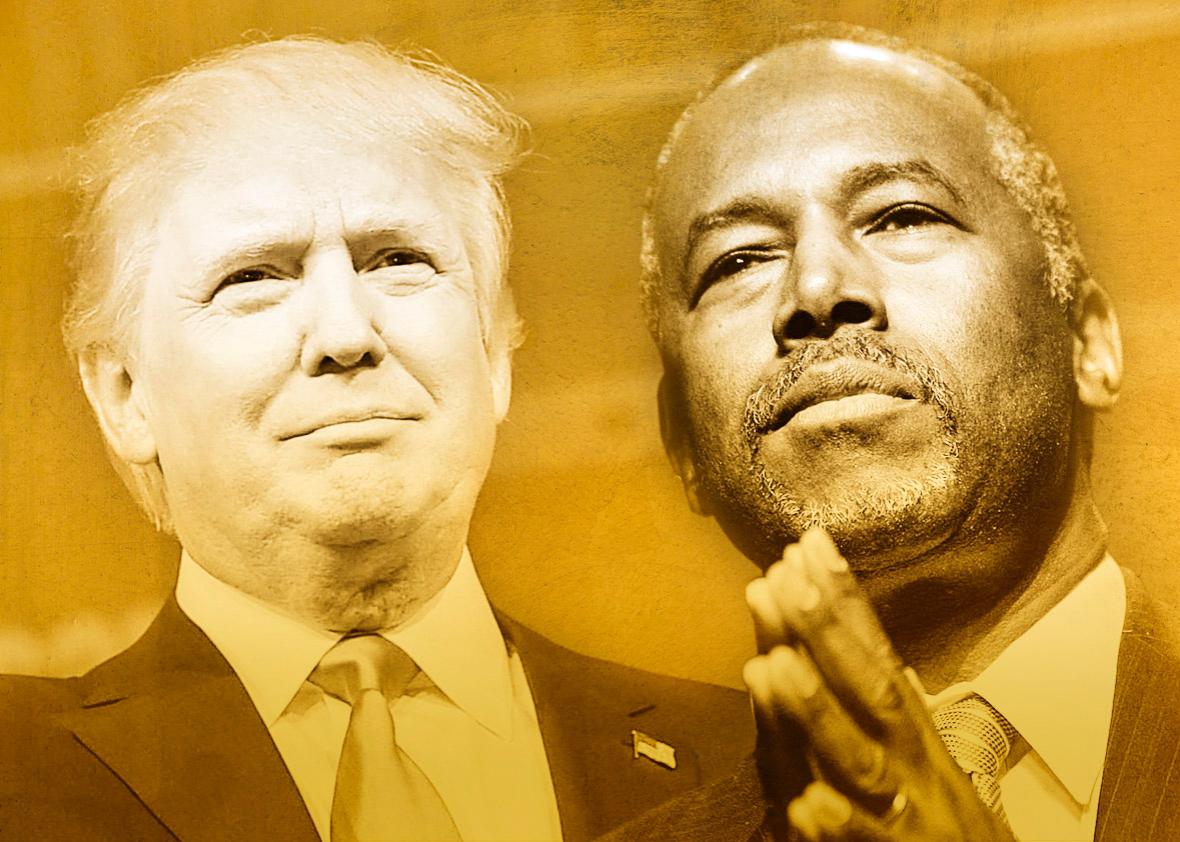

Much has been made of the fact that the two leading contenders in the Republican presidential primary, Donald Trump and Ben Carson, lack any experience in elected office. Much less attention has gone to something else the two men share: a history of entanglements with companies that have been rightly criticized for hawking get-rich-quick schemes to the broke and desperate. The business model, which is perfectly legal, is called multilevel marketing.

In his classic tome of the prosperity gospel movement, Think and Grow Rich, Napoleon Hill told his readers that making money was simply a matter of the right attitude. If you think hard on it, if you want it bad enough, wealth will happen to you. Hill more or less left it at that. Multilevel marketing, or MLM, gives those believers a seemingly concrete plan. Sell our goods and untold wealth will be yours!

