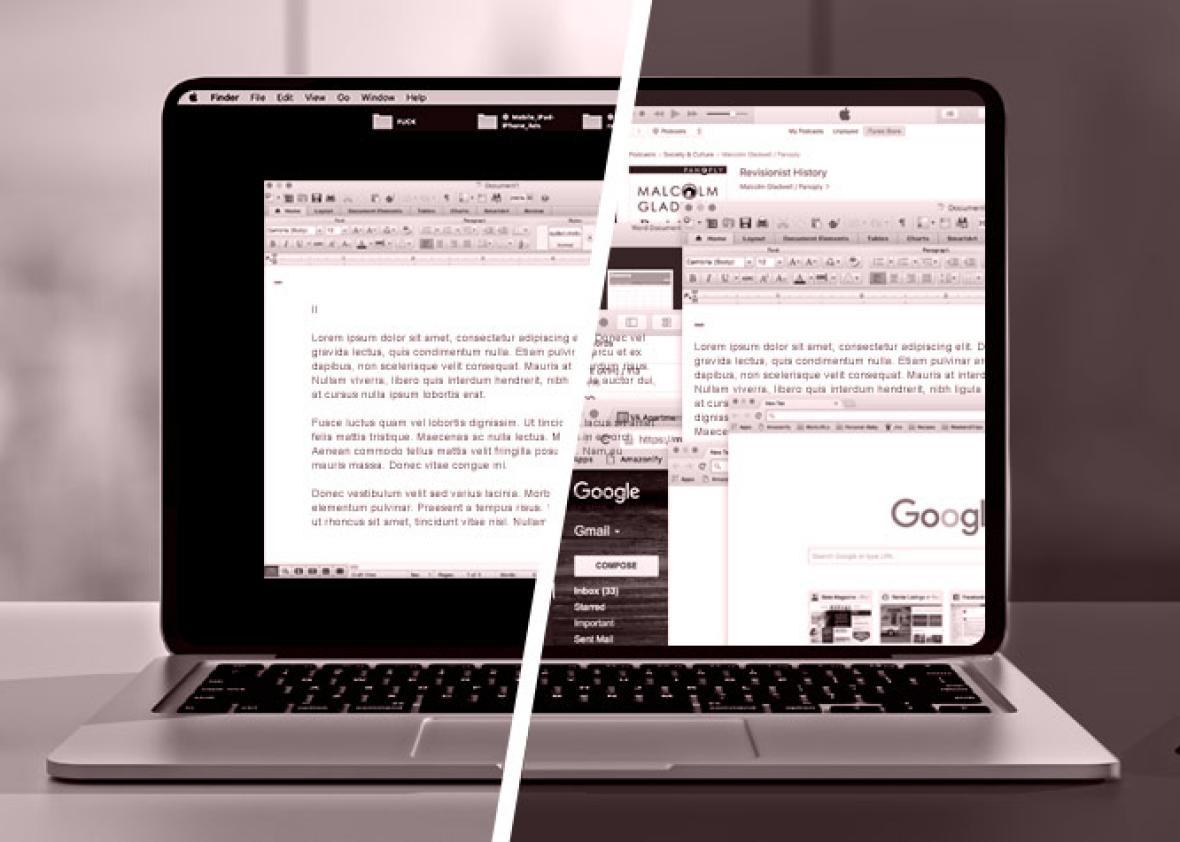

I am a champion multitasker at the office. I attach my laptop to a second monitor, which allows me to have at least two applications open and visible at all times. I toggle between Word and Slack or Outlook so I can stay on top of new messages while I’m writing or editing. My Chrome window contains at least half a dozen tabs containing Gmail, Twitter, Slate traffic reports, and a handful of partially read articles that I will, eventually, return to. In meetings, I skim Slack and Twitter while half-listening to things that don’t concern me directly. In short, you will never find me doing just one thing at a time. (That’s not even to mention the epic multitasking I do outside of the office: filling in crosswords while listening to podcasts on the subway, listening to music while riding my bike, playing Words With Friends while watching soccer …)

According to experts, all this multitasking is rotting my brain and diminishing my productivity. A series of experiments at Stanford showed that people who regularly multitask are a lot worse at basic tests of spatial perception, memory, and selective attention than people who don’t. Students who try to multitask while doing homework “understand and remember less, and they have greater difficulty transferring their learning to new contexts,” reported Annie Murphy Paul in Slate in 2013. People who multitask even have lower levels of gray matter than people who stay focused (although the relationship isn’t necessarily causal).

