Green, energy-saving technologies are essentially luxury products. Solar rigs and energy-efficiency upgrades require big upfront investments in equipment that may not pay off for many years. Spend $40,000 on solar panels for your roof, and you won’t get your money back in lower electricity bills for a dozen years or more. You’d have to drive a hybrid car tens of thousands of miles to recapture the extra costs in the form of lower spending on gasoline. As a result, going green has historically only been an option to those who can afford to make conspicuous displays of virtuous consumption—not the 1 percent, perhaps, but certainly the top 25 percent.

But that’s changing, in part because the price of solar panels has plummeted significantly in recent years. And in part because smart companies are developing new business models that appeal to the rest of us.

Take PosiGen, a 4-year-old company based in New Orleans that pairs energy-efficiency upgrades with solar-panel leases—all for no money down and monthly payments of $50 or $60. PosiGen doesn’t target yuppies in Boulder, Colorado. A survey covering one-third of its 6,000-odd customers found that “our average customer is a 56-65-year-old African-American female, who spends at least four hours a week at church,” said Aaron Dirks, the intense 40-year-old West Point grad who founded the company. Three-quarters of its installations have been in census tracts where the area median income is below 120 percent of the national median. Call it blue-collar green.

Born in Baton Rouge, Louisiana, Dirks studied environmental engineering at West Point, spent 10 years in the military, and then worked in civil engineering and finance in Louisiana. When renovating his home in New Orleans, he grew frustrated with the paperwork associated with grants and tax credits for renewable energy and efficiency—and with the high cost. Dirks recognized a paradox. “Only people like me were able to get the benefit of something that I should be the last one to get,” he said. Meanwhile, many New Orleans residents with fixed or lower incomes were living in older homes, which are leaky and more difficult to maintain. The result: “They’re the ones paying the most for electricity costs as a percentage of their income,” Dirks says.

Leasing panels to homeowners instead of selling them is one way of reducing the cost of solar adoption. In one popular model, homeowners pay a fixed fee per month and receive the electricity the panels produce for free. (A third party owns the panels and receives the federal and any state tax credits associated with ownership.) When the system makes more juice than the house consumes, in many states, including Louisiana, the electricity is sold to the utility. And at night, or during the summer air-conditioning season, when the home system can’t carry the load on its own, the homeowner buys excess electricity from the utility. And voilà: lower energy costs with little upfront costs. Companies like SolarCity and Vivint have prospered with this strategy but have done so largely by targeting middle- and especially upper-income customers.

Dirks reasoned that pairing a new generating source that reduces the need to buy electricity with home improvements that reduce the need to use electricity would amplify the savings. Here, too, Dirks saw a way to offer this to customers with no money down. In 2010, there were still post-Katrina funds available to pay for weatherization and other home improvements. So Dirks and co-founder Tom Neyhart, started a company, borrowed money from a bank, and set out to prove the concept on about 200 homes. When they enlisted customers, they offered to lease solar panel systems. At the same time, they paid contractors to perform blower door tests, in which workers rig up a fan to highlight how airtight a house is and then do the work necessary to reduce energy leaks. (I had a blower test done on my home in Connecticut for a series on home efficiency back in 2010.)

The goal wasn’t to eliminate electricity bills but to reduce them. “The mandate we placed on ourselves is that our families get a minimum of $50 a month into their coffers,” Dirks says. That is to say, someone who had a $150 monthly bill before the system and efficiency upgrades would see their total combined spending on the solar lease and utility-produced electricity fall to about $100 per month. As the company proved its methods and prices fell, the cost to consumers has fallen, too. Today, PosiGen charges about $50 per month for a 10-year solar lease, and $10 a month for the energy-efficiency upgrades.

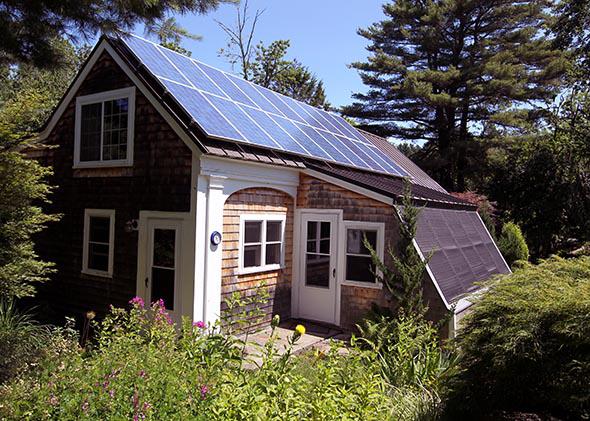

Margie Vicknair Pray, 62, who retired from her job in oil and gas safety in Houston, lives in a 1,000-square-foot home on a half-acre in Lacombe, Louisiana, north of Lake Ponchartrain. In the summer, her electricity bills ran between $185 and $250. The bills were even higher in the winter—up to $300—because her heating system is powered by electricity. After she signed up with PosiGen in late 2013, workers sealed ducts, built a new box on top of her air conditioner, and installed an aluminum tent that zips up to seal off the attic. Then they put 24 solar panels on the roof.

Pray says her savings have been significant. In addition to the $60 monthly payments, she notes that “electricity billing for the summer was as low as $11.” In the winter, the most she paid was $85. Pray estimates that she saved about $1,000 over the course of 2014. “For the first six months, I was posting my electricity bills online,” she told me.

Pray, who owns a small home and lacks the capacity and desire to take on significant financial liabilities, is typical of PosiGen’s customer base, Dirks said. Accordingly, the company doesn’t always require potential customers to undergo credit checks. “What we’re validating now is that people will pay their solar bill before they pay the credit card bill,” he said. If customers default on the lease, the panels come down. While PosiGen didn’t provide specifics, Dirks said the default rate is “very low.”

PosiGen has 150 direct employees and provides consistent employment for another 150 contractors who put up the panels and perform the efficiency audits and upgrades. It has grown largely by bootstrapping and scrounging up credit, and installed its 5,000th system in Louisiana in November. Last fall, PosiGen sealed deals for $40 million in financing from Goldman Sachs’ Urban Investment Group and other investors, which will help it expand.

As it looks beyond the bayous, PosiGen is trying to prove that solar is not just for McMansions with Teslas parked in the driveway. “We look for older housing stock, not a lot of trees, and low to moderate census tracts,” Dirks told me. When PosiGen last year expanded to New York and Connecticut, it opened offices in Albany and Bridgeport, not Scarsdale and Greenwich.

Solar panels may not have the capacity to save the planet. They do have the capacity to put money into the hands of working-class homeowners.