Check the website of ACN, the multilevel marketing company that Donald Trump featured not once but twice on Celebrity Apprentice. “ACN has enabled countless people of all ages, cultures and backgrounds to experience financial and personal freedom, allowing them to live the life they’ve always imagined—a life without boundaries,” the site claims.

Then there was Trump Network, Trump’s own multilevel marketing concern, which the Donald bought and renamed after himself in 2009 and sold off for an undisclosed sum in 2012. He described the company as a “rescue and recovery program” for recession-wary Americans.

And let’s not forget Mannatech, the vitamin company Carson’s been saying kind words about since 2004, as the Wall Street Journal reminded us last week. He credits the company’s products with helping him in his battle against prostate cancer. Mannaech offers recruits “unlimited earning potential,” as it terms it in a come-on pitch.

Sounds great. What could go wrong? As the Donald might put, “Watch, listen and learn.”

Products sold through the multilevel marketing model aren’t sold in stores. Instead individuals purchase a startup kit (always encouraged, but not always required) and then contract with the company for the right to sell the merchandise to other individuals. They receive a commission on each sale but are not actually employed by the company. So far, so familiar. That’s the classic Avon Lady model.

But selling goods one by one to your neighbors and friends isn’t the way to riches, no matter how much you hound them or otherwise guilt-trip them into making purchases. So multilevel marketing companies incentivize their salespeople to recruit other salespeople, promising them a cut of all that person’s sales, as long as both the original seller and the new recruit remain active.

Still following me?

Next, the newly recruited salesperson is supposed to go on to bring even more people on board, with money from everyone’s sales flowing upward. Eventually, the pitch goes, a successful salesperson will have dozens or hundreds or even thousands of people working under him or her, while collecting a percentage from their sales.

There’s an oft-told joke about MLMs in Utah, where they’re quite popular: It stands for Mormons Losing Money.

You can think of multilevel marketing as an exaggerated microcosm of the age of inequality. There are a handful of people on top actually making the promised six-figure (and possibly larger) incomes. Mannatech, for example, issued a press release this summer lauding the 200th sales associate over the life of the company to earn $1 million from sales of the company’s products. On the other hand, the Wall Street Journal reported that the average active Mannatech sales associate was earning less than $1,000 annually.

It’s likely not much better at other companies. The Direct Selling Association, the lobbying arm of the multilevel marketing industry, claims 18.2 million Americans—about 5 percent of the population—were “involved” in direct selling last year, generating $34.5 billion in sales. That number sounds terrifically impressive until you realize it equals less than $2,000 per person. Even for work that isn’t necessarily full time, this isn’t exactly raking it in. And the typical seller likely took home even less than that.

Much in the same way that Uber downplays everything from the cost of vehicle wear and tear to the cost of gas when promoting the benefits of signing on as a driver, MLM recruiters eager to sign up fresh sales troops often downplay or explain away fees associated with the business model. While buying the product isn’t required, it’s not exactly discouraged—Mannatech, for example, tells its sellers they can buy the product at a wholesale price and then sell it for the retail markup to their customers. And there are startup costs. ACN, for example, charges a $499 initiation fee and then encourages its newly minted salespeople to purchase such things as a $39.99-a-month program offering office support services. Recruiters frequently seek to rationalize those charges. “The $499 is a small price to pay for a business,” one wrote on an online board. But it’s also about a year’s earnings for a typical recruit: In 2010, the Globe and Mail reported that the average ACN salesperson earned $41 a month in commissions.

On top of all of this, the multilevel marketing industry is a political powerhouse, beating back attempts by the Federal Trade Commission to require it to provide proof of earnings claims to potential recruits. One result? According to a paper published by long-time industry critics Douglas Brooks, Robert Fitzpatrick, and Bruce Craig, who parsed publicly available data from multilevel marketing giants Herbalife, Nu Skin, and Amway, more than 90 percent of those who seek to supplement their income by participating in such businesses actually lose money. They found the average distributor spent more money buying goods from the company he signed up with than he earned in income. (In turn, the multilevel marketing industry says, without actually referring to this study, that some of their recruits simply sign up to get discounts on their own purchases.)