I vaguely knew all this, but I was in denial about how pervasive my multitasking had become. It didn’t hit me how long it had been since I had focused on just one thing for a sustained period until I read a recent essay in the New York Times Sunday Styles section with the provocative headline, “Read This Story Without Distraction (Can You?)” (I could not.) Writer Verena von Pfetten’s thorough summary of the case against multitasking made me ashamed of my distraction habit. “[M]onotasking is a 21st-century term for what your high school English teacher probably just called ‘paying attention,’ ” von Pfetten writes. Had my habits really gotten so bad that I was no longer capable of paying attention?

I decided to do an experiment to find out. For one week, I would do exactly one thing at a time at the office: no responding to emails while editing stories, no checking Twitter while in the middle of reading an article, no looking at text messages while writing a blog post. I would do things sequentially instead of simultaneously and see if it affected my productivity, my energy, and my mood. (I allowed myself one exemption, deciding it was OK to continue eating breakfast and lunch at my desk. After all, consuming calories isn’t exactly an intellectual activity. Mindful eating advocates, send your scolding to theladder@slate.com.)

On starting this personal experiment, I discovered that monotasking required a lot of mindfulness, in the sense of being conscious of and deliberate about what I was doing at any given time, instead of allowing my mind to wander and my body to operate on autopilot. Rather than clicking from one application to another like a zombie, I maintained an interior monologue: Now I’m writing. Now I’m reading this Gawker post. Now I’m browsing through my Twitter feed. I also had to be mindful of my irrational urges to stop working and, say, open my Uber app so I could check my passenger rating. (If I accepted the urge’s existence and continued working, the urge eventually passed. In fact, I still don’t know what my passenger rating is.) This process made me realize how unaccustomed I am to delayed digital gratification. Usually, when I want to check Slack, I check Slack. During the Week of Monotasking, I had to finish whatever I was doing before I checked Slack. It made me feel virtuous, but it also sapped my emotional energy. By the end of the first day I was exhausted.

After a few days of practice I found myself becoming more productive. About halfway through the Week of Monotasking, I looked up from my computer at 9 p.m. to realize that the office was dark, and I was one of two people still there. I’d been focusing so hard, I hadn’t even noticed the time passing. I credit this unprecedented moment to a few tricks I’d implemented to prevent distraction. Most of these tricks will probably strike you as obvious, because they are obvious. (I’m actually a little embarrassed that I wasn’t doing them already.) But in the event that you’ve been as mindlessly distractible as I am, you might find them helpful.

My first trick: Only have one program open at a time. It turns out my two-screen setup has been hindering my ability to get stuff done, because it’s very difficult to focus on one window when you have more than one window open on your computer screen. Once I started minimizing—or, better yet, quitting—the applications I wasn’t using, I found it much easier to focus on the task at hand.

My second tip: Turn off notifications. If you need to leave your email or Slack open during the day to prove to your co-workers that you’re still alive, don’t let them ping you constantly. One of the best things I did for my productivity was to change my notification settings in Slack so that a little red dot wouldn’t appear over the Slack icon whenever there were unread messages in the channels I belonged to. I’ve been conditioned to click on that little red dot, and when it’s not there, I no longer feel the itch to click on it. Of course, you might not be able to disable all notifications, and to a certain extent you’ll have to train yourself to delay the gratification of clicking on notifications if you want to stay focused. But why expose yourself to more temptation than necessary?

