cancel button, but there isn’t one.

If you are a recent college grad and you pride yourself on your writing, you probably see yourself reflected in the letter writer’s obsessive attention to detail and wince at the feeling of being undone by a stray keystroke.

I have good news for young, typo-averse job seekers: It gets better. As you advance in your career, you won’t have to care about making every sentence that you type absolutely perfect anymore, and it will be a huge relief.

In my first few years out of college, I was a stickler for grammar, spelling, and punctuation in my work correspondence. I proofread every email and deliberated over every semicolon. I remember being surprised and slightly alarmed when I began working with older, well-established, even semi-famous writers and editors who didn’t seem to give a damn about whether they capitalized proper nouns, used commas consistently, or accidentally typed teh instead of the in emails. I was concerned for them. Didn’t they worry about how they came across?

Now I know the answer: No, they didn’t worry about how they came across. They were emailing an entry-level underling; why would they care whether I thought less of them for not proofreading their emails?

Those emails were my introduction to the subtle power cues embedded in workplace correspondence. At best, informal, typo-ridden messages sent from the top of a professional hierarchy to the bottom reflect the fact that bosses aren’t particularly concerned about coming across as sloppy to their subordinates. At worst, they’re a deliberate power move—a signal to junior staffers that they aren’t worth the time it would take to correct the mistakes in an email before hitting send. Either way, the presence or absence of typos in an email—along with how polished and formal it seems—can usually tell you a great deal about the power dynamics between sender and recipient.

The relationship between sloppiness and authority has been well-documented since the dawn of office email. One of the earliest academic studies of the implicit messages contained in office email describes the president of a company replying to a formal, multiparagraph email from a junior staffer with two mostly uncapitalized sentences including, “one would think with an mis dept there they could to their own training.” (Misspelling a two-letter word is the ultimate power move.) A later study of emails sent within an academic department noted that “email text … written by staff at the lower ranks (e.g. secretaries and support staff) often appears structured and formal … The messages by professorial staff … appear short, to the point, and spontaneous.” (“Spontaneous” is a polite euphemism for “sloppy.”)

Luckily, you don’t have to be a master of industry or a power-hungry jerk to loosen up about email—you just have to earn a reputation among your associates as a capable worker. Being able to mistype with relative impunity is one of the underrated perks of demonstrating basic competence in your job: The more you have a reputation for being reliable and doing good work, the less your reputation hinges on whether you make every email succinct and polished. And if you know you won’t suffer professionally if you make an occasional typo—or just phrase something clumsily—why on Earth would you take the time to run a magnifying glass over every email before you send it?

This doesn’t mean that you, recent graduate, don’t need to proofread every email. Alas, you do need to proofread every email. It’s very possible that you will be harshly judged if you send a cover letter or a résumé with an error or an ungainly sentence in it, because the person reading your application materials knows nothing about you except that you don’t know how to spell committed or how to avoid the passive voice when it isn’t necessary. It isn’t fair that you will be punished for small mistakes when more senior people in your field are not. After all, everyone makes typos and uses awkward phrases sometimes, regardless of how smart and skilled they are, and no one deserves to be judged by their worst moments. But this is how it works, fair or not.

And so, if you’re a young professional, it makes sense to keep your work communications clear and grammatical even when your bosses don’t. But someday, a few years from now, you will reap the benefits of working hard and building your professional reputation when you send a work email with a typo in it, and you just don’t care, both because you know your work stands for itself and because you’re comfortable enough in your skin not to beat yourself up for your mistakes. It’s hard for me to explain to a young, uptight grammar fanatic just how great this feels.

If you’re a young, uptight grammar fanatic, you might be horrified to think that you might someday stop caring about the correctness of your emails. Who would you be if you stopped being a pedant? I’ll tell you who you’d be: You’d be someone whose identity is built on your accomplishments and competence in your chosen field rather than on the absence of small mistakes.

I’m not saying you’ll never need to care about the neatness and precision of your digital work communications again. Unfortunately, research indicates that people of color are judged more harshly for their typos than white people—yet another way in which minorities have to work harder for the same recognition. Most managers and executives have bosses or clients to whom they must present their best digital face. And every time you apply for or start a new job, the cycle starts over again: You, in your position of relative inexperience and powerlessness, must again attend to your email hygiene as you observe the norms of your new office, just as you’ll probably dress up for your job interview and your first few weeks of work while you figure out the dress code. But you will never have to care as much about making your work emails perfect as you do in your search for your first job. For now, proofread carefully, and know that it gets better.