It’s not exactly hard to find people who claim to have had less-than-savory experiences. The Internet abounds with critics accusing it of being a legal “scam.” And on consumer forums, purported former ACN sellers like this anonymous one allege they were convinced to join up by a trusted family member, only to discover they were expected to attempt to convince all their friends to sign up too: “The first thing a recruiter will tell you is to make a list of all the people you know and start inviting them (obviously if you know people with money, much better) and if they refuse, to keep bugging them till they come.”

There’s most certainly one person who has earned a life of financial freedom from ACN, though he didn’t need the money: Donald Trump. He told the Wall Street Journal he received $2.5 million for one speech at an ACN event in 2008; the Journal also reported he’s made numerous other appearances at company sales conventions over the years, including receiving more than $1.3 million in total for three recent company-sponsored talks.

Carson’s behavior has been less egregious. Most of the money he would have received for speaking at Mannatech events went to charity, save for a $42,000 fee in 2013. In addition, he appears to have refrained from actually extolling Mannatech as a business opportunity. Then again, he is talking up the products of a firm that paid millions of dollars to Texas in one of those settlements where no one admits fault, the result of a state lawsuit in which authorities asserted the company was “encouraging” salespeople to claim its products and potions could do things like cure AIDS.

And he’s a doctor. Words fail.

There’s one other thing that needs to be pointed out: Even a legal multilevel marketing company can cross into pyramid-scheme territory if its business is ultimately not selling products to consumers, but primarily selling people on the opportunity to sell products. Unfortunately, this not-so-sweet spot is often all but impossible for laypeople—not to mention government regulators—to locate.

This is the crux of the almost three-year battle hedge funder Bill Ackman has been waging against Herbalife. The well-known short-seller is alleging the company is an illegal pyramid scheme because, as he puts it, “I don’t think very many retail sales are happening at all”—something, needless to say, the company denies. ACN—which Trump once called a “a very big part of the American dream”—has also been accused of pyramid scheme–like practices by authorities in Australia, Canada, and Montana, though in all cases the charges were either ultimately dismissed or settled. In Montana, for example, the state initially claimed the company was making unrealistic earnings promises to convince people to join its sales force, but concluded the recruiters, who were independent contractors and not employed by ACN, were not instructed by the company to make the claims.

As for Trump Network, New York magazine reported in 2011 that recruits practiced how they should respond if someone asked if it was a pyramid scheme. One suggested comeback: “You think Donald Trump would involve himself in a pyramid scheme?”

Of course, common sense would say people realize their chances of achieving millions of dollars in sales via these companies aren’t exactly high. There can’t be that many people who want to buy and sell large amount of vitamins, weight-loss supplements, cellphones, cleaning supplies, energy drinks, and other staples of the MLM business, right? But common sense, never in abundant supply in the best circumstances, all too often flies out the window when people are broke, desperate to get ahead, or simply unhappy with their current work or life situation. And the promises that companies like ACN peddle, sometimes with an extra push from someone like the Donald, can begin to sound pretty good.

So why haven’t the other Republican presidential candidates called Trump and Carson on this stuff? Well, bashing the multilevel marketing business model isn’t good for another business—raising money running for political office. Supporters of Mitt Romney’s presidential runs have included honchos from companies like Amway, Nu Skin, and Xango, yet another health care supplement company. Before Scott Walker withdrew from the 2016 race, Richard DeVos, the co-founder of Amway, along with two other family members, gave $25,000 apiece to Walker’s political organization Our American Revival. They’ve also provided financial support to Jeb Bush’s super PAC, Right to Rise.

And maybe the other candidates see nothing to criticize here. It’s not like economic magical thinking isn’t rewarded in Republican politics. Remember that thing about raising revenue by cutting taxes?