The third trick requires a bit more setup: I installed a Chrome extension called Strict Workflow, which enforces a productivity method called the Pomodoro technique, in which you spend 25 minutes focusing exclusively on work, followed by a five-minute break. Repeat the cycle a few times, then take a longer break. When you click on the Strict Workflow icon in your Chrome window, it starts counting down from 25 minutes, and during that period of time it blocks social media sites and other websites that you’ve deemed distracting. For me, the blocking function of Strict Workflow was less helpful than the timer: I found it easier to focus on work when I knew I could take a break in 18, then 11, then 3 minutes. (The extension also times your breaks, so that you know when it’s time to get back to work.)

As much as these tricks helped me focus when I was trying to write or edit, they didn’t convince me that monotasking is fully compatible with modern work. Much of my job requires me to switch back and forth between quick responses and sustained focus: I carefully edit a blog post a writer has filed to me, I send a couple of questions to the writer on Slack or email, then I incorporate the answers and reread the story. To some extent, I’m at the mercy of the pace of communications set by my co-workers and associates, and I have to be available to respond when they need me to (and vice versa). This whole internet communication thing doesn’t work if we all decide we’ll log into chat and email only when it suits us.

“We’re in this environment in the workplace where it’s a structure that’s set up by the technology that makes it really difficult for people to monotask,” said Gloria Mark, professor of informatics at the University of California–Irvine who studies distraction in the workplace. “You can, of course, turn off technology and focus, but then individuals who do that are penalized because they’re not available for interacting with colleagues, they’re not available if their manager needs to contact them, so they’re stuck between a rock and a hard place.”

Mark says organizations can make systemic changes that help employees focus. “If an organization, for example, ends up batching email, and so people know that email is only going to be sent out once a morning, and once after lunch, maybe at the end of the day, then people’s expectations are going to change,” she said. In one study, Mark and her colleagues cut off a group of 13 colleagues from email for a week. They found that the participants multitasked less, felt much less stressed, and spent more time talking face to face (which they reported enjoying).

Even when I wasn’t emailing and Slacking during my Week of Monotasking, I sometimes found that I was technically doing multiple things at once. I would open my Mac’s thesaurus to find the right word, switch from Word to Chrome so I could check a fact, toggle between two research papers I’d downloaded to compare their data, even shift from writing one section of the article I was working on to writing another section when a good idea struck. I wouldn’t describe myself as distracted in these moments, but they made me realize that synthesizing information—which is crucial for most knowledge workers—isn’t simple enough to qualify as a single task. Even good, focused, undistracted work is almost never linear.

My Week of Monotasking ended on Friday, and I admit I was excited to resume multitasking on the day the Euro Cup kicked off. (Watching daytime soccer is where my two-screen setup really comes in handy.) But after a week of focusing, I discovered that doing two things at once wasn’t nearly as much fun as I remembered. Because I was writing emails, participating in Slack conversations, and doing research during most of the game, I couldn’t enjoy the tension that built up as the French and Romanian players passed and intercepted and attacked in midfield. I turned my attention fully to the match whenever someone took a shot on goal, but I was barely getting more out of the game than I would have from a video recap. Even worse, trying to pay attention to multiple things at once made me feel frazzled, pulled in multiple directions, stressed out. I probably would have gotten the same amount done if I’d watched the game without distraction, then written all those emails and read those reports. (Whether my boss would have been cool with that is a different question.)

Does this mean I’m going to stop multitasking completely? No chance. (Full disclosure: I wrote part of this article while keeping an eye on the Belgium-Italy matchup.) But I am going to start asking myself whether I really need to pick up my phone in the middle of a meeting or check my Gmail while I’m reading a Wikipedia page for research. And I will definitely continue using the Strict Workflow extension to limit my application-toggling to short breaks, instead of allowing it to take over my workday. It may not be possible to do exactly one thing at a time in the modern office, but I’m convinced that the fewer things you’re trying to do at once, the better.

Need career advice? Got a problem at work? Email theladder@slate.com.