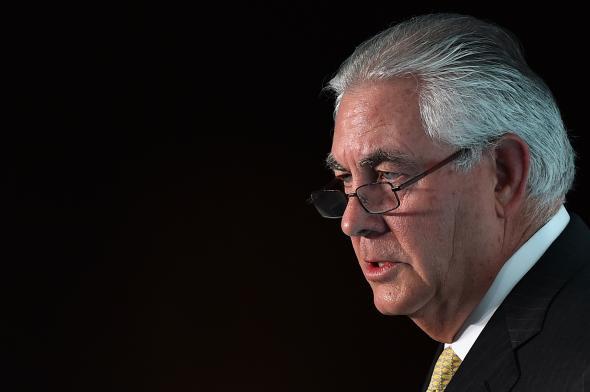

It has become increasingly clear that President-elect Donald Trump plans to place America’s policymaking apparatus in the hands of a gang of old, white dealmakers. The latest apparent winner of The Cabinet Apprentice is in keeping with this vision: Trump is reportedly poised to nominate Exxon Mobil Chairman and CEO Rex Tillerson as his secretary of state.

Unlike so much of what Trump says, the idea of giving America’s top foreign-policy post to the chief executive officer of a global corporation isn’t absurd on its face. The typical CEO of a multinational has far more experience dealing with foreign governments than the typical senator. Many large companies effectively have their own foreign policies, since they do business around the world. And none has one more so than Exxon Mobil, a “corporate oil sovereign,” in the words of Steve Coll, who wrote the book on the company.

There are obvious reasons to be skeptical of a Tillerson State Department—and a few glimmers of a silver lining to his nomination. Set aside the obvious mantra that critics will sound: Government is not business. Tillerson, a native Texan who joined Exxon in 1975, hasn’t expressed much interest in subjects outside the oil business. He and his company are concerned with other countries only to the degree they have hydrocarbons on their land or off their shores that can be exploited. (Venezuela, yes; Guatemala, no. Saudi Arabia, yes; Lebanon, no.) That’s a skewed lens through which to view the world. When Tillerson and his colleagues interact directly with a foreign government’s leader, the conversation revolves around resources and money—not human rights, broad-based economic development, regional stability, or international alliances.

What’s more, Exxon Mobil’s foreign policies don’t necessarily align with those of the United States. Tillerson is tight with Vladimir Putin, in part because Russia is such a significant player in the global resources industry. I can’t imagine he really cares too much about Russia’s annexation of the Crimea. Nor can I see his State Department rallying opposition to a Russian effort to exert its influence in the Baltics. Russia has oil and natural gas; Lithuania and Estonia don’t. Typically, we expect our secretaries of state to give hope to proponents of democracy wherever they can be found and stand up forthrightly for American values and interests. Nothing in Tillerson’s career suggests he would be capable of—or interested in—doing so.

The reality is that the company Tillerson runs, while based in Irving, Texas, is increasingly a rootless, cosmopolitan citizen of no country.* While the U.S. isn’t quite a rump operation for Exxon Mobil, it’s an increasingly less important one. The company broadly divides its businesses into three categories: upstream (getting oil and natural gas out of the ground); downstream (refining, distilling, and distributing it); and chemicals. In the third quarter of this year, Exxon Mobil lost $1.8 billion on its U.S. upstream operations, while earning $2.7 billion on its upstream operations everywhere else. It made $824 million on its U.S. downstream operations, while earning $2.1 billion on its non-U.S. downstream operations. And the U.S. chemicals business made $1.5 billion in profits, compared with $2.2 billion for the non-U.S. chemicals business.

Moreover, virtually all of Exxon Mobil’s future investments are slated to take place outside the U.S. A deck it shares with investors, which you can see here, lists the company’s major projects for the decade. Between 2012 and 2015, of 22 major projects initiated, only two were in the United States. The rest were in places like Canada, Malaysia, Nigeria, Norway, and Russia. Of 37 projects the company anticipates initiating between 2016 and 2018, only six are in the U.S. And they’re generally small, dwarfed by the projects it has planned in Australia, the United Arab Emirates, and elsewhere. America First? Not for Exxon Mobil.

And yet: This corporate internationalism may not be such a bad thing in this case, because it at least means Exxon Mobil doesn’t fully buy into the know-nothing nationalism that the GOP has embraced. To be clear, Exxon Mobil is unabashedly in the fossil-fuel business, which emits carbon. It’s not trying to pivot by getting into solar and wind, as some foreign oil-based companies have done. And it is certainly no friend of the planet.

But precisely because Exxon Mobil has its own foreign policy, it has to respect international norms. Which means Tillerson’s company has taken a set of attitudes and policy oppositions at odds with those of Trump and the Republican Party.

Exxon Mobil has no interest in obviating the need for fossil fuels. But it is taking steps to eliminate emissions from its own activities. Exxon Mobil’s investor slide deck highlights how it has reduced greenhouse gas emissions in its operations, largely through reducing the practice of flaring while stressing energy efficiency and cogeneration (using heat generated during operations to create electricity). The company boasts that is “participating in one third of the world’s carbon capture and sequestration capacity.”

Last month, Exxon Mobil endorsed the Paris climate treaty (which Trump is threatening to rip up). After the election, Suzanne McCarron, vice president of government and public affairs at the company, tweeted a reaffirmation of the company’s recognition of the importance of the Paris treaty and the risks of climate change. The company has also supported a tax on carbon.

None of this is because Exxon Mobil is going green or is being responsive to critics, which include (historical irony alert!) the Rockefeller Family Fund. It is simply because this engineering-, science-, and project-based culture has to be practical and realistic. And the reality of the world is that there are significant geographies in which the company operates where carbon emissions are constrained (like Europe and Canada), and there are significant geographies where they could be in the future (like China.) So it can’t simply stubbornly dig in its heels, the way American coal companies have. Exxon Mobil operates in a global framework, not a domestic one.

There’s no guarantee Tillerson would bring this mindset to the Trump administration. But his background is an indicator of just how strange the next several years are going to be. A friend of Vladimir Putin who has made his life’s work extracting oil from the Earth’s surface could be our next chief diplomat. On a relative basis, he’s likely to be one who recognizes international norms and acts as a force for practicality in the conduct of foreign affairs. But that won’t make his presence in the State Department any less surreal.

*Correction, Dec. 12, 2016: This article originally misstated that Exxon Mobil is based in Houston. Its headquarters are in Irving, Texas. (Return.)